On August 25, 2021, Nazila Toubaei was sitting in a room, watching keywitness Iraj Mesdaghi testify to Swedish judges as part of the criminal trial of Hamid Nouri, which was being broadcast from the court's own CCTV cameras.

As with all other hearings, Nouri was brought into the courtroom handcuffed. He raised his hands, was uncuffed and sat down next to his lawyers. For most of the victims and family members present, this was the only image of Nouri’s face they will have seen.

Not so for Iraj Mesdaghi, whose testimony was crucial to Nouri’s identification and arrest. Now, Mesgaghi recounted his experience – day by day, moment by moment – in the “corridor of death” in Gohardasht Prison, during the 1988 mass execution of political prisoners in Iran, for his role in which Nouri is now standing trial for war crimes and murder.

Nazila, who has been searching for the truth about her brother Siamak Toubaei for more than 30 years, listens attentively for any scrap of information that might help her. Siamak survived the massacre but was later “disappeared” by the intelligence agencies. This report is the second in a series by IranWire following the family’s story to date.

***

"When I saw the teaser trailer for Nima Sarvestani's documentary [about the trial], when I saw Hamid Nouri's face, a kind of nausea filled my chest. Something seemed to be weighing on it. And another thing happened; Nouri's lawyers rightly stopped the trial, twice, because of the chanting outside the court, and because he [Nouri] was insulted and ‘tortured’ by them.

“When he said this, my hair stood on end. Nouri was a torturer… the inmates were beaten with cables and they had to listen to the lamentations of others. I was happy that Nouri was being tried fairly. But on the other hand, I remembered my brother's torture. Again, that feeling… like the trembling of my voice right now; I can’t speak… is something heavy on my chest, which I have no words to describe."

This was just part of what went through Nazila Toubaei’s mind as she was confronted by Hamid Nouri on the TV screen. Today is the second day of evidence against Nouri being given by Iraj Mesdaghi, an Iranian human rights defender and ex-political prisoner.

The prosecutor keeps drawing him back to that ‘corridor of death’, with precise questions on such matters as timings and names. Iraj Mesdaghi has brought a piece of cloth with him. That summer, he explains, there were so many detainees the prisons faced a shortage of blindfolds, so some were given this traditional piece cloth to cover their eyes with on the way to their slaughter.

But through such a scrap of material, the survivors saw everything they needed to. "This isn’t just a piece of cloth,” Nouri told the court. “It’s connected with the hanging of my friends. Those who were taken to be executed were no longer blindfolded. And this was how I came to understand for the first time: the guards who came back from the hall [where prisoners were being hanged] held dozens of these cloths in their hands."

Saturday, August 6, 1988. Iraj Mesdaghi is sitting in the corridor. "Before they took me before the death panel, others had gone before me: Ghasem Seifan, Mostafa Mohammadi Moheb and Mahmoud Zaki, had been executed. Ali Haghverdi was also there. He kept having seizures because in 1983 he’d been kept awake for two weeks, blindfolded. He, too, was taken away.”

The next name Mesdaghi mentions is that of Naser Mansouri, a friend. In June that year, his fellow inmates were told he had committed suicide by jumping from the third floor. But the young Iraj new differently; he’d heard Naser’s name in the corridor, called out by Judge Mohammad Moghiseh, then known as Judge Naserian.

"His spinal cord had been cut, and he couldn’t move. He was hospitalized. Naserian had told a guard, Jasem, to tell others to bring him in. Bayat, a health official, put him on a stretcher. He was taken into the room [where the death panel sat]. He was taken out shortly afterward and down the corridor of death. “I have a picture of his grave. Of the names of the 110 people you’ve seen, I found the graves of 36."

While listing the names, Mesdaghi occasionally pauses as if his throat has become constricted. The next is that of Mohsen Mohammad Bagher, a disabled man who’d played role of a paralyzed child in the 1974 film The Stranger and the Fog by Bahram Beizaei. He was there too, his name was called, and he was taken away either into the mosque or the amphitheater to be hanged, walking on his two metal crutches.

Mesdaghi describes bags full of watches and banknotes collected from the personal effects of some of the dead, which passed into the bloody hands of the Revolutionary Guards. He mentions still more prisoners who left their cells and never returned: "Massoud Ghobari, Ramin Ghasemi, Seyed Hossein Sobhani, Reza Zand, Mehran Hoveida, Asghar Masjedi, Manouchehr Bozorg Bashar.” Then he turns to those names he says were personally called by Hamid Nouri for execution: "Mohsen Mohammad Bagher, Faramarz Farahani, Haidar Sadeghi, Asadollah Tayebi, Mohammad Hassan Khaleghi, Hamid Reza Khatibi, Abdullah Behrangi…

"Every time they were executed, sweets were handed out. Hamid Nouri was distributing sweets. He came to the corridor of death and offered me sweets. Nobody took any. Naserian [Judge Moghiseh] was very happy, and danced in the corridor like a ballerina. Someone asked, ‘When will you take us?’. Naserian danced and said 'I don’t know,' in a sing-song voice.”

Siamak Toubaei: A Believer in Equality From the Very First

Nazila Toubaei has followed all the names. With the one, the image of her brother comes back to mind. Where was he? In those appalling, deadly moments, where was Siamak sitting among the inmates?

We’ve previously written about Siamak Toubaei, who was arrested in September 1981 over his support for the Mojahedin-e Khalq Organization (MEK) while out distributing leaflets aged just 18. He was sentenced to an initial three years in prison, later extended to 10, and was in Gohardasht Prison at the time of the massacre.

Later he was brought home under guard on furlough – but disappeared shortly his arrival. His family suspect this was a staged killing by the Ministry of Intelligence and have lived without knowing his fate for more than 30 years. Nazila hopes the trial will complete the puzzle.

"Yesterday, one of Siamak's fellow inmates told me that my brother always had a smile on his face, and tried to create happiness,” she said. “He said that once, when they took them all and whipped them, the last person to return to the cell was Siamak. When he came in, he said: ‘Guys! I was beaten with pepper; it burns so badly.’ When he said this, everyone laughed, and the guard was so upset because he’d just crushed them but they were still laughing."

She adds: “When you asked me to send you Siamak's childhood photos, childhood memories came back to my mind. As I watched the trial, I remembered the torture Siamak had endured. Siamak had a fit body. It came to me that when he was passing through the Revolutionary Guards’ tunnel, Siamak always stood to the side, so that the weaker inmates would be in the middle and be beaten less."

The picture below shows Siamak, Nazila and Nina Toubaei as children in 1965. All three are wearing their best Nowruz (New Year) clothes. Siamak was two years old at that time; he ran, laughed and played with his sisters in their backyard in the Narmak neighborhood of Tehran, with no idea of the fate that awaited them.

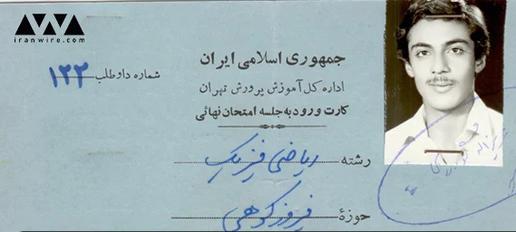

The below is Siamak's identity card for his final exams. He never attended them.

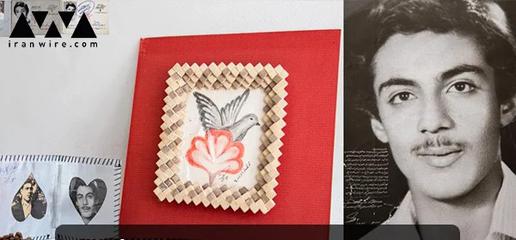

The third picture Nazila shares features handicrafts Siamak made in prison, as New Year’s gifts for his sisters and younger brother Babak. “He made those after 1982,” Nazila says. “On the left is a milk bag for his little brother – he turned the envelope upside down, sewed around it with black thread, and wrote BT on it for Babak Toubaei. The photo was of [Iranian wrestling champ] Gholamreza Takhti. And that painting, he’d drawn on colored paper wrapped around oranges, with a bird flying in the middle; that was mine and Nina's New Year gift."

In late 1979, years before he was taken to prison, the young Nazila asked Siamak why he had joined the MEK "I didn’t have a problem with their ideology; the poorest sections of society support the Mojahedin. Siamak had believed in equality as a child and practiced the socialism he believed in."

Once, when their father returned home from a trip and brought them all souvenirs, he handed Siamak a jacket. Siamak wore it for a day, but then went to school the next day and came back without it. “He told us he’d lost the jacket. But one day when he came home for lunch with a friend who wasn’t well-off, he [the friend] was wearing it. He’d brought his friend over to give him some stationery. He told our mother that he gave the jacet to him. My mother, and most especially my father, were proud of him.”

Siamak's father was a supporter of ex-Prime Minister of Iran Mohammad Mossadegh, and had been arrested and jailed by the Pahlavi government after the coup of 1953. He was held in Shiraz, but later escaped to Tehran and was finally employed by the Ministry of Agriculture.

It took the family a long time, Nazila says, to accept that Siamak had been killed after he came home in October 1989, then disappeared. “Three quarters of me was always looking for Siamak,” she said. “It was as if I was living with a quarter of my brain and soul. It took me years to get out of the denial phase.

“We’d been looking for Siamak for 20 years when I read Iraj Mesdaghi's book, Neither Life, Nor Death, and learned what had happened. I got in touch with Iraj and I think his coming into my life restored my mental health. Think of our family as a piece of paper that's been grabbed and the middle part torn out; the entire page shrinks. Before meeting Iraj, we used to get together with our family but we didn’t talk about Siamak. My daughter Anahita was small then, and once suddenly said in public: ‘Do I not have two uncles? So where is uncle Siamak?’

“My family was angry because I told the child the truth. But it was really anger at not knowing about Siamak, not knowing where he was. Later at a thanksgiving party, my mother recounted a memory of him. My daughter replied: ‘Finally, we’ve reached the point where we’re talking about Uncle Siamak.’ I owe this to Iraj.”

Nazila had read Mesdaghi’s memories of Gohardasht Prison in 2004. It took her another six years to tell her father about it; for years even she had operated on the presumption that Siamak had got back to Camp Ashraf and been killed by the MEK. It was Mesdaghi’s book that finally convinced her Siamak had never left Iran.

“But I still couldn’t accept it,” she said. “I still have so little information about him. I'm still looking for the edges of this puzzle; I want to complete it. I’ve read many prison memoirs and looked for signs – I even know who exposed him [to the intelligence agents] and where he was arrested. But I didn’t name them. I’m here for personal reasons. I’m looking for Siamak here.”

A Jailed Brother to his Little Sister: “We Must Stand”

When the hearing concludes on August 25, Nazila hugs the plaintiffs’ and witnesses' lawyers in front of the court. She asks them, if they can, to keep searching for the other people who went missing that decade, as well as those killed in 1988. Of one, she said, “I felt tears in his eyes as well. He controlled himself and said: ‘I promise I will.’”

Nazila still has the last letter that her brother Siamak wrote to her from prison, dated July 23, 1989. “Now let us talk about the future,” Siamak writes. “The future will be beautiful for all of us. But beauty, good and success are not simple to achieve. You have to strive for it, and face the difficulties. Perhaps in the quest to reach this goal, our movement will be interrupted or retreat. This doesn’t mean the path is wrong and it shouldn’t discourage us. Belts must be tightened, and determination must be polished, and we must stand." It ends, three times over, with the words: “I love you.”

Related coverage:

Hamid Nouri's Trial: Where Is Siamak Toubaei?

Hamid Nouri Trial Opens in Stockholm

'The Nation is a Plaintiff': Scores of Iranians to Testify in Case Against Hamid Nouri

Hamid Nouri to Face Trial for War Crimes in Sweden Over 1988 Massacre of Iranian Prisoners

Iranian Ex-Prisoners Recall 'Courier of Death' Hamid Nouri Ahead of Sweden Trial

Justice at Last? 1988 Massacre Suspect Arrested in Sweden

A Move For Justice Around the World

Raisi's Crimes Against Humanity Will Haunt his Presidency

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments