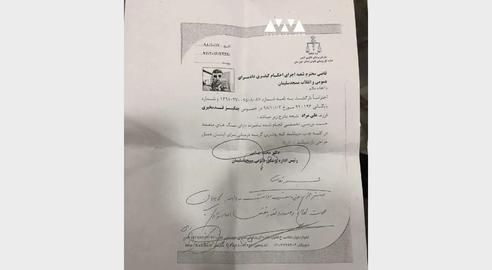

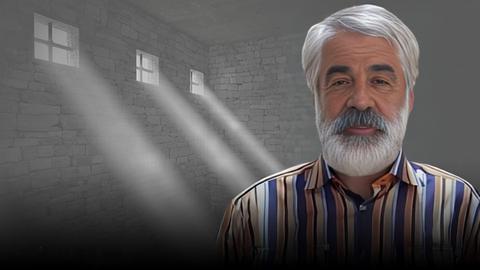

For the past 11 years, activist Changiz Ghadam-Kheiri has been inside one of three prisons: Sanandaj, the capital of Iranian Kurdistan, and Masjed Soleiman and Ahvaz in Khuzestan. He was arrested on June 9, 2011 along with a number of other Kurdish citizens and charged with moharebeh (“war against God”) for membership of the Komala Party of Iranian Kurdistan. The Revolutionary Court of Sanandaj, presided over by Judge Hassan Babaei, later sentenced him to 40 years in prison.

In February 2022, Saleh Nikbakht, a human rights lawyer, managed to secure Ghadam-Kheiri medical leave in exchange for a substantial bail. He never returned. Here at last is just part of his story, in his own words.

***

“The interrogator kicked and punched me where my injury was. He’d push his ballpoint pen into the wound, saying, ‘It doesn’t matter to us whether you live or die, because everybody thinks you’re already dead.’

“When I was arrested, the bullet had hit my side and destroyed my left kidney. For a full day and night I was blindfolded and cuffed, and shackled to the flagpole in the compound of the IRGC Intelligence Unit in Sanandaj. The next day, when they took me to hospital, the interrogator ordered the doctor just to stitch up the wound.”

Changiz Ghadam-Kheiri is now 33 years old and a native of Hendiman village in Kamyaran country, Iranian Kurdistan. In June 2011 he was arrested by the IRGC alongside Mohammad Hossein Rezaei, Fakhreddin Faraji and Ayyub Asadi. The bullet that struck him is still lodged in his body today.

Doctors at the Towhid Hospital had wanted to give him surgery, but had to make do with stitching up the wound as commanded. Two days later Ghadam-Kheiri was taken back to the detention center. “For 12 days straight,” he told IranWire, “I was interrogated with my hands and feet tied to the bed. They wouldn’t even let me take off the blindfold.

“I felt that, in one way or another, everybody there was a torturer. Even the person who changed my bandages did it in such a way that it caused excruciating pain. Despite the severe pain I was in, through four months of nonstop interrogations, they never gave me a single painkiller.” The sessions would begin early in the morning, he added, and went on until he couldn’t talk anymore.

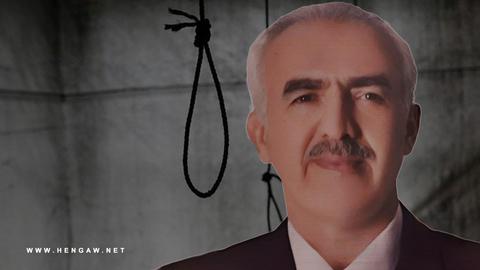

One of the questioners kept telling Ghadam-Kheiri to confess instead to “terrorism” and “armed activities against the regime”, he said, so that he could appeal for a reduced sentence.

Going Head to Head With PressTV’s Interrogator-Journalists

Three months and 20 days into his detention, Ghadam-Kheiri was forced to confess in front of a camera for PressTV at Kamyaran’s Intelligence Bureau. A man who introduced himself as Haji Rahimi told him he was the bureau chief as he removed the blindfold. Two PressTV reporters sat before him, holding the pre-written script for the interview. One of the fabricated points was that Ghadam-Kheiri had been dispatched by Komala from Iraqi Kurdistan to Sanandaj to commit acts of terror.

This, the political prisoner said, he totally denied. “When I rejected the charge, the PressTV reporter told me angrily: ‘If you don’t want to be executed you’ve got to read this text to the camera, exactly as it is here.’ But I only accepted that I was a member of Komala and had come back to Iran for political ‘propaganda; activities.

“The interview turned into an altercation. I believe they only broadcast two minutes of it. Because I hadn’t said what they wanted, both of the PressTV reporters kept shouting at me: ‘You totally deserve to be hanged.’” The Intelligence Bureau even hauled his family to the building to read out the part he denied.

Masjed Soleiman Prison: Hunger, Mismanagement and Covid-19

Ghadam-Kheiri was then convicted on the false charges and spent 18 months in Sanandaj Central Prison. In early 2013, he was internally exiled to a prison in Masjed Soleiman, 500 kilometers from his native village, without his family being informed.

This facility, he told IranWire, was a small one with just three wards holding around 200 inmates each, most convicted of ordinary and drug-related offences. His ward was in a basement seven steps down from the prison yard, with just 60 beds for a group of men numbering three times that.

“Some were forced to sleep in the narrow corridor,” he said. “There were just three bathrooms for 200 inmates. After coronavirus broke out on the ward, 10 of the inmates lost their lives, and nobody heard a thing about it. You weren’t just tortured the way the interrogators did it, but you were tortured every day by living in these conditions.”

Food provision, a prisoner’s basic right, was also pathetic, he said: “Just imagine it: they boiled around five or six kilos of beans with fried onions and water for 200 people on the ward. If it wasn’t enough, they’d pour some boiling water into the pot so that it would supposedly cater for everyone.”

Ghadam-Kheiri said that after the transfer, he once again requested proper treatment for his kidney. But even though Khuzestan’s official prisons medical examiner recommended it, as well as the hospital doctors, a Revolutionary Court judge refused to allow him to get surgery – seemingly under pressure from Kamyaran Intelligence Bureau. As a result, he went on hunger strike twice in Masjed Soleiman, in 2017 and 2018.

Finally, after five years of incarceration, Ghadam-Kheiri was granted medical leave. But the full 10 days of his furlough was spent getting X-rays and examinations, and the judge refused to extend it.

When pressed further, the judge eventually had him transferred to Sheyban Prison in Ahvaz for surgery. He waited there for nine months, but nothing happened. When he protested, the prison warden there told him: “They have been playing with you.”

A few days after this exchange, Ghadam-Kheiri was returned to Masjed Soleiman. Throughout this period, his family had been trying fruitlessly to secure him medical leave; officials had given them a phone number to call, but each time they did so, they either received promises that failed to materialize or were told he needed to “cooperate” first.

In any prison where inmates are not separated by category of crime, violent clashes are inevitable. Ghadam-Kheiri told IranWire that on one occasion he was attacked by two common criminals, but when he spoke to the warden, Ghasem Jamshidi, about it, he was told nothing could be done because he was not “cooperating” with the Intelligence Bureau. “Everything,” Jamshidi told him, “is quid pro quo.”

He was not allowed to use the library at Masjid Soleiman, or other prison services. This state of affairs continued until 2020, when he got a kidney infection and could no longer get to the bathroom without cellmates’ help due to the excruciating pain. He told IranWire that at this point, “I had lost all hope in life.”

A Window of Opportunity

Earlier this year, Ghadam-Kheiri’s lawyer Saleh Nikbakht submitted another request for medical leave on his behalf to the Revolutionary Court in Sanandaj. The case was transferred there and given to a new judge, Hossein Saeedi. On March 1, Saeedi granted him a month, on the condition that he post bail of one billion tomans [close to $135,000], to get surgery at a Justice Department-supervised hospital. He could also spend three days with his family.

Ghadam-Kheiri seized the opportunity to escape. Had he remained in Iran, he said, he would have been forced to endure the same treatment, potentially for another 29 years, with his family harassed all the while. He made his way straight to Iraqi Kurdistan and asked for asylum.

Now, Ghadam-Kheiri is living as a refugee across the border. This has come with its own problems; Kamyaran’s Intelligence Bureau has already begun to pressure and even build cases against some of those who posted bail for him.

“Now,” he told IranWire, “after 11 years of resistance and the most unspeakable pain, I believe my main goal is to defend my fellow prisoners regardless of their ideological affiliations.”

comments