In 1988, Iran secretly executed thousands of prisoners, disposed of their bodies in unmarked mass graves, and forbade their families to mourn in public. Twenty-eight years later, the dead refuse to rest. In August, the office of the late Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri – who was once the heir apparent to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini – released a 1988 audiotape in which Montazeri called the killings “the biggest crime in the Islamic Republic.” Just this month, a political prisoner, Maryam Akbari-Monfared, filed a formal – if symbolic – complaint with Iran’s Justice Ministry over the killing of two of her siblings that year.

Outside Iran, legal experts discuss the 1988 executions in the context of “enforced disappearances” – a crime against humanity defined under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. “An enforced disappearance has three elements,” says lawyer Shadi Sadr, director of the human rights group Justice for Iran. “The first is that the person is arrested by agents of the state or those who are affiliated with the state. The second is that the state or state agents don't disclose the fate or whereabouts of the person. The third is that, by those acts, they put the person beyond the protection of the law, as if the person did not have any rights as a human being.”

Sadr, who spoke at a recent a London Metropolitan University event entitled Forced into Unbeing: Enforced Disappearances in Turkey and Iran, recognizes that the phenomenon is not specific to Iran. Panellists at the talk also addressed the enforced disappearance of Kurds in the course of Turkey’s long-running conflict with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK. And the international community, she points out, first took note of the phenomenon in South America. “Enforced disappearances as a state policy emerged during the dictatorships in Chile and Argentina in the 1970s. That was when the working group on enforced disappearances was established at the United Nations.”

How the 1988 Massacre Happened

In Iran, as in South America, many of the “disappeared” prisoners were leftists of various factions who opposed the government. The majority of those were members of a militant opposition group called the Mojahedin Khalq, or MEK, which combined Marxist and Islamist ideas with a personality cult surrounding its leader, Masoud Rajavi.

Before Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, the MEK had joined Khomeini’s supporters in their efforts to overthrow the shah. But as Khomeini seized power for himself and marginalized rival revolutionaries, the MEK carried out terrorist attacks against his Islamic government.

During the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, many MEK members sought refuge in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. In July 1988, MEK members based in Iraq participated in an Iraqi offensive against Iran but were defeated. Khomeini decided to take revenge by ordering the killing of people belonging to opposition groups who were already serving their prison sentences. Those prisoners who refused to display their loyalty to Khomeini before a specially-selected panel, or "death committee," were hanged in groups.

The context of the war — in which hundreds of thousands of people died on both sides — allowed the killings to go largely unmarked. “The international community failed in its responsibility to the victims of the 1988 massacres and the other mass atrocities that happened in the 1980s,” Sadr says. “The on-going war between Iraq and Iran was an international issue at that time, so few people cared about the internal matters, just as in recent years, fewer people have cared about human rights violations in Iran because of the nuclear issue.” International mechanisms for investigating enforced disappearances and crimes against humanity were also less developed at the time.

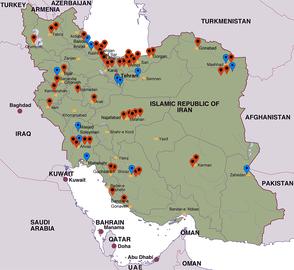

A Map of Skeletons

Today, few Iranians dare to openly discuss the killings inside Iran. “There are many reasons for this silence,” Sadr says. “First of all, the authorities who committed those crimes are still in power, and they have always justified those crimes. Within the domestic system, the perpetrators have never been brought to any sort of justice.”

Mostafa Pourmohammadi, the man Ayatollah Montazeri accused of playing the principle role in deciding which prisoners to execute, is now Iran’s justice minister. “There is complicity amongst the ruling class of the Islamic Republic, whether they are reformist or conservative,” Sadr says. “They all stand against any kind of accountability because they want to protect their place in the spectrum of power.”

While Iran is dotted with gravesites connected to the killings, they remain unmarked and largely unvisited. “One of my personal regrets is that when I was in Iran, I never visited any of the mass graves,” says Sadr, who left Iran in 2009.

But now, her organization, Justice for Iran, is working to identify as many of the gravesites as possible, and to present the sites on an “underground map.” “In our primary research, we identified 65 places that are allegedly the sites of mass graves,” she says. “So far, we have just been able to confirm 11 places of mass graves out of 65 alleged sites. We have very limited resources for this research, and it is progressing slowly.”

It can take decades for a country in which authorities have carried out enforced disappearances to find the political will to re-examine its history. Sadr cites the example of Spain, which also experienced mass executions during the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War and the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. “In Spain, the whole social discussion about past atrocities started because of discussions about some graves in villages. The families of the victims were only able to get an official explanation after 70 years when the state set aside a budget to open up the graves. Despite the fact that the contexts of Spain and Iran are very different, this could be the case in Iran as well.”

A Different Iran

In the meantime, Sadr suggests, Iranian civil society can play a role. “Having talked about my own experience in Iran, I cannot tell Iranian citizens to visit all of those mass graves I didn’t visit. But if I want to speak about civic responsibility or citizens' responsibility, it would be to at least accompany the victims’ family members when they go to visit a mass grave, and to try hard to preserve those graves. Just being with those families and listening to them would be the least one could do."

Ultimately, Iran’s ability to face up to the mass executions of 1988 will determine what kind of country it becomes. “The skeletons in these graves could change the future,” Sadr says. “I don't think any genuine change can happen in Iranian society without coming to terms with past crimes, and without having a shared historical memory about what happened in the 1980s. All of the human rights violations we are seeing now have their roots in the first decade after the revolution. Without resolving them, we cannot move forward and have a better society.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments