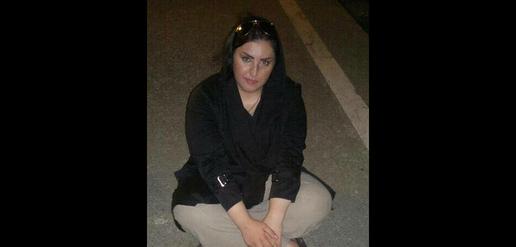

As a lesbian living in Iran, Samira endured humiliation and isolation. Now, she says, it is time for her to make sure no one else has to experience what she did

I was born into a family of “almost” four. I say “almost” because I lost my father when I was nine. It was around that time that I became aware that I liked one of my friends in a different way. We spent many nights and most days together and I really liked her, so much so that I remembered when her family moved out of our neighborhood I was upset for a long time and struggled to overcome my grief.

In those days I was even wondering whether I had done something that caused her to leave me so that I would never see her again.

When I started middle school this kind of feeling towards my classmates became clearer for me. At the time we were allowed to take off our headscarves inside the school and during the day we were more relaxed. For many of the girls my age, adolescence meant spending hours in front of the mirror and trying out a bit of light cosmetics on the face, but for me it was looking at all those beauties without wanting to do it myself.

The best and the sweetest moments were when I sat next to the classroom’s window and watched the hair of my classmates blowing in the wind.

At long last I fell in love with one of them. I could not be away from her and watched over her constantly. I was so mad about her that I told her I wanted our relationship to be more than what it was. To be honest I had no idea what it was that I wanted exactly but I knew that I wanted something more. But with this confession something happened that I had not foreseen, something that would change my entire life. She quickly informed school officials of what I had told her and they told my mother.

The outcome was that I was expelled from school. They let me back in after two weeks, but the circumstances had changed.

During those two weeks my mother was taken ill and was hospitalized. My uncle, who had become our family’s guardian after my father died, got wind of the story and subjected me to all kinds of restrictions. He would not let me go anywhere or talk to anybody. I was under strict control.

But this was just the beginning. When I returned to school an unwritten law was put into effect over and over again. The law was that I was different from others. I had to sit at a desk all by myself. I was not allowed to do teamwork and every look I got gave the message “how disgusting you are!”

Days passed and this became my daily routine until I finished high school. For almost six years, school was a torture chamber for me, full of humiliation and isolation. But home was safer. My mother was an educated woman and she had done some research on homosexuality. Perhaps she did not show it explicitly that she loved me the way I was or that she had accepted my sexual orientation but she made the point that “this is your own life.” This was an indescribable source of serenity for me. And in practice I witnessed that for her I was still the same Samira, and that nothing had changed.

My mother died of an illness when I was 17 and, against my wishes, I was sent to my uncle’s home to live there because he was now my sole guardian. Living in the home of somebody who even before the death of my mother issued dos and don’ts to my brother and I was not easy for me. My brother easily adapted to the situation but for me even the little freedoms that I had enjoyed before at my home were replaced by daily insults. For example, I could not participate in family parties. I was not allowed to sit at the family dinner table because they believed that my presence would take away the blessing. I could not even attend my brother’s wedding ceremony. This isolation, and the acute fear of a forced marriage in a family where girls were married off when they were 22 or 23, was always with me.

Nobody to Say Goodbye To

I was repeatedly told, “You caused your mother’s illness and death.” When I left Iran, this was one of the main reasons.

Despite all those pressures, I was able to form a relationship and keep it going for five years. This made the decision to leave Iran even harder. But I left Iran, with all my loneliness, when I was 22. I did not want anybody to get wind of it. For a month, I took my clothes out of the house one by one and stored them at a friend’s. At last I packed a small suitcase and left that house and Iran forever. All by myself. Not even one person was there to bid me farewell.

I got to Turkey. I did not know the language and had no money. In my two years in Turkey I suffered hardships that now I cannot believe I was able to cope with. But at last those two difficult years of my life were over. Only those who have lived in those small Turkish towns seeking asylum would understand what I am talking about. Whatever I say would not accurately describe the conditions. From morning to afternoon I roamed the streets, gathered plastic garbage and then took them to the plastics mill. I cleaned them and made new plastic things—all of it for 20 liras per hour, which was really a pittance, but that was all that I had.

When I was in Turkey, my girlfriend married. We were both aware of our emotions and orientation and her marriage hit me hard. I could not even speak with people, let alone make friends or pour my heart out. or Living the life of the only lesbian in a small, traditional and religious Turkish town had its own difficulties, the least of which was that once in a while they would throw me out of my home with the excuse that “you are a filthy creature and there is no place for you here.”

I suffered all the hardships and the sorrows throughout those two years, hoping for a future when I could prove that I am proud of myself. If my mother were alive she would feel the same way.

I have now been living in Canada for eight months. I am happy and have a definite plan for my future. I have a difficult road ahead and I constantly remind myself that I have had no family, and this might be my weakest point. I am thinking about forming a family of my own. I want to become fluent in English, continue my education and, when I qualify, work for organizations defending LGBT rights. I have suffered a lot to get to the point where I can say “I am.” My wish is that nobody, especially those in Iran, should have to go through what I have been through. My wish is that, after many years of working for this I would hear the words, “We did not experience what you experienced and our families treated us very well.”

I want to see the results of my work and succeed in it so that nobody can say: “Your mother died because of your homosexuality.” I want to be the last person to hear such cruel words.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments

Your mother sounds like a beautiful lady who loved you and cherished you as you are. It is true that no one can take that away from you with their harsh words. The world is full of people that inflict this kind of discrimination out of their ignorance and hate but I'm so honored to know that you continue to work towards a better future for those that may have to face similar circumstances. Your mother would be so proud of you.

Lots of love. ... read more