Health workers are on the front line of our defense against the coronavirus pandemic – including hundreds of Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. But they are not in Iran; instead, they live in countries around the world, treating their patients, where they are admired and praised by the people and governments of the countries where they live. The one country where they cannot do their work is Iran.

Many of these doctors and nurses – who studied and served in Iran – lost their jobs after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. They were expelled from the universities and their public sector jobs, barred from practicing medicine, jailed and tortured, and a considerable number of them perished on the gallows or in front of firing squads.

The crime of these Baha’i doctors, nurses and other health workers was their faith in a religion that the rulers of the Islamic Republic believe is a “deviant” faith.

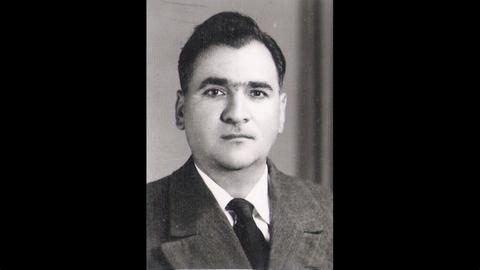

In a new series of articles, called “For the Love of Their Country,” IranWire tells the stories of some of these Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. The following is the story of Dr. Enayat Mazloomi, a dentist and university professor who was expelled from teaching after the Revolution because of his beliefs.

If you know a Baha’i health worker and have a first-hand story of his or her life, let IranWire know.

Many dentists who graduated before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, from Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, remember Dr. Enayat Mazloomi as an elegant, earnest and disciplined man. His classes were always popular.

After years of teaching at the University of Mashhad, and only because of his belief in Baha’i faith, Dr. Enayat Mazloomi was expelled after the Revolution and was harassed by the Islamic revolutionaries. He helped establish the Baha'i Institute for Higher Education after the Revolution – an underground university created because Baha’is were barred from studying – and taught the Baha’i students who were deprived of higher education. Dr. Enayat Mazloomi passed away in 2005 after years of being excluded from formal teaching.

Childhood and Education

Enayat was born to a Baha’i family in January 1937 in Nasrabad, a village around the city of Taft in Yazd province. His grandfather was a Muslim cleric and a prayer leader in the village mosque. He became a Baha’i – but by popular request of the villagers he continued working even after his conversion. His father, Fathollah Mazloomi, was a farmer. When Enayat was two years old his parents moved the family to Tehran. Many clerics were in were in the habit of inciting people to harass and harm Baha'is. This kind of harassment made small cities and villages unsafe for Baha’is. Many Baha’i families with small children moved to bigger cities to protect their children.

Enayat's father opened a dairy shop in the first years of moving to Tehran. He later worked as a painter and decorator and progressed to architecture. Fathollah Mazloomi is known to be one of the first architects who designed homes in the city’s Gisha neighborhood.

Enayat went to Hatef elementary school. His first three years of high school were spent in Parnia, Bisotoon, and Mahyar high schools. He received his diploma from Bamdad high school in Karun Street.

Enayat’s best friend during his school years was Kambiz Sadeghzadeh Milani – who later became a doctor and was abducted by Iranian security forces in July 1980. Dr. Milani remains missing to this day.

After getting his diploma, Enayat prepared for the university entrance exam. He was accepted to study chemistry in Tabriz and dental medicine in Tehran: he chose the latter. He graduated with a doctorate degree from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, in June 1965.

Marriage and Career

Dr. Enayat Mazloomi went to mandatory military service after graduation. His training was in Tehran, during which he married Noranieh Majidi, on March 22, 1956. Dr. Mazloomi was sent to Kerman after six months of training. His wife Noranieh had a degree in English but was working as a microscopist at the Office for Malaria Eradication in Tehran at the time. She was transferred to Kerman as well to be with her husband.

Dr. Mazloomi worked as a non-commissioned officer for a year and a half. He treated patients at the garrison in the mornings and at his private office in the afternoons. Once his military service was over, the young couple, who now had a child, decided to remain in Kerman province where their service was needed rather than to return to Tehran.

Dr. Mazloomi was hired at a clinic in Sirjan. They lived in Sirjan for a year from 1967 to 1968. Dr. Mazloomi was then hired as a teaching assistant in the dental department of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad – so the moved to Mashhad. Dr. Mazloomi was one of the first dentists who joined the faculty of the dentistry at the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

Dental Teaching Career

Dr. Mazloomi became an assistant professor in 1971 and officially joined the faculty of the Ferdowsi University Dental Department.

In March 1972, he became the head of the Education Office of the Dental Department. He was elected as head of Education and Research Operations, head of the Library and Publication Committee, head of the Journal Club in 1974, and as the Secretary of the Faculty Council in 1977.

Dr. Mazloomi spent most of his time teaching. He received a scholarship from Ferdowsi University for a one-year program in tooth anatomy at Dundee University in Scotland in September 1973. He returned to Iran after a year and taught tooth anatomy, oral histology and other related courses in Ferdowsi University.

Dr. Mazloomi’s classes were very popular. He talked about the role of a dentist or a doctor in creating a healthy community as he taught his courses. This was a new topic for many students and rooted in Dr. Mazloomi’s interest and studies in sociology.

The Deputy of Education and Research of the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad asked Dr. Mazloomi to write a book. The first book, titled “Recognizing Teeth Shapes” had already been drafted and the second was in works, on “Tooth Histology,” when the Islamic revolution occurred. The fate of those drafts remains unknown.

“Father’s book was the result of his education,” Kamyar Mazloomi, son of Dr. Mazloomi, told IranWire. “He wrote it between 1979 and 1981 and sent a copy to the person in charge at the university. We don’t know if it was published. It is possible that a draft was in his desk drawer but it was lost when the house was confiscated. The version sent to the university was commented on and edited. There was emphasis on using Persian terms rather than English ones. It was even decided that a thousand copies will be printed for the first publishing run. But then the university curricula were censored and we don’t know what became of the book.”

Dr. Mazloomi received a scholarship from the head of Ferdowsi University to study at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, in the United States, in June 1978. He left Iran for the US in July.

The Islamic Revolution was in full swing by July 1978. Enayat’s trip occurred at the same time as an incident concerning his brother-in-law, Behnam Majidi. The Hojjatieh anti-Baha’i group took advantage of the prevailing chaos and, with the help of local clerics, incited people to loot the homes or businesses of the Bahai’s or to expel them from small cities and villages. Some Baha’is died as well. Majidi’s body was found in a garden in a village around Karaj on July 26, 1978. He was 23 years old and a student of chemistry in Aryamehr University (now known as Sharif University). He was an active member of Baha’i community in the region.

The Revolution, the United States and Returning to Iran

Dr. Mazloomi finished his course in the United States in a year – just a few months since the Islamic Republic had been established. And from the start the Baha’is were under pressure. News of Baha’is being kidnapped and killed was coming from all over the country.

Friends and families asked Dr. Mazloomi to not return to Iran and encouraged him to take his family to the United States before it was too late. He also got a job offer from Georgetown University. But Dr. Mazloomi had made his decision to return. “I have studied here [in Iran] on the Iranian people’s money. I promised to go back and serve my people and my homeland,” he said at the time.

A year after Dr. Mazloomi returned to Iran, the “Council for Filtering and Sanitizing Ferdowsi University” wrote a letter to the university chancellor, on August 30, 1979, saying: “Since Mr Enayat Mazloomi, an academic member of the university, is the subject of filtering and sanitization per documents available to this committee, please place an order to prevent assignment of any official and educational role to him and ask him to refrain from being present at the university.”

This letter put an end to 13 years of sincere work by Dr. Enayat Mazloomi in the Dental Department of Ferdowsi University.

Years of Being Chased and Harassed

Dr. Mazloomi spent most of his time working from his private clinic after being expelled from the university. In August 1981, he took his daughter to Tehran for medical care. Once there, his wife informed him that a few agents had visited his home and his office, looking for him. The Baha’i institutions advised him to not return to Mashhad.

On November 22 and 23, the provincial television network and Khorasan newspaper announced that thirteen Baha’is, including Enayat Mazloomi, were summoned by the Fourth Branch of the Revolutionary Court of Mashhad. That year many arrested Baha’is had been executed by firing squads. Dr Mazloomi’s life in hiding then began. His three daughters, his wife, and two of her brothers filled their car with a few of their belongings and left for Tehran on the evening of November 27, 1981. A few days later, their home in Mashhad was confiscated.

Twenty-six years later, when Enayat had passed away, Noranieh Majidi, Dr. Mazloomi’s widow, went to Mashhad and visited the office of the Deeds and Property Registration. The archive officer showed Noranieh the file for their confiscated property. It said “The court’s order was based on his belief in Baha’i faith.” The order was dated February 20, 1982, and was numbered 3144/107.

Dr. Enayat Mazloomi had no job and lived in hiding for a year. The family had a very little income. Their only source of income was Noranieh’s retirement, which was cut in June 1993, when Enayat and his wife, who were attending a religious meeting were arrested for two days.

Dr. Mazloomi was referred by a dentist friend to a clinic on Karun Street after a year. He worked there under the name Nasrabadi which was the second part of his family name. He used this second part to introduce himself during his life in hiding. He worked in this clinic until the late 1980s and was able to open his own private office in the early 1990s.

In 1986, Dr. Mazloomi was called up to serve in the Iran-Iraq war. He was stationed in Khuzestan as a dentist twice, each time for a month. He was called up again in 1987, this time to the front line.

Kamyar Mazloomi says: “Being called up to serve in the war was the first forced contact he had to have with a governmental organization. He had some peace of mind after that and his life in secret slowly ended. Family visitations and meeting with friends started again around this time. But 21 years after his escape, and two years after my father had passed away, in a phone call with the Fffice of the Execution of Imam Khomeini's Order about his inheritance, they were surprised to hear that my father was living in Iran!”

Finally in August 1991, the Foreign Education Evaluation Commission announced Dr. Enayat Mazloomi as an expert in oral histology and, four months later, on January 8, he was issued a permit for a private office with histology expertise.

Teaching in the Baha'i Institute for Higher Education

The Baha’i community of Iran established the Baha'i Institute for Higher Education (BIHE) in 1987 to teach Baha’i youth who were barred from attending higher education. The BIHE retained the services of professors and teachers who were expelled from the country's schools and universities. Dr. Enayat Mazloomi was among the first professors to join this newly established institute.

One of the first majors taught was dental sciences. Dr. Mazloomi taught different subjects such as removable prostheses and tooth anatomy.

“Dr. Mazloomi was very earnest and disciplined in his classes,” one of his students told IranWire. “The classes were held in the homes of Baha’is but Dr. Mazloomi treated it like a classroom at a university. He was very strict in exams, marking, and evaluating thesis submissions. He believed being strict made the students take the BIHE seriously and work on improving their scientific knowledge.”

This Baha’i student recalls that Dr. Mazloomi talked about his time teaching in Ferdowsi University of Mashhad which made his class more interesting for students and informed them about methods and details of academic education which they did not know because of the ban from universities.

Despite renting laboratories for practical courses and taking lessons in clinics, to make sure the course was current with the universities around the world, Dr. Mazloomi still had concerns. Working as a dentist was not allowed without a permit from the Islamic Republic’s Medical Council.

Dental sciences was removed from the majors taught at the BIHE after a few years. But courses taken by students were accepted at other universities around the world and graduates were able to continue their education.

Death of a dentist who loved teaching

Dr. Enayat Mazloomi, together with ten other members of a Baha’i council, were arrested on September 29, 1998, by officers of the Ministry of Intelligence, who raided classes and homes of Baha’i teachers and students. He was freed after three days.

Kamyar Mazloomi says: “My father was invited to be the technical lead at a clinic in east Tehran in 2005. The reason for inviting him to the job was this: when we looked at the qualifications of dentists in the Medical Council, you were the only person listed with tooth anatomy expertise.”

Dr. Mazloomi accepted the offer and was preparing to start the work when diabetes stopped his heart. He died on the evening of August 15, 2005, after 16 days of being hospitalized in the Tehran Heart Center. He was still debarred from doing what he loved most: teaching in the universities of Iran.

Read other articles in this series:

From Poverty to Medicine to Education

The Doctor With the Unforgettable Smile

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments