In December, Iran revealed a Hebrew-inscribed memorial to Iranian Jewish soldiers who died fighting Iraq between 1980 and 1988. The move was apt to confound observers familiar with former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s Holocaust denial, but the story of Iran’s Jews is often subtler than headlines allow. Judaism has been practiced in Iran as a minority faith since 721 BCE, almost twice as long as Islam has existed. Although many Iranian Jews fled Khomeini’s Islamic Revolution in 1979, a community numbering between 10,000 and 25,000 people remains, which means there are more Jews in Iran than in any other country in the Middle East outside of Israel. And while the Iranian government keeps Israel and Zionists high on its list of enemies, Iranians are the least anti-Semitic people in the Middle East, with just over half the population expressing negative views about Jews in a 2014 survey.

Iran’s Jewish communities do not enjoy the same rights as Shia Muslims. They cannot climb the ranks of the government or the military. Courts do not consider them reliable witnesses and do not allow them equal inheritance rights. But the Iranian government accords them marginal rights. As one of Iran’s five officially recognized religious minorities, Iranian Jews are entitled to a single representative in parliament. Jewish MP Siamak Moreh Sedgh has represented the community since 2008, and is quick to tell foreigners he is not oppressed. Unlike Baha’is, whom Iran deems enemies of the state, the Jewish community can freely operate places of worship and religious schools, and even receives government funding to do so.

The First Iranian Jews

Iran’s Jewish communities trace their ancestry to 721 BCE, when the Assyrian King Sargon II sent conquered Israelites to northern Persia. In 539 BCE, the Achaemenid emperor Cyrus the Great forged a momentous link between Persia and ancient Jewry when he liberated Jewish slaves from Babylon. Many of them, says Houman Sarshar of the Center for Iranian Studies at Columbia University, migrated east to settle along trade routes throughout Iran. “During the Achaemenid period, they participated in every level of society.”

The arrival of Islam in Iran in 636 BCE imposed the terms of the Pact of Omar — an agreement originally signed by the Caliph Omar and the Christians of Palestine — on Jews and Christians in Iran. Both minorities had to pay the new Muslim rulers a special tax in recognition of Islam’s supremacy. “In the eyes of Islam,” Sarshar says, “there were two kinds of non-Muslims: there were ‘believers of the book,’ who had the right to live freely as long as they paid the poll tax, otherwise they were subject to execution, and there were non-believers who were not people of the book, and that included Buddhists, Zoroastrians and the like, who were given the option of conversion or death.” Muslims considered Jews people of the book.

Even in the Islamic period, some Jews thrived in Iran. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Sarshar says, there were Jews who became important figures in government. One in particular, the polymath Rashid al-din Hamedani, who converted to Islam, was one of the most powerful governors of his time,. Hamedani’s influence in Iranian government lived on for centuries, in part because he standardized weights and aspects of Iran’s monetary system. He was, however, killed for treason in 1318 after being accused of poisoning the Ilkhanid King Oljeitu.

The rise of the Safavid dynasty in 1501 and the establishment of Shia Islam as the state religion in Iran, Sarshar says, initiated an era of oppression. “Life became very complicated for all non-Shiites, but the Jews had an exceptionally hard time until the end of the 19th century,” Sarshar says. “Jewish communities suffered many pogroms throughout the land for various reasons, mostly because the governments and the ruling clergy found that [intimidating Jewish communities to extort money] was a very lucrative thing to do.” Some Jewish communities, he says, ceased to exist. Prospects for Jews began to improve in the late 19th century. In 1898, Nasser al-din Shah of the Qajar dynasty allowed an international organization, the Alliance Israelite Universelle, to found Jewish schools in Iran, which went on to produce generations of French-educated Jews who would participate in the westernization campaigns of the coming century.

Pahlavi Rule: Championing National Identity

Iran’s Constitutional Revolution of 1906 created conditions more favorable for most of Iran’s minorities, and reserved a Jewish seat in the new parliament and abolished the second-class position of Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians. The modernizing dictator Reza Khan, who seized power in 1921 and crowned himself Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1925, sustained those changes. Iran’s new authorities, Sarshar says, made it illegal to collect special taxes from minorities, and lifted restrictions pertaining to property, allowing Jews to become more active in Iran’s economic life.

Reza Shah’s rule put national identity above religious identity. “The greatest contribution of the Pahlavi era was the creation of a civil basis for belonging to the Iranian nation,” says Lior Sternfeld, lecturer in Middle East Studies at the University of Texas. “The fact that Reza Shah and his son Mohammad Reza were at odds with clerics and religious organizations allowed Jews a place in the public sphere.” By the late 1970s, he says, the nation-building project initiated by Reza Shah and continued by his son had allowed Jewish people to enter the economic and industrial elite, and to find places in higher education and unions. “They were less than one per cent of the population, but they were very much integrated into the emerging middle class.”

Although the Pahlavi era overlapped with the early years of the Zionist movement that established Israel in 1948, Zionism held only limited appeal for Iranian Jews. “Iranian Jews are not, as a community, a Zionist community,” Sarshar says. While the creation of Israel was followed by a short period of Jewish emigration from Iran, he says, many Jews who emigrated returned to Iran out of disappointment with Israeli prejudices against Iranians, and out of a desire not to miss out on Iran’s economic prosperity. “History proves they were right to return, because those who stayed in Israel remain among the least wealthy first- and second-generation Israelis,” he says.

Khomeini: “Our Jews are not Zionists”

Some Iranian Jews participated in the Iranian Revolution of 1979, and a Jewish charity hospital, the Dr. Sapir Hospital in Tehran, won credit with revolutionaries for aiding and protecting anti-Shah protesters injured by the Shah’s forces. But after the revolution, as many Iranians fled an uncertain future, the majority of Iranian Jews left too. A population of about 100,000 Jews, Sarshar says, quickly halved, as about 50,000 sought new lives abroad. Some went to Israel or New York, but most ended up in Los Angeles. “As a result of this mass emigration, what used to be a very diverse community of Jews who lived in most large cities converged on Tehran.” While there remained a sizable Jewish community in Shiraz, he says, populations elsewhere —including the ancient Jewish community in Hamadan — shrank to a few families.

Many Jewish people who remained in Iran took alarm at the post-revolutionary atmosphere. Just three months after Khomeini’s return from exile, the bullet-filled corpse of a leading Jewish industrialist, Habib Elghanian, who authorities had executed for friendship with Israel and “warring against God,” appeared in newspapers. A group of Jewish leaders travelled immediately to Khomeini’s home in the seminary town of Qom to seek a guarantee of safety for Iran’s Jews. Khomeini reassured them. “There was a change in Khomeini’s way of speaking about Jews and Judaism before and after the revolution,” Sternfeld says. “Before the revolution you could trace anti-Semitic inclinations. After the revolution, he said, ‘We differentiate between Jews and Zionists.’ He promised Jews that they wouldn’t be persecuted as long as their loyalty to Iran remained intact.”

Anti-Zionist Paranoia

Although the Iranian government distinguishes between Judaism and Zionism at an official level, the distinction is sometimes a cosmetic one, especially for the security establishment. “Whenever they want to hassle Jews in Iran,” Sarshar says, “they label them Zionist spies and create legal problems for them, when everyone knows it’s just a form of anti-Semitism.” In one infamous 1999 case 13 Iranian Jews from Shiraz were arrested and accused of spying for Israel, and 10 were sentenced to long prison terms. They were eventually released following an international campaign. Even non-Jews arrested in Iran for intellectual or journalistic activity have described how authorities accused them of involvement in Zionist conspiracies because they were acquainted with Jews or had taken an interest in the Holocaust.

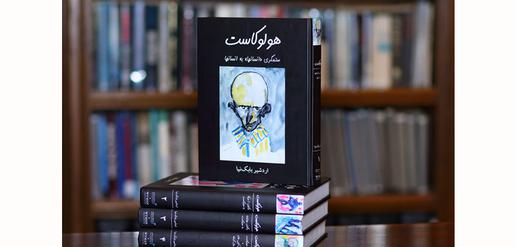

In 2005, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won Iran a reputation as a stronghold of Holocaust denial by calling the Nazi extermination of Jews during the Second World War a “myth.” Maurice Motamed, who served as Iran’s Jewish MP from 2000 to 2008, objected publicly. "Denial of such a great historical tragedy that is connected to the Jewish community can only be considered an insult to all the world's Jewish communities,” he said. But he added that, in view of Iranian Jews’ relationship with Iranian society, “I don't think that...such an issue could damage the Jewish community in Iran.” Ahmadinejad’s denials brought the subject to the fore in Iran in a way hitherto unseen. “The Holocaust has entered the Iranian psyche mostly since Ahmadinejad,” Sarshar says. “I myself hadn’t heard the word until I moved to the United States.” A California-based Jewish Iranian author, Ari Babaknia, published a multi-volume history of the Holocaust in Farsi in 2012.

Iran’s current president, Hassan Rouhani, has tried to salve the wounds Ahmadinejad opened, first by tweeting Rosh Hashanah greetings to Jews in September 2013, then by taking Jewish MP Moreh Sedgh to the United Nations General Assembly, and by condemning “whatever criminality [the Nazis] committed against the Jews.” Rouhani has had good relations with Iran’s Jewish leaders since his days as an aide to President Mohammed Khatami, says Sternfeld. But Sarshar sees Iran’s recent unveiling of a monument to Jews killed in the Iran-Iraq War as a move driven by contemporary political considerations. “Why it took a government — which used to rename streets on a daily basis after eight or nine-year-olds who walked onto mines and died — 29 years to erect one monument to all the Jews who died in the Iran-Iraq War, is worth contemplating.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments

The Iranian people may be the least antisemitic but their leaders are amongst the worst. The author whitewashes the twisted evil that is Ahmadinejad and senior leaders' call for Israel's annihilation and use of virulent antisemitic terms (insects, disease cancer when referring to Israel).