"Syria is our strategic province," said Mehdi Taeb, the cleric in charge of the Revolutionary Guards' Cyber Warfare Unit in February 2014. "If we have a choice between defending the province of Khuzestan (of Iran) or Syria, we will choose Syria. Becaus if we lose Syria, we won't be able to defend Khuzistan either." This is the bluntest comment from a senior Iranian official about an alliance of convenience that started in the early 1980s, an alliance that has reflected its shared enmity with Iraq and Israel. Syria was the only Arab country to support Iran diplomatically and through arms supplies during its eight-year war with Iraq, and geographic factors allowed Iran to support Syria in Lebanon following the Israeli invasion in 1982, and to export its revolutionary pan-Islamism in the process. While the two regimes presided over very different ideologies, their relationship has proved one of the most enduring in the Middle East. Now, as the Assad regime deploys catastrophic violence to survive, and sectarian conflict spills from Syria into other Iranian spheres of interest, Iran considers its options.

Uneasy Relations

Relations between Iran under the Shah’s regime and Syria under Hafez al-Assad were often strained, but also occasionally cooperative. “They were pretty problematic,” says Jubin Goodarzi of Webster University in Geneva, and author of Syria and Iran: Diplomatic Alliance and Power Politics in the Middle East. Syria adhered to a pan-Arab socialist ideology—a strain of Baathism—and resented the Shah’s relations with the United States, Israel, and the West. The two countries disagreed too over the nomenclature of the Persian Gulf—which Syria called the Arabian Gulf—and of Iran’s Arab-inhabited Khuzestan province, which Arab nationalists called “Arabistan.”

Iran made occasional gestures to improve ties, Goodarzi says, notably after the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, when the Shah allowed wounded Syrians to be flown to Iran for treatment, and offered Syria financial aid. Assad, he writes in his history of the relationship, was also keen not to be outmanoeuvered by Iraq following its settlement of disputes with Iran through the 1975 Algiers accord. “But overall, that did not lead to a genuine thaw and rapprochement, especially after Egyptian President Anwar Sadat started to thaw relations with Israel.” As Syria’s leadership saw Sadat “go solo,” by pursuing his own peace with the Jewish state, Goodarzi says, it looked to the Shah to persuade Sadat to take greater consideration of his Arab neighbors’ interests. Instead the Shah encouraged Sadat’s peace initiative.

With relations in decline again, Goodarzi says, Syria provided sanctuary to opponents of the Shah’s regime, notably Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, who later became one of the lieutenants of Ruhollah Khomeini.

A Net Gain for the Arab Cause

Syria met the Iranian Revolution with enthusiasm. It was the first Arab country to recognize the new provisional government of Mehdi Bazargan, and the third overall, following the Soviet Union and Pakistan. In the months that followed, Goodarzi says, Syria was keen to cultivate close ties. “They thought that this would be a net gain for Syria, and to the Arab cause, in view of the fact that the revolution in Iran expressed solidarity with the Palestinian cause.” Moreover, he says, the revolution coincided with the failure of unification talks between Baathist Syria and Baathist Iraq (which had accused Syria of planning a coup against the Baghdad regime), and immediately followed Egypt’s signing of the Camp David agreements, which removed it from the Arab-Israeli conflict. Assad, writes Mohsen Milani of the University of South Florida, saw revolutionary Iran as a counterforce against Iraq and Israel, and sent Khomeini a gold-illuminated Koran and a pledge of cooperation in 1979.

The relationship, writes historian David W. Lesch of Trinity University in Texas in Syria: the Fall of the House of Assad, developed into a strategic alliance for which the best explanation was the Arab proverb, “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Since Syria was often at odds with other Arab states, he writes, “It did no harm to have a powerful friend, especially one on the other side of the Arab state that had been most problematic to Syria since the 1970s: Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.” For Iran, he writes, the ability to extend support to anti-Israeli Islamist groups—Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Palestinian Territories—was important to its definition of its revolutions as Islamic, and therefore not confined to Iranian borders.

The pairing between an Alawite-dominated and notionally secular Syria and Iran’s Twelver Shia Islamic state was counterintuitive but paradoxically, Goodarzi says, their ideological distance also helped the relationship: “The latter part of the 20th century has demonstrated that authoritarian or totalitarian regimes that espouse the same trans-national ideology often end up being competitors—the classic examples are Baathist Syria and Baathist Iraq, and Communist governments in the Soviet Union and China.” Since Syria and Iran did not compete ideologically they were united, he says, by overlapping views on Iraq and Israel, and a shared desire to minimize Western penetration of their region.

Loyalty Defined by War

Two wars solidified the relationship between the two countries. “Iran-Syria relations are perhaps the most enduring alliance between two Middle East countries since the end of World War II,” says Reza Marashi of the National Iranian American Council in Washington, D.C. “It’s no secret that the Iran-Iraq war deeply shaped the worldview of nearly all key Iranian decision-makers, and they are unlikely to forget or turn their back on Syria after its support during those hellacious eight years.”

During that war, Goodarzi says, there were reports that Syria helped Iran identify Iraqi troop concentrations, provided light arms and missiles, and gave Iran guidance regarding the Soviet-made equipment that Iraq used. But more important than Syria’s military assistance, he says, were the other forms of backing it offered, such as shutting down an Iraqi oil pipeline that crossed its territory, and sabotaging an Arab League meeting in Amman during which King Hussein of Jordan tried to rally support for Iraq.

Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 further cemented relations. “When Israel’s occupying forces swiftly defeated Syrian forces,” Marashi says, “Hafez Assad turned to Iran for assistance to protect Syrian interests—and Iran delivered.” Syria had entered Lebanon in 1976 as a nominal peacekeeper and preserver of the status quo. By the time of the Israeli invasion, Goodarzi says, Iran had gradually expanded its influence in Lebanon and was able to mobilize Lebanese Shiites to take up arms both as guerrilla fighters in the country’s south, and against the multinational peacekeeping force comprised of American, French, British, and Italian contingents as well as Israeli forces.

But events in Syria in 1982 posed an early challenge to Iran’s pan-Islamic posture. Syria had faced unrest from the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood from the late 1970s, Goodarzi says, and when the group took over Hama in March 1982, the Syrian regime then carried out a massacre in the city, killing over 10,000 people. “The Syrian Muslim Brotherhood were a group with immaculate Islamist credentials, but I talked to Iranian figures who had been in power in the early eighties who said, ‘Yes, the Muslim Brotherhood are an Islamist political party, but they compromised themselves by getting assistance from countries such as Jordan and Iraq.’” Iran’s state-controlled media, he says, first imposed a news blackout on the Brotherhood’s activities, but after the Hama massacre, Iran condemned the group as an ally of Jordan and Israel. While Khomeini issued a mild condemnation, Iran’s relations with Syria did not change.

In the mid 1980s, as Iran pushed Iraq from most of its territory and Israel withdrew from parts of Lebanon, Goodarzi says, Iran and Syria developed conflicts of interest, particularly regarding their respective visions for Lebanon. Syria supported Amal, a political party and militia that had long represented Lebanon’s Shiites, and backed a secular and multi-confessional state, while Iran backed Hezbollah and envisionedN greater power for Lebanon’s Muslim population, and its Shiites in particular. Syria, he says, spoke of rapprochement with Jordan and Iraq, and the head of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood visited Iran. But by the late 1980s, The two countries reached an understanding that Syrian interests would lead in the Levant, while Iranian interests would predominate in the Persian Gulf. As Iraq reasserted itself militarily in the late eighties, and the moribund Soviet Union withdrew support for Syria, relations improved, with Syria now the weaker partner.

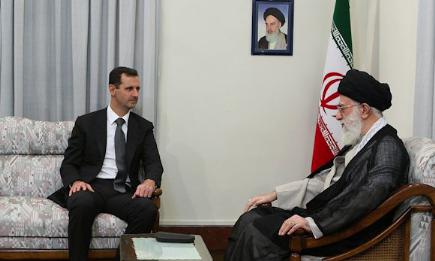

Former Iranian president Al Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani is pictured with Hafez Al-Assad, father of Bashar Al-Assad (undated).

From Gulf War to War on Terror

The 1990s saw a further confluence of interests between the two countries, even if they each pursued different methods. “Throughout the 1990s they pooled their efforts to contain Saddam Hussein,” Marashi says. “Syria joined George H.W. Bush’s coalition during the first Persian Gulf War, and Iran took a neutral position despite the threat of American troops on its border.” Syria, Goodarzi says, had responded to American promises to renew efforts to resolve the Arab-Israeli dispute, while Iran, exhausted from the Iran-Iraq war, exploited its neutrality to get POWs back, and even to feign such a degree of sympathy with its old enemy.that Iraq risked seeking refuge in Iran for a section of its air force in 1992, only to have132 aircraft confiscated.

The United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq brought more urgent collaboration. “Tehran and Damascus used their political, economic, military and intelligence capabilities in Iraq to ensure that the country would not become a launching pad for an American attack directed at them,” Marashi says. But as America got bogged down, he says, both countries saw an opportunity for power projection in Iraq rather than defense.

Although both parties fuelled the insurgency in Iraq to tie down U.S. forces, Goodarzi says, they treated the country differently, especially after 2005. Iran looked more favorably on the Shia-dominated Maliki government than Syria did, he says, since Iran could influence Shia groups. Syria, enjoying little such influence, provided refuge for Iraq’s former Baathists, and allowed Sunni Islamists, including Al Qaeda, to use Syria as a springboard for attacks on both the Iraqi government and U.S. forces. “As we know, after 2011 the Syrians suffered blowback because the same groups the Syrians had sheltered turned against them.”

From Azadi Square to the Syrian Front

Syria met Iran’s 2009 Green Movement protests with caution. “Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi were part of the Iranian political establishment,” Goodarzi says, even if they were more pragmatic than Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. “The Syrians said, ‘We want the Iranian political elite to work this problem out among themselves.’ They did not want there to be a major political crisis or breakdown or civil war.”

When Arab Spring protests reached Syria in 2011, Iran took a similar approach to Syria. “Iranian elites took a wait and see position,” says Farzan Sabet, managing editor of the website IranPolitik and author of The Islamic Republic’s Political Elite & Syria. “One early position they took was to distinguish what was happening in Syria from the Arab Spring, which they labelled an “Islamic Awakening” inspired by Iran’s own Islamic Revolution.” Iranian press reports, he says, suggest there may have been divergence over the extent of President Bashar Al-Assad’s crackdown, with some seeing it as worsening the situation. Although glimpses of those divergences are rare, he says, one example was former President Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani’s apparently accidental acknowledgement of Assad’s use of chemical weapons in a message he quickly retracted. In 2013, Ahmed Bakhshayesh, a member of the parliament’s Security and Foreign Policy Commission, told Time magazine that there was no doubt Assad was a dictator.

Some in the Iranian leadership disapproved of Bashar’s response, viewing it as excessive and destabilising. “Iran’s first reaction was to open its own playbook and show Assad pages from the post-election protests in 2009,” Marashi says. “Decision-makers appear to have hoped that Assad would use enough brute force—arrests, beatings, and a limited amount of killings—to spread fear and quickly re-establish control. The Syrian government appears to have preferred the strategy of the late Hafez Assad.”

Iran, Sabet says, fears losing access to the Levant through the fall of Assad, and the deterrence capability that access would afford it in the event of an Israeli strike against Iran. But Iran, he says, also fears threats to its interests posed by sectarian actors throughout the region, which have besieged Iranian allies such as Hezbollah and Iraqi Shia politicians and militias within their own borders, and have challenged Iran as far from Syria as the Iran-Pakistan border: When the Sunni Balochi terrorist group Jaish Al-Adl kidnapped five Iranian border guards and killed one of them earlier this year, he says, it justified its action on the grounds that Iran supported the Assad regime and its killing of Sunnis.

While rival nations in the region, particularly Saudi Arabia and Qatar, view Iran’s support for Syria from a sectarian perspective, Iran arguably has broader strategic concerns. Iran sees Syria in geopolitical terms, Sabet says. “Although it is erroneously assumed that Iran is aiding the al-Assad regime because of the latter’s Alawite background, Alawites are well outside the mainstream of Iranian Shia.” The Iran-Syria alliance, he says, is not a Shia-Alawite fraternity, but a relationship that is based on overlapping interests, namely both countries’ ability to sustain an “Axis of Resistance” by which to support Hezbollah against Israel. Rising sectarian tensions, he says, have also weakened Iran’s abilities to cooperate in the region, as indicated by recent turbulence in Iran’s relations with Hamas.

Although Iran characterizes the Syrian opposition as foreign-backed terrorists, Marashi says, President Hassan Rouhani has also spoken of cease-fire and political reconciliation. “If that seems bipolar, that’s because it is,” he says. “Iran will continue to provide political, economic, military and intelligence support to the Syrian government, but it also signals its willingness to use the leverage it has built in Syria for a political solution.”

Absent a military solution to the conflict in Syria, Goodarzi says, Iran faces a stalemate that has led to the fragmentation of the whole Levant, and has seen new enemies of Iran, such as ISIS, emerging. Iran, he says, will likely continue to support Assad, but its main goal will be to prevent the emergence of a hostile state. “If they have to sell out Assad, if there is ever some kind of transitional unity government in Syria they will want to make sure that the new government will not be hostile to Iran, even if it is not an ally.”

comments