Two young Iranian men, Mohsen Shekari and Majid Reza Rahnavard, have recently been executed by hanging on the charge of moharebeh, or “waging war against God”, over their involvement in the ongoing wave of nationwide protests.

Other defendants such as Hamid Ghareh Hassanlou, Saman (Yasin) Seidi and Mahan Sedarat have been sentenced to death on the same charge and for allegedly spreading “corruption on Earth”, which also carries a death sentence.

The hasty trials and executions of Shekari and Rahnavard raised many questions among the public, including whether death sentences can be handed and executed so quickly -- Rahnavard was hanged two days after his death sentence was issued and two weeks after the start of his trial -- and whether protesters can rightfully face charges punishable by death. IranWire asked two legal experts their opinions on these matters.

What “waging war against God” means

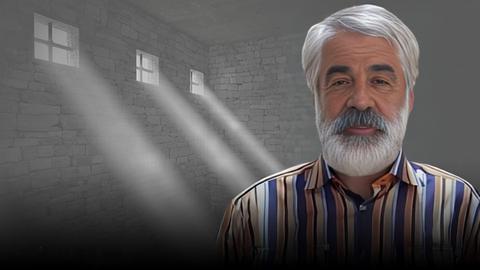

Human rights lawyer and Iran legal expert Hossein Raeesi explains that the structure of the Islamic Republic’s penal code is based on the Islamic jurisprudence and Shia fiqh -- the interpretation of jurisprudence. In the Islamic penal code, crimes fall into four categories: hudud (plural of Hadd, “boundary”), qisas (retaliation in kind), diyat (plural of diya, compensation or blood money) and ta'zirat (plural of ta'zir, punishment left to the discretion of the judge).

According to Raeesi, “waging war against God” and “corruption on Earth” fall into the category of hudud, meaning that the lawbreaker has violated a “boundary” specified by Sharia.

Hudud are actions that have been designated as crimes in the Quran or in early Islamic texts. “Waging war against God” and “corruption on Earth” are specified in the Quran and, therefore, are considered Haqq Allah or “the right of God”, meaning that they do not fall into public or private domain.

“Public crimes” hurt society while “private crimes” affect individuals. However, hudud actions do not fall into these categories; in other words, God is effectively the plaintiff.

Moharebeh and “corruption on Earth” can be forgiven?

Raeesi explains that crimes such as adultery, sodomy, thefts punishable by amputation of hand, drinking alcohol, moharebeh and corruption on earth are fundamental concepts of Islamic jurisprudence and cannot be changed.

According to him, if a court proves that a hadd crime has been committed, whether the plaintiff forgives the convict makes no difference. The punishment can be changed only if the convict repents and asks for a pardon, and if the vali-ye faqih (the Guardian Jurist, currently Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei) or his representative (the head of Iran’s judiciary) grants this pardon.

This point is important because in recent days it was reported that families of some of the protesters on trial for allegedly “waging war against God”, including Sedarat’s family, have secured the forgiveness of private plaintiffs. This has not changed the verdicts against the accused. But Raeesi says that even though the plaintiffs’ forgiveness cannot result in the charge of Moharebeh being dropped, it should at least provide an opportunity for appeal and pardon.

Moharebeh and “corruption on Earth” apply to protesters?

Immediately after Shekari’s execution, the question of whether protesters are mohareb or not was raised in the media, and some domestic media outlets published the views of religious authorities who disagreed with the verdict.

Mohammad Ali Ayazi, a senior member of the Assembly of Qom Seminary Scholars and Researchers, told ILNA news agency: “It is not right that agents prevent somebody from protesting when he has the right to protest against the existing situation, and then accuse him of moharebeh when he wants to defend his right.”

In Shia jurisprudence, moharebeh applies when someone terrorizes people with weapons, Raeesi said, adding, “None of the protesters threatened people’s safety, and in some cases their behavior was approved by the people.”

“In no way this can be construed as moharebeh. Even when a [member of the paramilitary Basij force] was killed, people were not terrorized because that Basiji was aiming his gun at the people. When somebody aims his gun at the people and wants to kill them, defending the people is the duty of a witness who believes that people’s lives are in danger. Therefore, if a Basiji is armed and can kill people, preventing him from doing so is in no way moharebeh. In certain situations, we can say that it’s not even a crime.”

On November 3, 16 protesters allegedly surrounded a Basij member and attacked him with knives and stones, which resulted in his death. On December 6, it was reported that five of the alleged attackers have been sentenced to death for “corruption on Earth.” The accused should have been charged with murder, according to Raeesi.

Proving “waging war against God”

Raeesi says moharebeh can be proven if the defendant confesses to the judge, but there are conditions that must be met for this confession to be considered valid. The first and the foremost condition is that the defendant must be aware of the punishments envisaged for moharebeh under Sharia law. These punishments include death, amputation of the right hand and the left foot, crucifixion until death and exile.

However, the expert points out that the Islamic Republic has changed “exile” into “exile in prison,” whereas exile literally means living in some other place, not in some other prison.

For the confession to be valid, it must also be delivered in the presence of a lawyer designated by the defendant himself. Raeesi points out that none of the alleged confessions in the recent moharebeh cases were given to the judge, but to interrogators or examining magistrates under duress and involuntarily.

From Torture to lack of evidence

Shekari did not do anything to terrorize people and did not kill anybody. Furthermore, he was not represented by a lawyer of his choice.

Rahnavard did not have his own lawyer either, was visibly beaten and tortured in custody and was not informed of the consequences of his confession. The only evidence against him presented in court was a CCTV video of an assault on security forces in which the attacker is not identifiable.

Sedarat did not confess in court and denied he had been armed. He told the court he was planning to peacefully gather with other people and chant slogans, and when security forces on motorcycles confronted him, he got into a fight with them.

Seidi was not assisted by his own lawyer and the public defender assigned to him was not given access to his file. He was sentenced to death for shooting a gun in the air and “gathering and colluding to commit crimes against national security.” His lawyer said the authorities had not found any gun in Seidi’s possession.

Hassanlou, who was also denied a lawyer of his own choice, made no confession at his trial, and no firm evidence was presented against him. In a forced confession, his wife claimed he had been involved in the killing of a Basij member. She later retracted what she said.

Raeesi says that under the law, the charge of “corruption on Earth” only applies to people who have committed many criminal actions, which does not apply the protesters currently on trial. He also emphasizes that none of the defendants have confessed to a judge, have confessed voluntarily or have been aware of the consequences of such confessions.

Pulling a gun doesn’t necessarily mean moharebeh

Many Iranians have recently discussed on social media previous cases related to a defendant who had assaulted people with weapons or committed killings. One of the cases mentioned was the 2000 assassination attempt against Saeed Hajjarian, a former reformist member of the Tehran City Council, by Saeed Asgar, a young man who was reported to be a member of the Basij militia. Hajjarian was paralyzed for life after being shot in the face. Asgar was sentenced to 15 years in prison but was pardoned and released within less than a year.

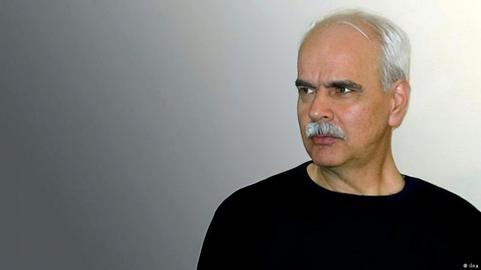

Mohammad Olyaeifard, a member of the International Association of Lawyers, tells IranWire that Asgar was not charged with moharebeh because, according to the law defining this offense, pulling a gun on specific individuals is not considered “waging war against God.”

In 2002, a group of six Basij vigilantes killed three men and two women in the city of Kerman for allegedly having illicit sexual relationships. The six were sentenced to death, but the sentences were rescinded after the families of the victims forgave the killers. This was made possible because the accused were not indicted with moharebeh.

Some social media have asked why none of the killers faced this charge. Olyaeifard says moharebeh did not apply because the killers targeted specific individuals who they considered as being corrupt, and killing them was a religious duty. The lawyer says that, according to the laws of the Islamic Republic, if the murderer can prove that his victim is Madhur al-Dam (a person whose blood is void) or that he genuinely believed so, he is not punished in kind and has only to pay blood money.

Hasty executions violate the rights of the convicts

Even if assumed that the protesters who have been recently charged with moharebeh and “waging war against God” have been lawfully sentenced to death, there is no doubt that their hasty executions are a violation of their legal rights.

According to Raeesi, in all cases punishable by death, the defendant must be able to appeal the sentence at least once and ask for a pardon: “This is part of the Islamic Republic’s own laws. It is also part of internationally recognized human rights included in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Iran is a party to,” the lawyer says.

He says that the Islamic Republic’s haste in carrying out executions leaves no opportunity for any appeal or pardon, even though the laws of the Islamic Republic do provide a mechanism for granting pardons and each province has a committee dedicated to this.

Rahnavard went on trial before Mashhad Revolutionary Court on November 28, less than 10 days after his arrest, and was executed on December 12, two days after his death sentence was issued. He had no chance whatsoever to appeal or to ask for pardon.

It appears that the gallows were ready for Rahnavard even before the verdict was issued and that the authorities quickly executed him to teach the Iranian protesters a lesson.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments