“Traces of cigarette burns can be clearly observed on the hands, the feet and the genitals of the eight-year-old girl. They were inflicted by her mother when she noticed the child was touching her genitals."

“The mother was a drug addict who was trying to quit and had no patience. On one occasion, she violently threw her child to the ground, causing the child’s face to swell up.”

These are just some of the stories that Children of Imprisoned Parents International (COIPI), a global NGO established in 2014, has compiled in the seven years since then about the treatment suffered by children on the women’s wards in Iranian prisons. In its most recent study, COIPI found that some children growing up behind bars at the notorious Qarchak Women’s Prison in Varamin were not only vulnerable to physical harm, but to deeply disturbing sexual abuse.

A former prisoner held at Qarchak in spring 2018 told COIPI: “They [the inmates] paid no attention to the little girls. But when it came to the little boys, they would get naked in front of them, they took them to the bathhouse with them, played with their genitals, attached clothespins or things like that to their genitals, and forced the children to touch their bodies. Women other than the mothers forced their breasts into the children’s mouths, taught the children sexual words and asked them to repeat them, or made sexually-charged phone calls in the presence of the children.”

The Far-Reaching Consequences of Abuse in Prison

According to Article 69 of the Iranian Prisons Organization’s regulations, female prison inmates can keep their children with them until the age of two. But in reality, they often stay with their mothers until they are much older.

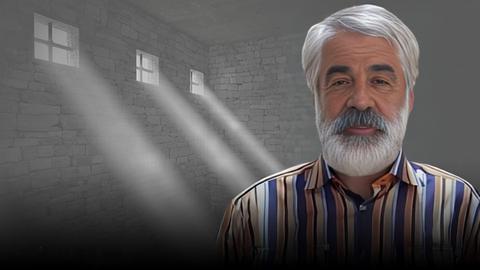

Hamed Farmand, the founder and president of COIPI, told IranWire that testimonies collected by the organization suggested these children regularly witness violence breaking out among inmates. They are also often exposed to drug abuse, and the torture and corporal punishment of inmates by prison guards. This, Farmand said, can lead them to suffer traumas that often stay with them well into adulthood, manifesting in anything from aggressive behavior to lethargy, nightmares to bedwetting, to shame and low self-esteem.

Of the latest report, Farmand said: “This study is based on interviews with women who were either released from prison in the last year or are still incarcerated, as well as with a number of specialists, including a social worker who works with the children of jailed mothers.” As well as past documentary evidence gathered by COIPI, the study features the direct testimonies of four ex-inmates, two given through intermediaries, and one from a current inmate. It spans incidents recorded at Sepidar Prison in Ahvaz, Bushehr Prison, Qarchak, Amol Prison in Mazandaran, Koochoie (Fardis) Prison in Karaj, Vakilabad Prison in Mashhad, Lakan Prison in Rasht, Bam Prison, Urmia Prison, and Adelabad Prison in Shiraz.

The study paid special attention to how the prison environment impacted children’s physical and psychological development. “We tried to study more than merely the secondary harms,” Farmand says. “True, prison children are unfamiliar with the trappings of everyday life: cars, open spaces, urban crowds, life in the city, playgrounds, parks, even the night sky, and since they are in the women’s prisons, they either haven’t seen men, or are afraid of them.

“But what we documented goes beyond this. The physical harms can take different forms. Prison children are punished by their mothers, even by other inmates, for different reasons such as the stressful environment, drug addiction or withdrawal, or a simply lack of awareness that physical punishment is wrong.” Simultaneously, the lack of security in some prisons can put children at risk. Many are denied access to adequate food, healthcare, clean water, clean air, and appropriate education for their age.

Products of a Misguided System

For Farmand, the conclusions to be drawn from the report are clear: “Prison is no place for children at all.” Some officials, he said, used the term “nurseries” when speaking to the media, but in reality “no such thing exists in Iranian prisons. Officials claim they have separate wards for mothers but we have material proof that not only are they not, but they have no access to additional facilities or services either. The lack of education, the density of the prison population, and the absence of a private space for these children and their mothers violate children’s rights.”

Women prisoners and their children, COIPI argues, should be completely separated from other inmates and offered a constellation of educational programs, as well as specialist nutrition and healthcare. But furthermore, Farmand says, “We insist that Iranian law be amended.

“Many of these mothers do not belong in prison. They are victims of poverty and the inefficiencies of the Iranian judicial system, in prison for ‘crimes’ that are not considered crimes by international convention. The jails would be less crowded if they were sentenced to alternate punishments and detained at home. They could bring up their children in a healthier environment, and these children are saved from the harms of prison.”

Related coverage:

Fact Check: Is the Iranian Judiciary Free to Execute Child Offenders?

The Lost Youth of Iran's Child Soldiers

Saving the Children of Prisoners from Victimhood

The Misfortune of Prison Children

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments