As with many societies whose recent past has been disfigured by high levels of political violence, today's Iran struggles with the challenge of moving forward without forgetting the traumas that have touched the lives of virtually every Iranian family. Many countries, from South Africa to Argentina, who share such a modern experience, have sought to deal with their pasts through a process of transitional justice – not trials, per se, that seek vengeance against culprits, but occasions for both victims and perpetrators to process their shared trauma and morally realign themselves for a future that does not repeat such acts.

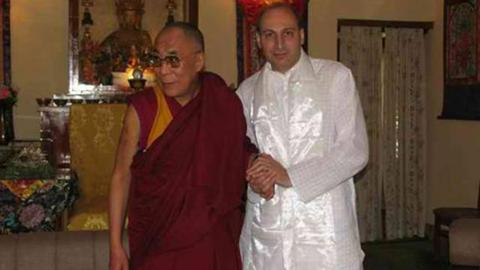

The world-renowned Iranian philosopher and scholar Ramin Jahanbegloo has deep experience with many of these societies, and talks with us here about what the future holds for Iranians, and the crucial role that forgiveness plays in any transition toward democracy. He discusses how Iranian civil society has matured in recent years, the non-violence that Iranians displayed during their 2009 uprising, and what these trends reflect about the exceptionalism of Iran, perched in a region where political upheaval has overwhelmingly been accompanied by intense violence.

Is it possible for a society that has endured a great deal of violence in its recent history to cultivate a culture of human rights and accountability for violence within the framework of its existing government?

Yes, I think few people could deny that contemporary Iran, in light of its political features and religious characteristics, is a country of violence. But I think this observation should not be extended to the rapid conclusion that Iranian society is alien and resistant to any form of non-violent change. Because I think since 1979 and especially in the last 20 years, Iranian civil society and civic actors have produced a lot of civic capacity and potential, which actually have been overshadowed most of the time by what I call ‘the mantle of violence.’

But I think we have to be very attentive to the fact that violence is not a function of fate but it can fail and it usually does. I think that Iranian civil society, intellectuals, Iranian women, Iranian students and Iranian people in general have shown us they can overcome this mantle of violence. The challenge in a country like Iran today is somehow to break this circle of violence, while having a very correct view of the past and the future at the same time. By that I mean to combine the call for truth and the demand for accountability with the act of forgiving and having a transition towards a less violent Iran.

Did people's peaceful protests during the 2009 election uprising demonstrate exactly this point? In the context of the Arab uprisings that followed, nearly all of which were quite violent, does the history of 2009 actually reflect how Iranian society is in a different place with its civic approach to political pressure?

Yes absolutely, I think 2009 proved the maturity of Iranian civil society, because we saw that the choice of non-violent action by Iranians showed that people wish take advantage of their non-violent memories and draw upon their non-violent experiences of the past. For example the Constitutional Revolution of 1906 exemplifies these non-violent attributes and can appeal to civil society. I think people somehow wanted to bring back these experiences.

But at the same time it was also a civil act to go beyond any sense of revenge and vengeance in order to retaliate for past wrongdoings. It shows us that we are facing a new experience in Iranian society, a non-violent transition towards democracy against all forms of authoritarian violence which we had in the past 100 years. So I think the important aspect of 2009 is that it shows there cannot be any struggle for democracy without the prevalence of non-violence as the choice of Iranian civil society. This is a crucial aspect of Iran today, because while we are still in a very violent political society, we can see that we can still have ethical values and choices of non-violent action.

This brings a lot of hope because it shows us that we have one of the rare civil societies in the Middle East where we are thinking about gradual transition to democracy and this gradual transition to democracy goes hand in hand with the respect of civil liberties but also respect of values of human rights.

The international attitude toward the Green movement is that it failed. But your perspective actually situates it in a far more historically significant and meaningful light. Can we therefore, as Iranians, actually view 2009 as a positive and meaningful step, rather than a tragically missed opportunity?

What I was trying to say is that first of all, political violence is not a genetic concept, it’s a political one. So it’s subject to the intergenerational fading of historical memory and I think societies can at the same time internalize and overcome their collective memory of political violence. And that is exactly the story of Iran. It is the same case as in Chile or Spain or in South Africa, it’s the story of a memory, a historical memory, which is struggling over power and over violence and it’s trying to understand its past grievances and sins. Like the executions of the dignitaries of the Shah’s regime in 1979, the war in Kurdistan in 1980, the mass murders of 1987, all aspects of violence we had in the last 35 years but also in the past 100 years. But I also think it’s a way towards the future. We can seek a third way between the extremes of vengeance and national amnesia, and in this way actually I think that Iranian society is trying to find new mechanisms. And especially outside Iran, Iranians are trying to find new mechanisms, not just judicial mechanisms but also social and political ones.

Can you briefly describe what form these mechanisms can take?

The Iran Tribunal is one form of these mechanisms I was talking about, mechanisms of transitional justice which is a repetition, in an Iranian model, of what we saw in South Africa or in Latin America with the truth and reconciliation commissions. One aspect of this is the demand for accountability, but it goes hand in hand with the act of forgiving. Because the thing about forgiving is that it releases national memory from the consequences of what has been done and gives us a capacity to move forward. Otherwise we are always somehow anchored by vengeance and fear of the past.

So as is case with the Latin American, Chilean, Argentinian, and South African commissions, there is a twin goal of prevention and reparation in this process. But this is not, I insist again, that the Iran tribunal or any other aspects which we've been talking about in the past several years, is not just a judicial process but also a process of moral reconstruction.

Because when we talk about forgiveness, we are not replacing a court of justice but trying to say that if we want to go forward, we have to renounce resentment, re-establish the dignity of victims and forge a new social solidarity. We have to think about being able to let go of resentment and vengeance, because it’s actually not only necessarily forgiving the wrongdoer, but it’s also thinking about [developing] an enthusiasm for democracy without the horror of violence, old or new.

The renouncement of vengeance seems like a crucial strand here, but do you think Iranian political activists, inside the country or in the diaspora, have such an attitude? Does their rhetoric convey to the Iranian authorities that if they permit change, their fate will not be the fate of Saddam Hussein or Gaddafi?

I think that the diaspora can play an important role especially in informing people around the world. Each Iranian diaspora within its host country can emphasize the fact that first of all when we talk about Iran, we are not talking just about governmental power, but also a rich culture and history, a complex society and long-suffering people. And secondly I think that the diaspora could always insist, especially in regards to the media, that we have to go beyond any hijacked concepts, concepts which are hijacked by lobbies and groups which give justification for new atrocities, new wars, new forms of violence. So I think the diaspora can play an important role in somehow taking forward this culture of non-violent democracy.

And to stop all the supporters of Dr Strangelove who want to think of the future Iran in terms of new violence, new tyrannies, new forms of military attack or military invasion, mad games in general. Because I think this mad game cannot make sense any more especially for Iranians. The diaspora also can play the role of negotiators or go-between, in between what Iranian society or the somehow voiceless people inside Iran and also the governments and societies outside Iran. This is very important role I think.

Do you think the diaspora is close to doing that? In my experience the diaspora is extremely intolerant and undemocratic in its culture, and that actually people inside Iran perhaps more accustomed to accepting and tolerating different political points of view. Is that too harsh or do you see this as changing?

No that’s very true. But actually what we have to emphasize and I think it’s mostly work of journalists and media to emphasize, is that is that the very notion of ideology has lost much of its coherence among the new generation of Iranians. It’s very important because we see that most younger Iranians they have gone beyond creeds like Marxist-Leninism or Islamic fundamentalism and I think this vacuum is filled today by the category of non-violence civil society, which has become a practical key to the democratic transition in Iran.

So I think that the Iranian diaspora needs to follow upon on this new vision on this new generation of Iranians and try to accommodate itself with this new reality of Iran, which is trying to take forward its democratic practices and new responsibilities and new accountability, especially by showing a very intense interest in global affairs but also in the ways of negotiation and ways of compromising, ways of finding a way out of the cycle of erratic oscillations, in which we have moments of democratic hope in Iran.

One of the problems with the Iranian diaspora around the world is that it’s still living under the shock of the revolution, without having reevaluated its political ideals. So I think the diaspora needs a learning process, which could generate a sense of responsibility and a sense of realism. And this is something that the new generation of Iranians have been through. For them the revolution of yesterday it has become the non-violence of today. So they want to turn the page and with this new enthusiasm of democracy, but also without the horror of violence.

Some Iranian intellectuals and civic actors, such as most recently Akbar Ganji, have argued that we should for the time stop bringing up past abuses and give President Hassan Rouhani the space to broker a compromise with the West. What are your thoughts on that position, which essentially argues that we can't afford to be reconciling with the past at present?

I don’t think it’s a case of reconciling with the past, I think it’s a question of going forward. I talked about the third way between the extremes of vengeance and national amnesia or between apathy and not doing anything, and having a violent ideology and thinking to destruction of everyone in terms of transition to democracy. I think it’s more than that. The problem today for most younger generation Iranians it’s not only to attain victory for democracy but also to be mindful of the terrible past on which this democracy will come one day. It’s a moral responsibility for the whole Iranian nation. We have to actually rethink the question of Iranian guilt, if we can talk about it in this way, in the same way we speak of German guilt.

We should not, as many do, think only think in terms of prosecuting the criminals, we have to think also in terms of reevaluating our responsibility for the future of Iran. This is very, very important. It’s a question of how to rebuild the institutions in Iran and how to bring in concepts like justice and reconciliation, where you already had a crime, where you had violence. Therapeutic power, or national healing, which can help us to have this transition in democracy. I don’t think we can do it by political acts, we need to have that also at the level of like in the Iran Tribunal, we need to have it at the level of going and thinking about ourselves and our past, remembering our acts violence and how they have affected us, rethink of new ways of condemning these acts of violence but also turning the page and going forward. In one word we have to turn our human wrongs into human rights.

Are there countries whose experience with transitional justice can be a constructive example for Iran?

From my experience actually, which goes back to the time when I was working with the Eastern Europeans in the past thirty years , we have in Latin America, in the 1980s, in Eastern Europe in Poland and Hungary and the Czech Republic, and we also had it in South Africa. Most of these experiences showed us the work of national reconciliation in different countries but also the work of transitional justice, which was not necessarily a radical break with the past. These countries tried not to have a radical break with the past, but tried to find a model for the future with transitional justice or restorative justice.

After many talks I had with them, I have visited most, of them I think they had to reeducate themselves to face their political traumas and revisit their historical violence. But they could not do that through a new forms of violence. I think what they did was to try to find ways to get out of resentment and vengeance and of course to do that they needed to shape a new political discourse and this new political discourse and this was discourse of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Mandela and Desmond Tutu, for example, always talked in terms of a reconciled people, because they said without having a reconciled nation we cannot have a future. In terms of the future of Iran, we need to have this reconciliation and this reconciliation should come – of course it’s difficult to prescribe it as a normative model -- but it can be recommended as a moral intelligence that takes us out of the entanglement of vengeance and resentment. This is what I’m concerned with about the future of Iran. I’m not that much concerned with the past because the past is not going to dehumanize us anymore. But I’m concerned with the perpetration of the future crimes in Iran and eventually how we should think of it even right now, before getting there. This doesn’t mean that we are not remembering the past but we don’t want to repeat it. These are two different things.

It seems to me that Iranian society, even at the level of popular culture, is developing that kind of consciousness. For example, the film ‘A Separation,’ showed how Iranians 'other' one another, or dehumanize one another, across socio-political differences. It reflected this awareness that we need to move beyond that tendency in order to forgive one another on a basic human level. Do you feel that kind of growth is capture by the media, and reflected back to Iranians?

I think most of the times the media that talks about Iran is very polarized actually. And this polarization [hampers] journalists, especially those who don’t have an Iranian, background, from seeing that beyond the violence they see in Iranian society, or the political violence coming from the government, there are actually high degrees of non-violence practiced in Iran. That’s why I think it’s important to have two channels towards Iran: one, a channel of diplomatic discussions and dialogue with the Iranian government; but the other should be a channel of dialogue with Iranian civil society and the Iranian people themselves.

The more we have this dialogue with the Iranian people themselves, the more we can learn about their views and the changes that have appeared in Iranian society. I think once again we go back to the fact that non-violence today, as it has been practiced by different civic actors in Iran, is not only considered a strategy for winning a conflict or winning a political ideology, but it's practiced as a new mentality that makes it impossible for future arbitrary rulers to control the lives of Iranian citizens.

It’s much more difficult than it used to be in 1906 or 1979 because Iranians are asking more questions today. This is where journalists have to understand that we are talking about a new Iran. Despite a century of undemocratic violence, this is a young society that looks back across its history and says, well I want also to learn from my non-violent experiences and also to learn from the experiences people had in other countries. Especially how people in other countries turned the page and moved towards this new imperative, which is democratic non-violence. What 2009 showed us was that we had the prevalence of non-violence and especially with this choice of silent demonstrations civil disobedience and this kind of a more of a reformist challenge than an ideological challenge.

President Rouhani's visit to New York seems to have secured for Iran, at least for now, a second chance, both diplomatically and also before global public opinion. What can we look to as a measure of change?

It’s important to mention the fact that when we talk about Iran we talk about a people, a history, a culture. I think essential changes, meaningful changes appear more among these people and this history and this culture rather than with the governments. I’m not saying that you might not see a will for change or reform among the governors of Iran, but I’m saying that the most meaningful change comes from the Iranian people themselves, and there that you can find this self motivation of acting non-violently and somehow going towards a more peaceful change and putting aside all these ideological gestures of the past which brought us state violence mainly in the past hundred years.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments