On August 15, Ali Jannati marked two years as Iran's minister of culture and Islamic guidance. Newly elected president Hassan Rouhani appointed him in August 2013, amid an atmosphere of post-election promises and hope for reform after eight years under former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

After his appointment, Jannati, who previously served as an ambassador, a member of the Revolutionary Guards, and deputy interior minister for political affairs, spoke out against cultural censorship under Ahmadinejad. "If the Koran hadn't been sent by God and we had handed it to book censors, they wouldn't have issued permission to publish it and would have argued that some of the words in it are against public virtue," he said of the culture ministry under the former president.

He indicated that the practice of prior censorship might come to an end, and certainly that the climate for publishing, the arts and free speech would improve.

Under Ahmadinejad, censorship was widely practiced, with censors making good use of the so-called “Control-F” method of censoring — looking for particular words or phrases that have been determined to violate the cultural, religious and political fabric of the Islamic Republic and deleting them.

Small Media’s James Marchant, the lead researcher of Writer's Block, a report that looks at censorship in Iran, says under Ahmadinejad, almost anything that could be deemed to go against Islamic law would be censored. “So that could be alcohol, parties, underground music, all these different arenas in which the Ahmadinejad government was trying to protect Iranian youth culture from western interventions and western influences,” Marchant says. “This was done in a really bizarre way sometimes. Gender segregation was enforced in Iranian literature to the extent that a married couple wouldn't be allowed to kiss or embrace in books, and even the word "kiss" itself could be censored. According to one anecdote in the report, a parent was supposed to kiss their child, and the censor went back to the author and asked them to change it to a hug, because a kiss from a parent to a child was a bit too risqué for them.”

Marchant says that although most writers remember publishing under Ahmadinejad as being horrendous and suffocating in terms of free expression, Iran’s own records on publications registered with Iran’s “Book House” during that period suggest a different story. “There was a really dramatic climb in publication figures under the later stages of the Ahmadinejad period,” Marchant says.

Marchant also describes how he spoke to Ali Aghar Ramezanpour, Deputy Culture Minister under President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), who was responsible for putting together the “Book House” database in the first place. It was at this point that a clear case of corruption emerged, he says. “Lots of publishers were just providing fake statistics to receive various subsidies from the government. It was very easy to falsify records, and there was a lot of economic opportunism from different parts of the state, and on the part of several publishers. Sometimes they would just take PhD theses from universities and print several hundred copies of them, and then enter them into this national library database as publications.” Ahmadinejad made it look as if Iran’s publishing industry was flourishing, but in reality, censorship was rife and what got published was extremely limited.

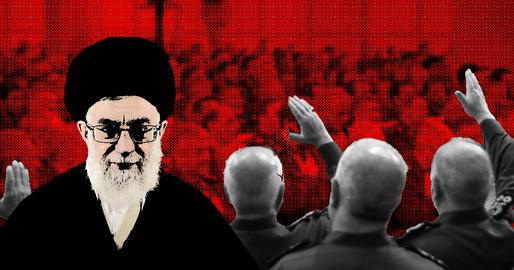

Hopes for More Freedom — and Hardliner Tactics

So how has Jannati fared in the last two years? How has he stood up to constant pressure from Iran’s formidable hardliners? And how far has been able to carry through on the promises he and President Rouhani made to the Iranian public back in 2013?

"With Rouhani in office, many sectors got high hopes for better conditions,” says Raha Zahedpour, an Iranian journalist and author based in London. “Iranian artists were among those that had good reasons to be optimistic. During the first six months, Jannati opened the house of cinema, which was shut down and sealed by Ahmadinejad's office, gave Cheshmeh Publishing House its license back, which had been revoked. So by undoing some of Ahmadinejad's wrongdoings, the cultural space felt more relaxed and some restrictions lifted.”

As culture minister, censorship is two-fold: not only does Jannati set out what government censors should look out for, but he has been subjected to a formidable censorship campaign himself, constantly attacked by hardliners who use culture as leverage for power whenever they can. It has been a tough two years.

On May 27, 2014, MPs publicly criticized Ali Jannati, spurred on by hardliner cleric Ayatollah Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi and the Islamic Stability Front, which tasks itself with protecting the values of the Islamic Republic. He was attacked for his policies, and for his stance on music in particular. And in January 2015, Islamic vigilantes and hardliner politicians and clerics lashed out at some sectors of Iran’s music industry, organizing protests against live music performances, including a rally in Bushehr against the folk group Lian and calls for greater restrictions on music in Shiraz. Following intense pressure, in July, the ministry’s head of music Piruz Arjmand resigned.

Amid the huge hopes for change that followed the 2013 election and Jannati’s appointment, Raha Zahedpour says Jannati, like Rouhani, made promises he could not keep, including putting an end to pre-publication licensing of books, which she said was impossible in the current “Islamic establishment.”

“The fact is, the cultural sector had a horrible and catastrophic era under Ahmadinejad,” Zahedpour says. Taking steps to fix some of that damage has essentially meant that Iran is now back where it started from before Ahmadinejad was president, she says.

Censorship Continues

Prior censorship continues — after all, it became rooted in Iran long before the revolution. Some argue that it is harder to publish potentially controversial material through censorship boards appointed by reformist governments. Instead of using the “Control-F” method of censorship so favored by the Culture Ministry under Ahmadinejad, censors under Rouhani are tuned into nuance, symbolism and metaphor, and so able to detect subversive content. Many of the writers Small Media spoke to said that censors working today are “more adept at censoring something that could be considered to be dangerous” for the regime”. The same can be said about censors who worked under the reformist Khatami government.

So what gets censored under Jannati?

“High-profile authors like Mahmoud Dowlatabadi still see their work banned from publication, and the ‘blacklist’ appears to still be in operation,” said Marchant. “There are still a number of red lines. Some of the people we’ve spoken to have mentioned things like sex, society — all kinds of social issues — as being quite divisive still. Sepideh Jodeyri, the translator for Blue is the Warmest Color [a French film], suffered a very extensive right-wing media campaign in the last couple of years as a result of her work. There are still social issues that serve as lightning rods to right-wing campaigners. In that respect, it’s not necessarily that much easier an environment for progressive and liberal authors to work within. Political themes still seem to be censored quite heavily. Dowlatabadi’s The Colonel still remains censored — a very political work of the last decade.”

Criticism of the Islamic Republic is also taboo, although Marchant says authors “can still slip through coded criticisms of the Islamic government as long as they phrase it in a flowery enough way that they won't be too offended.” But the fact that Rouhani employs “more intelligent censors” is also a problem: they know what to look for underneath the flowery language, and they know the tools people employ to circumvent censorship.

The battle to control music continues, and in many ways, it symbolizes the health of cultural freedom in Iran. Sensing that young Iranians were increasingly traveling outside Iran to attend pop music concerts, the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization of Tehran issued new guidelines for travelers ahead of the Nowruz holidays earlier this year. Calls for women to be allowed back on the stage continue, but even if Jannati wanted to push this ahead, many local Islamic Culture and Guidance officials disagree: in October 2014, the director-general for the Isfahan’s culture department said, “female musicians should stick to lullabies.”

But Zahedpour says there is reason for optimism, and Jannati has secured some positive results. Artists and others working in the cultural arena feel more hopeful, she says, if tentative. “The relationship between the ministry and the publishers is healing, and many books in the queue received their response and many of them have been published.” But the foundation of censorship is still enshrined in the culture. Censorship is less harsh, she says, but very much in force.

Marchant also takes a positive outlook, and says there are hopes for greater diversity in publishing and better distribution, and the rise of e-publishing offers a whole range of new opportunities.

Raha Zahedpour says Jannati “has shown good change is possible,” although she acknowledges that hardliners have made life difficult, putting Jannati under constant pressure. “He has been questioned by parliament twice in two years. Nonetheless, he tends to follow a more moderate path.”

Read Writer’s Block: The Story of Censorship in Iran by Small Media

Read the report in Persian

Related articles:

Culture Minister: “We stand by our decisions”

Ministry Speaks out Against Music Protests

To read more stories like this, sign up to our weekly email.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments