The verdict in a massive corruption case involving the Iran Petrochemical Commercial Company (PCC) was announced on September 5, 2021. But nearly three years after proceedings first got under way, the details remained shrouded in mystery.

We were told at the time that 15 named defendants had been sentenced to a total of 180 years in prison, linked to the embezzlement of around 6.6bn euros. But curiously for Iran, none of them were in custody at the time the sentences were issued. Most were out on bail, and a handful had even managed to leave the country.

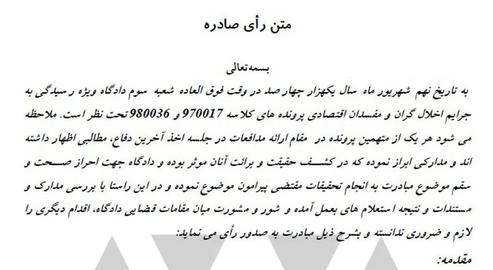

IranWire has now gained access to the 2,000-page judgment, issued by Judge Asadollah Masoudi-Magham in Branch 3 of the Special Corruption Court. The contents shed light on the sheer extent of mafiosi behavior, graft, cronyism and money laundering in Iran’s still-lucrative petrochemical industry – and on how far the 15 convicted parties were aided and abetted by dozens of others, many in positions of power.

Out of necessity rather than choice, due to the document’s sheer size, we’ll be laying out the background and contents in instalments over the next few weeks. This first article gives some idea of the number of players involved in the PCC fraud, and how some of them evaded justice.

***

What do we Know About the PCC?

The Iran Petrochemical Commercial Company was established in July 1990, 21 years after the Islamic Revolution. It is the semi-public, commercial arm of the government-owned National Petroleum Company, responsible for brokering the sale of all Iranian petrochemical products abroad. The firm also arranges the sale of goods, services and logistics to Iranian oil and gas complexes.

On December 29, 2009, some 55 percent of shares in the company were supposedly transferred to the private sector, with its new majority owner being the Iran Investment Company. This meant the PCC was officially no longer a state-owned enterprise; it duly now describes itself as “independent” on its website.

In reality though, this “privatization” was of a type particular to the Islamic Republic. For many years now, especially since the Ahmadinejad era, companies in Iran have passed out of formal government ownership but into the hands of individuals and entities that cannot be considered “private” in the truest sense of the word.

Examples of major parastatal company owners are the Martyrs Foundation and the Mostazafan Foundation, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and regime-affiliated conglomerates directed by current and former politicians. These manoeuvres relieve companies of their obligations – for example, to file public accounts – while keeping them under a measure of state control. The PCC was no exception. And even as the scandal was unfolding, its parent company was continuously listed as one of the top 100 Iranian companies from 2011 to 2013.

How Did the Swindle Work?

The final charges brought against the 15 related to illicit activities between 2009 and 2013 that were said to have cheated Iranian oil and gas firms out of a cumulative $6.6bn. Using a network of shell companies on the pretext of “bypassing sanctions”, the directors were said to have deliberately failed to return a vast amount of foreign currency to Iran.

Instead, they either invested the bulk of the money in third-party enterprises abroad – sometimes using their own names, or else the names of trusted confidantes – or covertly converted it to rials on the open market. They would then pay back domestic oil and gas firms based on the officially-set price of foreign currency in Iran, which is considerably less than the open-market rate.

The verdict seen by IranWire summed up the scam as follows: “[The Company’s official] role was that off a commissioned contractor which was to receive Iranian petrochemical products, sell them [abroad] and, after deducting its own commission, hand the proceeds back to the original companies. In practice, however, the money in foreign currencies was either converted to rials on the open market, generating huge profits from the difference between the official and the open market currency rates, or was invested in various places.”

Cases Dropped Against More Than 100 Co-Conspirators

The verdict confirms that this huge corruption case was not, and could not have been, the work of a handful of bad actors, operating alone. On the contrary: the 15 were aided and abetted by a vast network of individuals and government institutions, with the Islamic Republic’s own intelligence and security agencies playing a decisive role in the affair.

We learn that the original indictment featured the names of 129 suspects who were said to be involved in the fraud, as well as an array of legal entities. But the public prosecutor’s office of Branch 6 of Tehran’s General and Revolutionary Court only allowed cases to be progressed against 29 of them.

In the end, only a token 15 were convicted and publicly named. In all likelihood due to political pressure, the names of the others were excised from the public record. In the course of three years, the list of alleged culprits had been whittled down to just over a dozen figures on whom the blame could comfortably be pinned. The same pattern has been observed in previous grand corruption cases in Iran. Here, perhaps the best-known of the final set was Mahmoud Reza Khavari, the former chairman of Melli Bank, who has been living as a fugitive in Canada since news of a three trillion-toman bank fraud in Iran broke in 2011.

The Unnamed ‘Accomplices’

The 2,000-page judgment names a constellation of individuals who were initially charged in connection with the PCC fraud, but against whom charges were eventually dropped in pre-trial proceedings. Perhaps the most famous is Ali Naghi Khamoushi, the first head of the Mostazafan Foundation and a godfather of the petrochemical mafia in Iran. Also named in the judgment is his nephew, Abolhassan Khamoushi.

Khamoushi Senior was the CEO of Iran Investment Company, the PCC’s parent company after 2009, which was formed during the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. He became the main shareholder of a multitude of development and energy companies during Iran’s skewed “privatization” drive in the 2000s and early 2010s.

His nephew, Abolhassan Khamoushi, then became chairman of the board at Iran Investment Company. He was also chairman of its disgraced subsidiary, the PCC, at the time the Iranian oil and gas firms’ money was being embezzled.

Jalil Sobhani, who was then the CEO of Petrochemical Industries Part, Equipment and Chemicals Engineering Company (SPEC) and a shareholder of Iran Investment Company, was also initially indicted but removed from proceedings ahead of the trial.

The children of some of the 15 main defendants, including Mohsen Amadian and Mohammad Hossein Shir-Ali, were also on the original list. In Iran it is not unusual for oil and gas barons to bring their children into business: either in name only, for the sake of paperwork, or with some actual function attached. In the case of Amadian and Shir-Ali’s sons, the reason for the charges against them being dropped was not specified.

Finally and most notably, the judgment names several members of Iran’s intelligence and security establishment who were among the accused when the case was first opened, but later let off. They include, but are not limited to:

- Siamak Nazarinejad, known as Sajjad, the Intelligence Ministry’s representative to Iran’s petrochemical industry;

- Seyed Mansour Saleh Ebrahimi, an employee of the Intelligence Ministry;

- Seyed Reza Bagheri, director-general of the Intelligence Ministry’s Bureau of Fuel, Energy and Economic Affairs;

- Rasoul Lahijanian, a terminated employee of the Intelligence Ministry;

- Masoud Forouzandeh, a terminated employee of the Intelligence Ministry;

- Naser Enayati, chief inspector of Iran’s General Inspection Office for the National Petrochemical Company and its affiliates;

- Majid Tajdari, an employee of the General Inspection Office.

Mohammad Reza Nematzadeh, a four-time cabinet minister, is also listed among those who were charged at first but never prosecuted.

Natural persons aside, the list also features tens of companies and legal entities that for whatever reason were never formally investigated. The main one, of course, was Iran Investment Company, but the list also includes MTN Irancell: a widely-used network provider in Iran founded in 2005 as a joint venture between the South African MTN Group and Iran’s Electronic Development Company. The majority of MTN Irancell’s shares are owned jointly by the Mostazafan Foundation and the armed forces of the Islamic Republic.

The judgment states that Alireza Ghalambor Dezfuli, Irancell’s CEO at the time, Nazir Patel, chief financial officer of the MTN Group, Ferdinand Moolman, chief operating officer of MTN Group at Irancell, and Ebrahim Mahmoudzadeh, chairman of Irancell’s board of directors, were investigated as part of the case but not formally indicted.

Another apparent key player who evaded scrutiny was Khalil Khalilzadeh, then chairman of Iran’s Credit Institute for Development.

Verdict Reveals Extent of Cover-Up

The verdict received by IranWire is explicit and withering in its description of how powerful actors in the Iranian establishment, including the intelligence and security agencies, worked to help some members of the conspiracy evade justice.

In one section, the judge refers to a letter dated August 4, 2013, sent from the internal security department of the IRGC’s Intelligence Unit to counterparts in the Intelligence Ministry, alerting them to the fact that some of the Ministry’s employees were among the suspects in the PCC fraud. Not only did the Ministry not look into the matter, we read, but it completely ignored the warning.

Separately, Page 9 of the first section of the judgment states: “By obtaining the support of certain officials in various areas that were responsible for holding them accountable, [the accused] built a cordon sanitaire around themselves. And by using various threats, they removed anyone in their path who wanted to fight their corruption, and to report it to the proper authorities.

“But they did not stop here. Members of the PCC board and a number of major shareholders, some of whom are the main defendants in this case, took action to destroy company information by transferring and dismissing people who held the information.”

On Page 10, we then read: “Certain officials who have encountered the insistence of this court on stablishing the truth have promised some of the accused that they will resolve their cases through branches of the National Supreme Court [instead of the Corruption Court].

“Some of the very wealthy and influential main defendants, who had numerous meetings with officials, did their best to threaten and defame this court’s judges in order to get their cases shelved. Many times during the proceedings, they asked for help from officials to pervert the course of justice.

“When the court resisted, they arranged for the escape of defendants, such as Messrs. Mehdi Sharifi Niknafs [the now-convicted former executive director of the PCC] and Ashraf Riahi [son-in-law of former Industries Minister Mohammad-Reza Nematzadeh] and... forced Mr. Ashraf Riahi to make false statements to the BBC. He was in possession of valuable information about another defendant in the case but this way, he could no longer offer it [to the court].”

Judge Demoted After Damning Verdict

The presiding judge, Asadollah Masoudi-Magham, was born in Tehran in 1968. In recent years he has overseen such high-profile cases as the Sarmayeh Bank scandal, where (in)famous defendants included Hossein Hedayati, a business tycoon, Parviz Kazemi, a former minister under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Mohammad Hadi Razavi, a son-in-law of President Rouhani’s Minister of Labor, and Mohammad Emami, a TV producer.

In 2019, while he was serving as the presiding judge at Branch 3 of the Special Corruption Court, Masoudi was also made head of Special Joint Tribunal for Investigations into Corruption. But just a few weeks after he issued this verdict on the PCC fraud, he was removed from post and transferred to the National Supreme Court to preside over appeals: an effective, major demotion.

Judge Masoudi-Magham himself has said on the record: “In important cases, I have been repeatedly threatened by the government and parliament.”

***

All of the above gives just the barest overview of the level of top-level interference in this gargantuan corruption case: one the Iranian public was deprived of the chance to observe. In upcoming reports we will delve into significant aspects of the PCC fraud, and the actions some of its major players. Amongst a great many others, they include the Intelligence Ministry, the IRGC’s Khatam-al-Anbiya Construction Headquarters, the General Inspection office, Irancell, two Ahmadinejad-era cabinet ministers, former president Hassan Rouhani, and the current President of Iran, Ebrahim Raisi.

Related Coverage:

Who's the Mysterious Survivor of Two Grand Corruption Cases in Iran?

From Luxury Villas to Defrauded Banks: The Mother of All Corruption Cases Gets Under Way in Iran

Government Report Reveals More Corrupt Privatization Practices in Iran

Corrupt to the Core: The Long List of Corrupt Iranian Officials

Sanctions on Iran’s Petrochemical Products: A Heavy Blow to the Economy

How the Corruption Mafia Took $30 Billion out of Iran in One Year

The IRGC Commercial and Financial Institutions: Khatam-al-Anbiya Construction Headquarters

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments