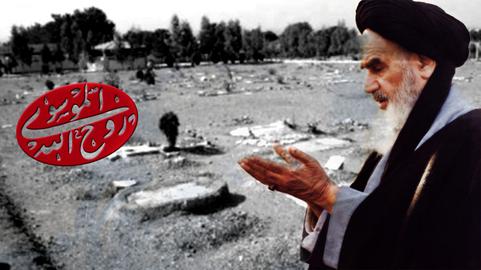

During the summer of 1988, the prisons of revolutionary Iran went from teeming to eerily empty. At the order of Ayatollah Khomeini, authorities executed some 5,000 political prisoners, including women and children, many of whom had been arrested for nothing more than scrawling a slogan on a wall or being in possession of a pamphlet. Guards piled the prisoners onto trucks and either hanged them by beams, in groups, or lined them up before firing squads. The mass killings of that summer, the 25th anniversary of which falls this year, have at no point captured the world's consciousness or provoked global outrage, but for Iranians there is perhaps no darker moment in recent memory.

The truth around the events of 1988 have been the focus of the Iran Tribunal, an independent tribunal set up by families of victims and survivors, which ruled last year in The Hague that the Islamic Republic committed crimes against humanity during that period. While the ruling was mainly symbolic, it followed hearings in London where 100 witnesses gave testimony that evidenced systematic torture and rape in prisons. To better understand the Iran Tribunal's purpose, with its elements of both a war crimes court and a truth and reconciliation commission, we talked to Payam Akhavan, a leading international human rights lawyer, who prosecuted the tribunal. Akhavan discusses the tribunal's most powerful moments, how a nation can grow stronger by coming to terms with its violent past, and the Iranian government's surprising reaction.

The tribunal seems to have arrived at its final judgement. Could you describe where it stands now, and whether there will be any further steps?

The tribunal has completed what it was intended to complete and it is not clear where it will go next. It was held in two phases, one was a truth commission phase held in London in June of last year, and the other was a judicial phase held in the Hague last October to hear the testimony of about 100 witnesses from a broad cross-section of political, ethnic and religious groups and to address the crimes committed by the Islamic Republic of Iran between 1361 and 1367.

What were the tribunal's objectives? How did it come about?

The tribunal itself is the initiative of the families of victims and survivors, largely of leftish political groups. The mothers of Khavaran, [the unmarked mass grave site where political prisoners were buried] were behind this and they asked a group of us who are international lawyers and judges to put together a credible case. They didn’t want a forum for political posturing and slogans. They wanted a credible process that would have a lasting historical effect and unquestionable credibility.

I would see it as an important first step in the process of exposing the Iranian public to the truth of their violent past. The tribunal is certainly an important part of that but I hope not the only initiative.

I would hope that other groups would have similar initiatives and that the whole objective of uncovering the truth – so that we can ensure that the past is no longer repeated in the future – becomes part of our national consciousness. I think that the objective of this process is one both of healing, education and public transformation for every victim of torture, of imprisonment, of unjust imprisonment, of execution. There is a whole circle of others that become affected by the violence.

How do you think the Tribunal has contributed to humanizing and making that violent history more tangible, especially to young people who may have been born after those years?

We can reduce victims to statistics, we can talk about whether 20,000 people were executed during those years or 40,000, but we forget that for every victim there is a name, there is a mother, father, brother and sister, co-worker, school friend, so the effect of this violence is quite widespread in society. And so to understand why we suffer from a culture of abuse and violence in contemporary Iran, we need to go back to the early years of the revolution and understand the DNA of violence. And the impunity and imposed amnesia for those crimes.

When you have a man like Mostafa Pourmohammadi, who is now the minister of justice in Rouhani’s supposedly reformist cabinet, who was involved in the 1988 mass executions, who instead of being prosecuted for crimes against humanity is still 25 years later being promoted to positions of authority, you begin to understand the culture of impunity that rewards rather than punishes violence.

It seems as though the tribunal is meant to be a collective experience, or a stand-in for a collective experience, that Iran needs to have. Do you see it that way?

Looking at the past is about giving victims a catharsis, which is essential for a process of healing, and it also exposes the public to the intimate reality of human rights violations. When a mother comes with the photograph of her four children and she weeps as she talks about their loss, we no longer ask what political or religious orientation her children had. We see simply the grief of a mother who has lost her children. We see the reality of violence free of political slogans and propaganda. It’s sort of a process of humanization and creating a shared space in which we can transcend political, religious and other differences and simply come to the conclusion that the future of Iran has to be built on a culture of human rights and shared values.

Is the tribunal meant to be inclusive process? Have both sides been given a chance to examine their pasts?

I think that the process of exposing and learning from the past is not about vengeance, it’s not about politicizing human rights. It’s really about reclaiming a lost humanity. The question of reclaiming humanity on the part of the victim, for example, isn’t the only objective of justice. I think that one needs also to understand that just as a torture victim has a lost humanity, the torturer also has a lost humanity. That this collective national healing and redemption – moving from a culture of violence to a culture of non-violence – is also about freeing our society from hatred. We forget that even the torturer, the tormentor, is also inflicting great psychological damage on himself.

But as you say, this is a first step, right? There needs to be much more in order to fully address the long trajectory of political violence Iranians have endured after those killings as well.

I think that we need to create a space in which we can have a dialogue about suffering, injustice, healing, reconciliation and justice. And this is really a first step. Eventually in a democratic Iran there must be a properly constituted truth and reconciliation commission, which on behalf of a government with democratic legitimacy would travel throughout the country and hear the testimony of tens of thousands of victims and perpetrators as well. So the point is that until we begin to expose that truth and to talk about it within the right frame of mind, then we don’t even create the space within which we can begin to talk about forgiveness.

Has the Tribunal actually included testimony of perpetrators or participants in the mass killings?

One was a former executioner who came to the tribunal and testified about how he had been responsible for meting out the final bullet to prisoners. He talked about how he had basically been brainwashed as a 16-17 year old in prison to turn against his fellow inmates and to execute them as a demonstration of his repentance. The courage of that man to come before the mothers of the same children he had executed and to see how he was totally destroyed by what he had done, was incredibly powerful. To see how he needed to unload this incredible burden from his soul. One of the most powerful moments was when he said ‘I wish I had also been killed’. He said ‘every morning I wake up I have to remember the look in the eyes of those young prisoners that I shot and I can never forget that image.’

What other powerful moments come to mind?

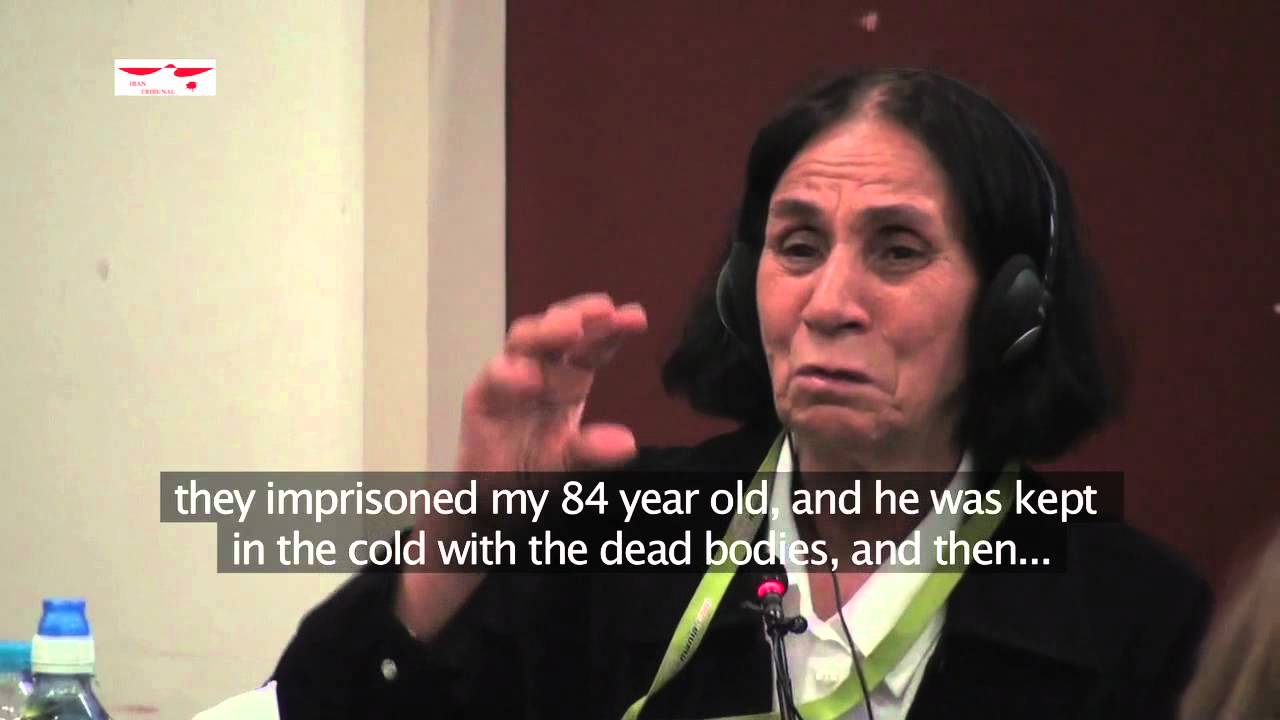

One woman explained how her sister was hanged with her 11-year-old son in Shiraz. Another talked about how a 14- year-old boy who was being hanged together with her husband was crying for his mother and how her husband comforted him during those final moments.

There was also the experiences of a Baha’i woman from Shiraz who was the only member of a group of women in 1983 who was not executed. She the story of a final farewell between a husband and wife, a young newlywed couple, who were about to be executed. And after the testimony I noticed that an elderly gentleman had come up and was talking to her and weeping. And it ended up that this man was a former member of Hojjatieh, who said he had been brainwashed and been responsible for fomenting hatred and violence against Baha’i’s. So it’s a powerful moment when people realize that the violence they were inflicting on others was also violence upon their own humanity.

This all sounds incredible, but what has access been like for people inside Iran? Have they been able to read about the Tribunal or follow its proceedings?

I know that other than the BBC, Voice of America, and the usual media outlets, one of the most significant coverage of the tribunal in addition to live streaming and other means of broadcasting of the hearings was a 20 minute documentary by Manoto Television, which is what the young people watch, and it was very encouraging that young people expressed so much interest in this. So it is very difficult to gauge but I think that millions of Iranians got some glimpse of these tribunal hearings.

Has there been any reaction from the government?

After the conclusion of the tribunal hearings in the Hague, there was an unprecedented, and I would say, astonishing article that basically admitted that in 1988 there was a fatwa ordering the mass execution of political prisoners. The article was suggesting, I think with a propagandistic spin, that Ayatollah Khamenei who was president at the time had done his utmost to save some of the Marxist political prisoners, to spare them. Now this is remarkable because it is an admission that the executions took place and it’s also an admission that they were wrong. Despite the fact that the Imam had issued the fatwa. And thirdly the propagandists obviously feel the necessity of portraying Ayatollah Khamenei as a human rights champion. So that to me was a remarkable gauge of the perceived need on the part of the regime to respond to what they see as anti-regime propaganda. Which to us is simply historical truth. And it’s incredible that once a number of newspapers and other Iranian language media outlets begun to write about this admission, the articles were quickly removed.

Does Iran need to undergo a major political shift before Iranians can begin grappling with this painful past on a more national or collective level?

As I said this is a slow and long term process. We have to imagine in a democratic space in Iran how we can effectively engage in some collective therapy. An entire nation has these deep scars and wounds that need to be healed. For example could we imagine the day when we have a democratically elected president, a woman who maybe today is a political prisoner and torture victim. I’m thinking here about Brazil’s president Dilma Rousseff, who was once upon a time a political prisoner, a torture victim, and it would have been unthinkable that one day she will be president.

Let’s imagine that in the future we have such a president and she walks with a bouquet of flowers to the Khavaran grave site and she apologizes to the mothers of Khavaran for the loss of their children. What effect that would have on the collective consciousness of the Iranian nation? What image of the future would such a leader convey to the Iranian people? What if we were to take Evin prison and turn it into Evin Museum, where people come as they do to Auschwitz, where school children come and see the photographs of the victims, read their stories. A place that becomes part of the public disapproval of torture and that dark past that we need to put behind in order to build a better future.

Do you think our current political culture could accommodate that kind of transformation?

I think that very often we understand power in a narrow political sense – is it this or that faction in power, which factions controls the economy, which controls the security forces. We have to redefine power. Power is not so much the leader that out of fear has to execute and torture in order to maintain authority. But perhaps power is that image of the woman president who apologizes, who has the courage and legitimacy to apologize to create a culture of forgiveness. I often think that if a man beats his wife and children and then silences them when they complain, would we say that that man is powerful? Of course not, that man is pathetic and weak and he cannot even admit his own cowardice to himself. That’s exactly why he need to inflict violence on his wife and children who are weaker than him. So I think in the same way the psychology of a government that needs to rape and torture and imprison and execute its opponents is the psychology of a profound weakness, paranoia and cowardice.

Is there a demand here for everyone to consider their own role in this history?

In a sense we have to assume responsibility for our own past. How is it that we allowed the Islamic Republic to take power in 1979 and inflict such extreme violence? Did we condemn the executions in the early days of the regime or did we condemn them because of our hatred for Baha’is? What was the connection between the initial executions and the escalation to the mass executions in 1361? So these are the kind of processes of learning and reflection that we need to redefine power and create an entirely different context within which to define ourselves.

It's very powerful but difficult to consider questions of accountability in this way. Essentially, you're asking us to consider this long spectrum of response, from condemning outright to silence.

This link is a powerful mini-documentary about the testimony of some victims including this lady, who was called Madar Vatan Parast. Her first name was Esmat, and she is the one who lost virtually her entire family, the one who’s sister was hanged with the 11-year-old. And it’s just really unbelievable to think about how is it possible to lose your brothers and sisters and children and to go on living. Actually the survivors are a source of extraordinary inspiration. And they teach us a lot about the resilience of the human spirit, what it means to be a human being. About the reality of human rights beyond political slogan or intellectual abstraction, so I think we can take even our suffering as a nation and make it into a powerful force for transformation.

Have other nations emerged from these experiences having grown and evolved?

Yes, I’m saying this as someone who spent may years with survivors from the Rwanda genocide and Yugoslavia. I think it’s important for us to have hope and not just to despair about the violence of the past. As you see in that video, there is a second witness, an elderly lady. You can see her grief when she is speaking about the loss of her nephew but also to see the interviews later held in a nice garden. She is sitting in the garden talking about how she has healed, how she is remarkably happy. It’s remarkable to see this incredible relief when this wound that has been eating away at you for years like a cancer, all of a sudden finds a space which it can be shared with others.

Are there other countries in the Middle East or the Islamic World that have had held similar processes? Can the Iran Tribunal be a model for the region?

I recall that in Morocco they had some sort of truth commission process, but then I don’t think Morocco had the same experience in terms of the level of violence that we’ve encountered in Iran. And in Libya they are still in the process of attempts to prosecute some of the former Gaddafi officials, but I would say really Iran could very well lead the way to the Middle East. And the irony is that I was in Egypt in Tahrir Square in 2011 and I talked to people in the streets and it seemed that Egypt was closer to where Iran was 30 years ago rather than where Iran was in 2009. So Iran today Iran is unlikely other places in the Middle East, it's in a post-utopian phase of consciousness.

What makes Iran distinct in that way?

I remember when I worked with the United Nations in Cambodia, one of the Cambodian princes told me that instead of sending his son to study in Paris at the Sorbonne, he sent him to study at the Soviet Union at Moscow State University. When I asked him why, he said ‘I want to make sure that he doesn’t become a communist, so I’ve sent him to the Soviet Union’ . I think this has stuck with me over the years because it’s what we call historically in European history ‘Romantic Ideologies’ whether it’s Marxism or national socialism. These are all romantic ideologies.

Once I gave my students a speech and I had one of them read it. It’s a speech about nobility and heroism and the students were amazed by how powerful it was. And after, I just said that was a speech by Goebbels, Adolf Hitler’s propagandist. The greatest evils in history are always committed in the name of good. No one ever stands up and incites people to violence without appealing to some higher cause. So the point is that our disillusionment with ideology, our cynicism and skepticism toward power in Iran, I would say is far more advanced than it is in other places in the Middle East.

Although 35 years of totalitarianism and national decline, the pain and suffering, is obviously tragic but it can also be a powerful lesson. If we have already paid such a heavy price at least let’s learn from it, or transform it into a kind of national cultural asset. And I’ve seen in other societies with the proper leadership, with the proper frame of mind it’s really possible to achieve a remarkable transformation. South Africa is such an example, where you can go from a culture of hatred and the construction of exclusive identities to a dramatically different political space.

Is there a particular historical case, a country that has endured mass political atrocities and gone through a truth and reconciliation process, that might be resonate most strongly with Iranians?

The answer is a definite yes and no in the sense that there are some broad characteristics to the need to reconcile with the past. There is psychological dimension to healing, forgiveness, reconciliation, accountability. Mechanisms raging from truth commissions to prosecutions to educational curricula, so yes in that sense Iran can learn from the experience of many different societies. Argentina, South Africa, probably Yugoslavia tend to be the more well known instances. I think we also have to understand that every country will have its own journey, if you like, and its own peculiarities and circumstances.

I think what’s remarkable about the Islamic Republic is that in many respects it is not just an ordinary tyrannical regime. [If you compare with] let’s say Argentina’s dirty war, crushing what was perceived as a communist threat, what we had [instead] is some kind of cultural revolution. We have a modern totalitarian regime that has invoked a tradition, religion and imaginary past. So I think the challenge in the case of Iran is that we have to deal with a totalitarian system that has really tried to redefine Iranian identity in a very profound way.

It wasn’t just an Argentinian-style dictatorship that was trying to exercise power in a limited way. When we think about the wearing of the hijab, the persecution of religious minorities, we see a regime that really wants a total transformation of cultural identity. So in a sense the struggle against that phenomenon is much more visceral struggle to redefine our identity. It’s not just to get rid of tyranny and have a democratic elections. It’s about reconstituting what it means to a citizen, what it means to be Iranian and what it means to be a human being. What it means to have a just society. So it’s in that context this process of transformation and healing and truth telling has an added burden and importance compared to what we may see in Argentina.

Who presided over the tribunal?

We had other than myself and other Iranian lawyers the likes of Sir Geoffrey Nice a very prominent British barrister who was my colleague at the United Nations, in the Hague and was the lead prosecutor at the Milosevic trial. And then we had a panel of judges presided over by Johann Kriegler, who interestingly was appointed by Nelson Mandela as the president of the South African constitutional court. And the connections were very powerful if you think about getting back to the discussion about South Africa. Here is a man who himself was a white Afrikaner who supported the apartheid, but at some point he decided his consciousness could not allow him to do so, so he turned against the apartheid and then Nelson Mandela, a black president, in a gesture of reconciliation appoints a white Afrikaner as the president of the constitutional court.

And then we had a message of support from Archbishop Desmond Tutu who was the head of the South African truth or reconciliation commission. So I think that’s what really gave this tribunal a global dimension, what gave it credibility, rather than simply a forum where people comment and simply speak about the atrocities.

What are the lessons that the tribunal might have imparted to witnesses, who must have once diverged from one another politically in a significant way?

To me a victim is a victim and it doesn’t matter to me what political affiliations they have. I have worked with leftist groups, with Green reformists and so on and so forth. I know that many of these political groups have very serious disagreements with each other and that’s also part of the backwardness of our political culture. That even in the same political group there are three groups that are fighting with each other. And in a sense our political culture, even in the opposition, even in the diaspora, is a reflection of why we are in the tragic mess that we are in today.

So I think learning the art of dialogue, learning the art of cooperation, cooperating with each other, all of these are really the revolutionary elements that what we need in Iran. A revolution is not some great ideology, some shining city on the mountain top, but is actually something as basic as the art of dialogue and collaboration and listening and sharing of stories and narratives and perspectives. I think in the new generation there is much more impatience with the divisive ideological politics of the older generation and that is part of the process of maturation. And I see this process of dealing with the truth in a depoliticized space as part of this maturation.

What was the most essential part of the tribunal, in your eyes? Is the verdict crucial or the alternative history it makes possible?

We are not only talking here about the legal conclusion of the Iran tribunal, that these mass executions constitute crimes against humanity under international law and the Islamic Republic should be held accountable. Of course that’s important, but just as the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission had 1,000-page report that very few people read, the most important thing was the testimony of the victims and not any particular conclusions that were arrived at. You cannot reduce the enormity of that suffering to either a political slogan or to a legal conclusion.

We need to understand it more as a narrative of human suffering and redemption. And that’s what touches the average person, something that anyone can understand. Anyone can understand the suffering of a mother who has lost her children. And I think in the future the Mothers of Khavaran and others will have a very important role in the democratic transformation. People will not think of a grieving mother as someone who is powerful, but these mothers have an incredible power. [If they did not] why would the regime be so afraid of them? Why would they go and beat and imprison an 80-year-old woman who comes to lay flowers at the symbolic grave of her child at Khavaran. What measure of fear and cowardice compelled the regime 20 years after to dig up all the bodies and dump them elsewhere, so that there is no trace whatsoever of the Khavaran grave site. The regime has become afraid of skeletons.

comments