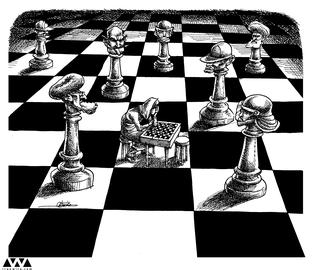

Every horrifying report on executions in Iran, every nightmare photograph of a public hanging, is apt to evoke in European observers feelings of political memory, a cold sense that we have been here before.

As Iranian abolitionists confront the phenomena of public killing and capital punishment in their own society, and build upon their own literature of opposition, they may take inspiration from the rich body of arguments through which 19th and early 20th century literary giants (most of whom had close-up experiences of judicial killing) influenced attitudes in the West.

The modest anthology of ideas below lightly touches the immense literature on the subject in the West, and includes, for context, arguments from a Christian perspective that cannot influence policy in Iran. The secular challenges to the death penalty, it is hoped Iranian readers may agree, remain beautiful, memorable – and universal.

Charles Dickens

In 1849, Charles Dickens wrote to The Times of London to express his horror at a public hanging he had witnessed outside a south London prison. Although he adopted a limited strategy, assuring readers he had no “intention of discussing the abstract question of capital punishment or any of the arguments of its opponents or advocates,” his focus on a clear target – public executions – and an immediate goal – supporting a political initiative to make capital punishment “a private solemnity within prison walls” – facilitated a forceful polemic. Dickens argued from several entwined positions:

The argument from shame. Dickens shamed the attending crowd – and by extension readers who approved of such gatherings – by reference to its “wickedness and levity”, its “atrocious bearing, looks and language”, and the presence within it of “thieves, low prostitutes, ruffians and vagabonds of every kind”.

The argument from Christianity. In a manner now alien to western polemic, Dickens appealed to his readers’ sense of religious supremacy by writing that the scene “could be presented in no heathen land under the sun,” and to their supernatural beliefs by arguing that the spectacle was essentially irreligious: “When the two miserable creatures...were turned quivering into the air, there was no more emotion, no more pity, no more thought that two immortal souls had gone to judgment...than if the name of Christ had never been heard in this world.”

The argument against brutalization. Dickens wrote that the behavior of children at the hanging “made my blood run cold”, and that innocent witnesses would be corrupted by the sight of judicial killing and the crowds that attended it: “I do not believe that any community can prosper where such a scene of horror and demoralization as was enacted outside Horsemonger-lane Jail is presented at the very doors of good citizens.”

Fyodor Dostoevsky

The same year Charles Dickens denounced public hanging in London, Fyodor Dostoevsky was sentenced to death by firing squad in St. Petersburg for reading Vissarion Belinsky’s Letter to Gogol at a political meeting. In the letter, Belinsky attacked serfdom and described the Russian Orthodox Church as a prop of despotism. Tsar Nicholas I commuted his death sentence, condemning him to a mock execution and four years of hard labor instead.

Dostoevsky’s most memorable passage about capital punishment appears in his 1869 novel The Idiot, in which the protagonist, Prince Myshkin, recalls witnessing a public execution by guillotine in France. Myshkin argued from two main positions:

The argument from Christianity. Myshkin raises arcane anxieties about the state of the condemned man’s soul at the moment the guillotine blade drops: “What happens at that moment with the soul, what convulsions is it driven to? It’s an outrage on the soul.” He adds an implication of religious hypocrisy: “It’s said, ‘Do not kill.’ So he killed and they kill him. No, that’s impossible.”

The argument for empathy and against disproportion. Myshkin expresses intense empathy for the condemned man, and imagines the unnatural ways in which the speed and certainty of death by guillotine torment him: “Think: if there’s torture, for instance, then there’s suffering, wounds, bodily pain, and it means that all that distracts you from inner torment, so that you only suffer from the wounds until you die. And yet the chief, the strongest pain may not be in the wounds but in knowing for certain that in an hour, then in ten minutes, then in half a minute, then now, this second—your soul will fly out of your body and you’ll no longer be a man, and it’s for certain. When you put your head under that knife and hear it come screeching down on you, that one quarter of a second is the most horrible of all...To kill for killing is an immeasurably greater punishment than the crime itself.”

Leo Tolstoy

Dostoevsky’s contemporary, Leo Tolstoy, drew similar conclusions about the “revolting” guillotine when he witnessed an execution in Paris in 1867. The experience changed his life, igniting his sense of individual responsibility.

The argument from conscience. Tolstoy tied his criticism of capital punishment to his responsibility to break with consensus as dictated by conscience: “When I saw the head part from the body and how it thumped separately into the box, I understood...that no theory of the reasonableness of our present progress could justify this deed, and that though everyone from the creation of the world, on whatever theory, had held it to be necessary, I knew it would be unnecessary and bad...the arbiter of what is good and evil is not what people say and do, nor is it progress, but it is my heart and I.”

In 1866, while Tolstoy was writing War and Peace, he agreed to defend a Russian soldier, accused of striking an officer, in a court martial. His defense failed, and the Russian military executed the man by firing squad. The episode appears to have influenced a powerful passage in War and Peace (1869).

In the novel, Tolstoy depicts the French occupation of Moscow during the Napoleonic Wars, in the course of which the French arrest his protagonist, the Europeanized Russian Pierre Bezukhov, believing him to be a spy. Bezukhov argues for his life, and witnesses the execution of Russian prisoners, who have been accused of setting fire to the defeated city, by French firing squads. He illustrates the horror of execution by two main methods:

The argument from common humanity. When Pierre appeals to a distracted French officer, he experiences a moment of identification with him through eye contact. Tolstoy narrates, “In that gaze, beyond all the conventions of war and the courts, human relations were established between these two men. In that one moment, they both felt vaguely a countless number of things and realized that they were both children of the human race, that they were brothers.” When the executions begin, Tolstoy emphasizes the human habits of the condemned, even as they are blindfolded and tied to posts, waiting to be shot. One man “scratched his leg with his bare foot” and “straightened the knot at the back of his head, which hurt him”.

The argument against brutalization. Pierre shows empathy not only for the condemned, but for the French executioners, who harm themselves by acting out of convention rather than conviction: “On the faces of the French soldiers and officers, on all without exception, he read the same fear, horror, and struggle that were in his heart. ‘But who, finally, is doing this? They are all suffering just as I am. Who is it? Who?’”

Pierre recognizes the French soldiers’ discomfort and brutalization as they untie the dead and cast them into a pit: “Frightened, pale people...They all obviously knew without question that they were criminals, who had to quickly conceal the traces of their crime.” He describes “a young soldier with a deathly pale face [who] went on standing across from the pit in the place from which he had fired. He was reeling like a drunk man...” Another executioner remarks, “That’ll teach them to set fires,” but, Pierre observes, “it was a soldier who wanted to comfort himself at least somehow for what he had done, but could not. Without finishing what he was saying, he waved his arm and walked away.”

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka’s short story In the Penal Colony (1914) is a work of penetrating psychology, not polemic, but the ways in which it unsettles the reader overlap with abolitionist arguments.

Kafka tells of a traveler visiting an obscure and unnamed tropical penal colony, in which a zealous officer executes prisoners by means of a “strange piece of equipment” that tortures them to death by engraving laws on their bodies in elaborate calligraphy over the course of 12 hours, in public.

By demonstrating the elaborate machine, the hardline officer seeks to enlist the traveler’s support against a new commandant who has “shown some interest in meddling” with his proceedings.

The tale offers up one central – and quite unusual – abolitionist idea:

The argument against investment in ritual and tradition. The hardline officer so reveres the art of execution, its traditions, its rituals, its paraphernalia, and its inventor (who it is prophesied will rise from the dead) that he perpetuates a practice almost everyone in the colony avoids witnessing or wants abolished. “Do you think,” he asks the traveler with incredulity, “that such a lifework...should be allowed to rot?” He recalls with nostalgia the days when crowds of visitors came to view the executions, and the old commandant gave children the best seats.

The hardline officer’s chief fear is that the traveler will humiliate him by expressing doubt or indifference about his method of execution to the colony’s new commandant. The traveller’s opinion will carry great weight because he is an objective witness, and the officer begs him for support and tries to coach him for a potential meeting with the new commandant. When the traveler refuses, the officer is so ashamed, so eager to prove his faith in his process, that he releases the condemned man and condemns himself to death in the machine, which will inscribe the words “Be just” on his body. In a final humiliation, the machine malfunctions and impales him instead.

George Orwell

George Orwell witnessed the execution of an Indian man while working as a British colonial policeman in Burma, and wrote about it in one of his best-known essays, A Hanging, in 1931. He built the essay around three main rhetorical techniques.

The argument from common humanity. Orwell focuses in fine detail on the ordinary human behavior of the “healthy, conscious” condemned man who, even as he is being led to the gallows, steps aside to avoid a puddle. He writes: “I saw the mystery, the unspeakable wrongness, of cutting a life short when it is in full tide. This man was not dying, he was alive just as we were alive. All the organs of his body were working – bowels digesting food, skin renewing itself, nails growing, tissues forming – all toiling away in solemn foolery. His nails would still be growing when he stood on the drop, when he was falling through the air with a tenth of a second to live. His eyes saw the yellow gravel and the grey walls, and his brain still remembered, foresaw, reasoned – reasoned even about puddles. He and we were a party of men walking together, seeing, hearing, feeling, understanding the same world; and in two minutes, with a sudden snap, one of us would be gone – one mind less, one world less.”

The argument from shame. Orwell uses as literary device the presence of a dog at the scene of the execution, which, “before anyone could stop it...made a dash for the prisoner, and jumping up tried to lick his face”. Orwell restrains the dog during the execution, but after the condemned man has been hanged, it “galloped immediately to the back of the gallows; but when it got there it stopped short, barked, and then retreated into the corner of the yard, where it stood among the weeds, looking timorously out at us.”

The argument against brutalization. In an echo of Dickens’s condemnation of the levity of crowds, and of Tolstoy’s interest in the moral damage executioners inflict upon themselves, Orwell focuses on the behavior of the other observers. One remarks that the condemned man had “pissed on the floor of his cell”, and others laugh. The head jailer comments that the execution “passed off with the utmost satisfactoriness” since he has known cases in which a doctor had to “go beneath the gallows and pull the prisoner’s legs to ensure decease”. A Burmese magistrate laughs at this, as does Orwell. “The dead man,” he recalls, “was a hundred yards away.”

In his dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) Orwell envisioned a brutal quasi-theocracy that had re-introduced public hanging to Britain, with all its brutalizing effects, especially on children.

The argument against brutalization. Orwell’s protagonist, Winston Smith, visits a neighbor’s flat to unclog a sink, and encounters her aggressive children (one of whom threatens to “vaporize” him), who are misbehaving and nagging because their mother is too busy to take them to a hanging.

The argument against sadism. Orwell points out that some people enjoy cruel spectacles, and expect others to enjoy them, too. Winston encounters a “venomously orthodox” colleague, Syme, who asks him if he saw prisoners hanged the previous day. To avoid disapproval, Winston says he’ll see it “on the flicks”. Syme retorts, “a very inadequate substitute.” Syme, Winston observes, “would talk with a disagreeable gloating satisfaction of helicopter raids on enemy villages, the trials and confessions of thought criminals, the executions in the Ministry of Love”. Syme assures Winston that “It was a good hanging...I think it spoils it when they tie their feet together, I like to see them kicking. And above all, in the end, the tongue sticking right out, and blue – a quite bright blue. That’s the detail that appeals to me.”

Sources:

Dickens, Charles. "Mr. Charles Dickens and the Execution of the Mannings". The Times, 1849

Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Idiot. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Frank, Joseph. Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Kafka, Franz. The Metamorphosis and Other Stories. Translated by Michael Hofmann. London: Penguin Books, 2007.

Tolstoy, Leo. War and Peace. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

Wilson, A.N. Tolstoy: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2001.

Orwell, George. Essays. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Orwell, George. Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Penguin Books, 1990.

This article was originally published on March 19, 2014

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments