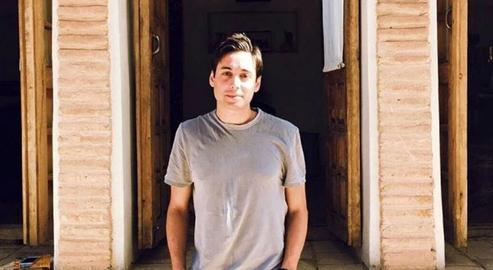

The journalist Kianoosh Sanjari (Mehdi Sanjaribaf) left Iran on Monday, March 21: the first day of the Iranian new year. Formerly based in the US, he had returned to Iran in autumn 2016 out of homesickness and love for his country, only to be rearrested, tortured and jailed for being a “spy” in a sham trial lasting barely 10 minutes. He has spoken out about the ill-treatment he and others received several times over the years, but remained under a travel ban until the weekend. After boarding the plane, he sent IranWire this detailed account of how the last half-decade has affected him.

***

Tonight, March 21, 2022, I passed through the last airport gate with hesitant steps, tear-filled eyes and an aching heart. I boarded the plane and left my dear, occupied homeland behind after five years, five months and 20 days of prison, psychiatric hospitals, being interrogated in “safe houses”, signing the attendance roster every week on medical leave, the payment of fines (a ransom), and the lifting of the travel ban.

A Moment of Weakness

For those who are not familiar with my story, let me just say that I was madly in love with my country. So on October 2, 2016, after 10 years of working and living in the United States, I decided to overcome once and for all my deadly homesickness – for my family and my country – and the terror of returning to a land where, before escaping, I had faced torture, solitary confinement and prison sentences several times.

Despite my madness, I knew my country was still occupied by the devil. I had experienced the pain of being a stranger in my own country before, and I knew the Intelligence Ministry, the IRGC Intelligence Unit, the Revolutionary Courts and judges like Salavati ruled over the lives of ordinary people. But I was so gripped with this madness, I wanted to hope that “humanity” would rescue me. I forgot the truth, that at this juncture of my country’s history, the ability to comprehend this lofty ideal has been uprooted.

What They Did to Me

Let me tell you this. Despite every horrible thing that they did to me, I wanted to go on living in my country. But the occupiers did everything they could to change my mind.

After my conditional release from prison (based on Article 522 of the Islamic Penal Code, and after my forced hospitalizations on a psychiatric ward — a new project by the security establishment to portray political opposition as insane), I continued to live in isolation. I found a job with an advertising agency, but a short while later, my employers told me: “They came here, and they want you out.”

I fell in love with a girl and entertained beautiful dreams. But soon enough they came to talk to her father, scared him by telling him I was a “saboteur”, and he broke off the relationship.

After I was given the medical leave of absence, for two years I was forced to go every week to the office of Amin Vaziri, head of Evin Prison’s Security Prisoners’ Administration, sign the roster and pledge to go there next week as well.

The two years of my life outside prison were spent under the Damocles sword of the fear of going back to prison. Nine times, both before and after I was sentenced, I was summoned to the Intelligence Ministry’s safe house on Golnabi Streer (next to Hosseinyeh Ershad) and interrogated about details of my life, my family, my job, my personal relationships, my friends, and relationships that I did not have. All this happened after I had rejected their every demand to cooperate with them. In a report to Branch 26 of the Revolutionary Court, they had nothing favorable to say about me, even though I had come back to my country voluntarily. They wrote that I deserved no extenuation because I was not cooperating with them.

They had wanted me to work with the Intelligence Ministry in three areas if I didn’t want to serve my prison sentence: to report on the activities of the opposition and journalists, to communicate with my friends and others in the opposition, and to gather and deliver information. I refused. Then they wanted me to at least take part, along with my mother, in a television interview for the 20:30 news program in a park. But I refused this as well.

A Farcical Arrest and Trial

My arrest resembled a kidnapping. I was in cab and as the other passengers were getting out, two young men entered, handcuffed me, pulled me out of the cab, pushed my head down and threw me into their own car. When the car started moving, they handed me my arrest warrant from Branch 1 of Evin Courthouse. The agent sitting next to me turned on his camera and filmed me as I was reading it.

Right outside Evin Prison, before entering the compound, the interrogator came into the car and asked me a few questions. Then they took me directly to the Ministry’s Ward 209, had me wear the detention center’s uniform, gave me two blankets, and showed me my cell. I put the blankets in the cell and was immediately taken to another room where the questioning started as soon as I went in.

After a few months, they took me to the last floor of the prison education center (school), got me to wear my own clothes, and sat me in front of a camera. The interrogators were sitting on one side of the room, and two young men asking me questions were in front of me, next to the camera. In that interview, I explained how since adolescence I’d been curious about injustice and dictatorship in Iran, how my youth was wasted in revolutionary courts and prisons, why I left Iran and why I returned. It seemed they were not happy with that interview.

After I was released from Ward 209, I got regular phone calls summoning me to the Intelligence Ministry’s safe house. The last time I went there, before the trial, an apparently high-level official came and once again officially asked me to cooperate with the Ministry. He said my prison sentence would not be executed if I did. Once again I said no.

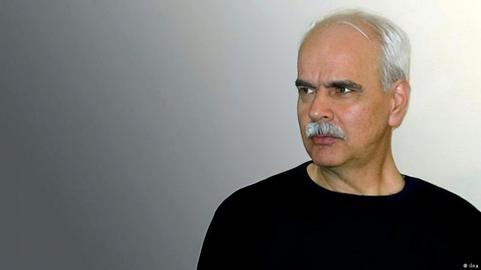

A few days later my trial took place at Branch 26 of the Revolutionary Court. That day, I was in court all by myself. The trial was a formality, a sham lasting no more than a few minutes, although there was a recess; Judge Mashallah Ahmadzadeh left the courtroom and they took me out as well. A few minutes later Judge Salavati, accompanied by two bodyguards, entered. They called me back in too.

Ahmadzadeh opened a file on the desk and read a few lines of reports I had written for VoA and Iran Human Rights, about were about violations of human rights in Iran and interviews with the families of anti-government protesters who had been killed. Without referring to any charge that could have had anything to do with those reports, Judge Salavati turned to me and said I had come to Iran to as “an informant” and “a spy”. Then he stood up and went away.

So, in a trial that lasted no more than 10 minutes, I was sentenced to 11 years in prison (five years’ minimum based on Article 134) and a two-year ban from leaving Iran, based on Articles 499, 500 and 610 [of the Islamic penal code]. Without any clear or specific evidence I was convicted on three counts: “collusion and conspiracy to commit crimes against national security”, “propaganda against the sacred regime of the Islamic Republic of Iran” and “membership of an illegal group.”

Branch 36 of the Revolutionary Court of Appeals presided by Judge Zargar, upheld everything in this verdict, which that was requested by President Rouhani’s Intelligence Ministry.

Intimidation and Harassment Outside Prison

I tolerated all the difficulties of the past five years, fought back and lived on hope, whether I was in solitary confinement on Ward 209 for the third time or during that one week when my hands and feet were handcuffed to the bedposts in Aminabad Psychiatric Hospital, when I reflected on how I was living the most horrifying days of my life in my own homeland. This was true even later, when I was hospitalized next to the most distraught psychiatric patients and subjected to electroshock therapy. Yes, nine times they used electroshock therapy on me. They’d anaesthetize me and give an electric shock to my brain so as to wipe my memories. They were wiped out, but only for a few days. Each time I triumphed over the nightmare through my faith in justice, regained my hope in life, and returned to life with indescribable joy.

A Stolen Youth

During the time that I was on medical leave I considered it my moral duty as a human being to speak to the free media and warn them against claims by the Islamic Republic officials that Iranians can safely come back to Iran. I notified them that they might meet the same fate as me. For this, and for defending the rights of other political prisoners, my freedom was delayed.

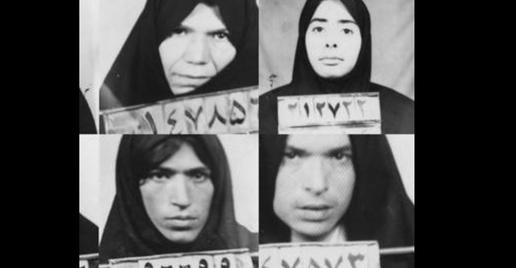

I knew I wouldn’t be brave enough to withstand these threats, the intimidation and the weekly summonses for the rest of my life. From the ages of 17 to 24, my life had been spent under these pressures. I’d spent the next 10 years away from my home while I thought about my country day and night. Then, up until today, I’d spent another six years of my life in prison or at risk. As a journalist and a human rights activist, I’d been jailed under the presidencies of Khatami, Ahmadinejad and Rouhani. One year of these last six years was spent in solitary confinement in the detention centers of Towhid [the Anti-Sabotage Joint Committee], the Revolutionary Guards’ Ward 2A, Evin’s Ward 240 and the Ministry’s Ward 209.

The Islamic Republic ruined the days of my youth, as it did to millions of others. Days that could have been filled with passion, happiness and sweetness were spent in prison, doing irreversible damage to my body and my soul.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments