In an interview this February, the former MP and daughter of the last president of Iran, Faezeh Rafsanjani, observed: “We look at things that have nothing to do with politics or security through the lens of national security.”

Rafsanjani’s diagnosis goes to the heart of one of the most severe and deadly imbalances in the contemporary governance of Iran. Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic 41 years ago, the regime has repeatedly justified crimes against its own people, media suppression and collapses in responsible governance – most recently in its botched response to the COVID-19 pandemic – on the thin pretext of national security.

How and why this became the case, and its human cost down the decades, are the subject of a new report published today by the UK-registered charity the Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and the worldwide NGO, Minority Rights Group International: entitled In the Name of Security.

“The national security imperative has driven the Iranian government to turn on many of its own people,” concludes the author, Drewery Dyke, “committing grave and widespread human rights violations in the name of security and combating terrorism.

“The national security challenge faced by the government is real. Its response to that challenge, however, is conducted at the expense of the human rights of the Iranian people.”

The report calls on the Iranian regime to allow the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on human rights in Iran into the country for monitoring visits – and on the UN to renew the mandate for this role. Its author warns that without intervention, Iran could be pitched into a “human rights emergency” – and in fact, given the severity of the crackdown on the November 2019 demonstrations, this may already be happening.

The Securitization of Iranian Public Life

Drewery Dyke is chairperson of the London-based Rights Realization Centre and a former researcher for Amnesty International. In an interview with IranWire, he stresses that the “national security imperative” has been written into the DNA of the Islamic Republic since the beginning.

“This is an entity that came into existence under threat,” he says, “and was built on a strong national security apparatus.”

From the outset of the 20th Century Iran faced and continues to face many real existential threats: from the attempted carve-up of the country by Britain and the USSR to the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, to the presence of armed groups in Iran’s border regions and the cross-border drugs trade. These are acknowledged threats to Iranian security that require a response from authorities.

But since 1979, Dyke notes in the report, “security considerations have had a pervasive influence on many institutions and policies of the Islamic Republic, epitomized by the growth in power of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC). This has led to what could be called a securitization of governance, and it has had a far-reaching impact on human rights.”

The IRGC was created to safeguard the principles of the Islamic Revolution. Now this unaccountable body – which had 150,000 people under its direct command in 2017, as well as another 300,000 in the Basij Organization, before the dozens of entities and billions of dollars’ worth of contracts under its indirect control – has influence over all aspects of economic and public life in Iran, meaning apolitical issues come to be “securitized” and the IRGC can bypass the government of the day to implement the rule of law as it sees fit.

The term “national security”, Dyke tells IranWire, has been “cheapened” to such a degree in Iran that it can be stretched to legitimize the most wanton of human rights abuses. This pattern is visible in other countries, from Libya to Kuwait. “Iran is not alone in the use of what amounts to ‘national security provisions’ in this way,” Dyke says. “But in terms of the scope and applicability of the provisions, it is a leader.”

Vagaries in Iranian Law

Iran is a signatory of several international agreements on human rights, including the four Geneva Conventions, the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and the International Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. These place a legal obligation on the country to uphold international human rights laws.

Article 19 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic states that “All people of Iran, whatever the ethnic group or tribe to which they belong, enjoy equal rights; and colour, race, language, and the like, do not bestow any privilege”, while Article 23 stipulates “The investigation of the beliefs of persons is forbidden, and no one may be molested or prosecuted for holding a belief.”

But other articles of the Constitution can be read in such a way that these can be practically thrown out. Article 26 permits the formation of groups and associations but only where they do not violate “the basis of the Islamic Republic”; elsewhere, Shia precepts are accorded legal primacy and Iran is described as Muslim and Shi’a.

The “vaguely worded provisions” of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code, Dyke’s report notes, have allowed for repeated human rights violations in the name of security or counter-terrorism. The crime of Efsad f’el Arz or “corruption on earth”, for instance, renders such imprecise crimes as “felony against the bodily entity of people”, “spreading lies” and “aiding and abetting in corruption and prostitution” punishable by death. The Penal Code also prohibits “acts of propaganda” against the Islamic Republic, “espionage” or “collusion” with foreign states. But because “propaganda”, “espionage” and “collusion” are not defined, they can be interpreted according to the needs of the regime.

The Deadly Consequences of Iran’s National Security Imperative

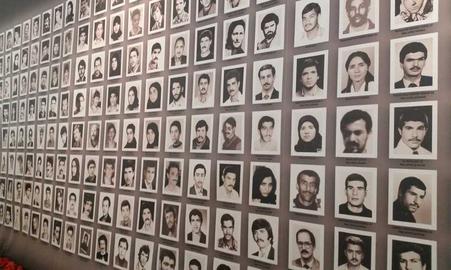

Thousands of people have been executed, tortured and arbitrarily imprisoned in the Islamic Republic in the name of national security. These include political dissidents: most infamously in 1988, when 4,500 to 5,000 political prisoners were killed, but also in the bloody months that followed the Islamic Revolution and amid other periods of unrest, such as during the 2009 Green Movement. Scores of individual activists, journalists and critics of the regime are detained every year on spurious national security grounds.

The maltreatment of religious and ethnic minorities in Iran on the pretext of national security is also highlighted in Dyke’s report. Kurds, Baluchis and Ahwazi Arabs have repeatedly been detained for their claims to cultural autonomy; the incursion of ISIS in the region provided cover for the arrest of hundreds of Ahwazi Arabs. Religious minorities such as Baha’is and Gonabadi Sufis face ongoing persecution for the peaceful expression of their religion. Dyke notes that the discourse and policies of ex-President Ahmadinejad in particular considered non-Persian, non-Shi’a identity a threat to national security.

Dual nationals and visitors to Iran have been arbitrarily detained and some have died in custody, often charged with “espionage” or “cooperating” with hostile governments. In October 2019, Nizar Zakka, a Lebanese IT specialist who was arrested by the IRGC and imprisoned for four years after being invited to the country by its own Vice President for Women’s Affairs, said these detentions had become “a business” for the IRGC: a means of applying political leverage on foreign governments, or extracting huge fines from detainees upon their eventual release.

The report also sheds light on how Iran has effectively engaged in people-trafficking to bolster its extra-territorial security concerns. The IRGC’s Quds Force recruited around 15,000 Afghan nationals – including child soldiers – into the Fatemiyoun Brigade, part of its national defense force in Syria. Among them were undocumented Afghans detained in Iran and coerced into joining as a trade-off for prison sentences, or poor migrant workers promised birth certificates or pay by the IRGC that never materialised. Thousands of these recruits died in Syria.

The self-destructive nature of Iran’s national security imperative has been brought home in recent months. Hundreds were killed by security forces and reportedly 7,000 arrested amid the November 2019 protests, which Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei attributed to “the enemies of Iran”. Then, amid heightened security tensions after the US killing of Ghasem Soleimani, the IRGC accidentally shot down a Ukrainian passenger plane, killing all 176 people on board. People who gathered to commemorate the victims in Iran were suppressed and handed prison and flogging sentences.

Dyke’s report also sheds light on how the national security imperative impacts on the health sector in Iran. Earlier in 2020 state media and the Supreme Leader intimated the novel coronavirus could be a US “bioweapon” and by April, some 3,600 people were reported to have been arrested for “challenging the government’s narrative on the virus in Iran”. Inmates in Iran’s grossly overcrowded prison system were not released on time, if at all, exacerbating an already high risk of contracting COVID-19. “The threat posed by COVID-19 was treated by the Iranian authorities not just as a public health challenge but also as a national security issue,” Dyke writes. “This has had predictable effects.”

National Security or Regime Insecurity?

Securitization has affected all aspects of Iranian public life, both in the political arena and in social and cultural spheres too. As Dyke’s report notes, the Islamic Republic now considers any contact with foreign interests or “any political opposition whatsoever” as a potential threat to national security – rendering life impossible for many people from all walks of life.

“This contract serves to divide people,” Dyke tells IranWire. “It creates mistrust and distrust, engenders conspiracy theories and sows doubt in the minds of individuals who question the motives of others.”

Researchers, journalists, academics and athletes have left Iran in droves over the years, with many citing the repressive political environment. This has hindered the country’s socio-economic development – as, Dyke says, has the IRGC’s monopoly on resources. The Baluchi Sukhtbaran in one of the poorest parts of Iran, he says, smuggle fuel from Iran to Pakistan at great personal risk, out of economic desperation – precisely because the IRGC has taken over local infrastructure, from cement factories to building roads to control of water sources. “The lens of national security has ultimately marginalised and impoverished communities,” he says.

The report calls on the Islamic Republic to adhere to Iran’s obligations under the international human rights treaties it has ratified. Alongside a raft of practices that need to cease immediately, it is also asked to amend its Code of Criminal Procedure to bring it in line with international standards.

“It doesn’t have to be this way,” says Dyke. “They run the risk of escalating national security problems – precisely because of repeatedly drawing on them.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments