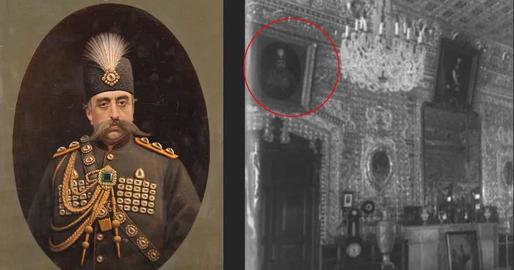

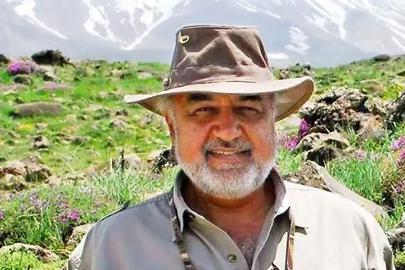

Earlier this month, Dr. Reza Kasravi, a painter and art historian, reported that a portrait of the Qajar king Mozaffar ad-Din Shah (d. 1907) by the renowned Iranian artist Kamal-ol-Molk was missing from Golestan Palace.

The palace is a former royal complex since converted into a museum, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In response to the claim, its director Afarin Emami said only that the painting was “not on the list of works owned” by the palace.

He has since learned the portrait changed hands at least as recently 2000. That year, it was auctioned off at Christie’s in London for £44,000, and today is in the collections of the Al Sabah family, the current rulers of Kuwait.

For its part, the Palace’s management holds that the item sold at Christie’s was a forgery: a claim that would be startling if true given the auction house’s repute. Kasravi insists that according to research he has conducted to date, there is no reason to suspect the portrait sold in London was not the original.

The apparent fate of Mozaffar ad-Din Shah’s portrait has captured the attention of observers in Iran. Official news outlets say no report of theft or loss has yet been filed with the authorities. But historian Hamid Reza Hosseini wrote: “All those who deny the theft will somehow benefit from doing so.

“If it is proven that this painting was lifted from Golestan Palace, the then-directors are without a doubt guilty of dereliction of duty. The current director might not have anything to do with it, but it is their duty to cooperate with the police and the judiciary, to provide them with the required documents, and to keep the media informed.”

A Shock Discovery

Reza Kasravi only noticed the portrait’s absence from its former place in the Palace’s Brilliant Hall at the close of a lengthy research project. Some time ago, he told IranWire, a friend had sent him a digitized copy of a picture hanging at the Institute for Iran Contemporary Historical Studies, which is now owned by the Mostazafan Foundation. It showed the interior of the Palace’s Brilliant Hall, so named because the walls are covered with mirrors.

“When I examined that picture carefully,” he said, “I noticed there were oil paintings hanging in the Brilliant Hall. One of them was that bust-length portrait of Mozaffar ad-Din Shah. In the middle, there was also a portrait of Ahmad Shah by Kamal-ol-Molk, which is now on display at the end of the Ivory Hall, and the third painting was a portrait of Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar.

“The paintings grabbed my attention because I’ve been working on a book about Kamal-ol-Molk with a friend for years. I’d read Kamal-ol-Molk’s memoirs 20 times or more, and could recall most of the details. I immediately looked again and, yes, Kamal-ol-Molk had painted just one portrait of Ahmad Shah, and just one bust-length portrait of Mozaffar ad-Din Shah.”

The picture of Ahmad Shah was dated 1913. Given the anti-Qajar atmosphere that prevailed during the reign of Reza Shah, the first Pahlavi king, Kasravi said he finds it hard to believe the black-and-white photo of the Brilliant Hall would have been taken during his reign. As such, he said, it was probably taken – and the pictures were then in situ – somewhere between 1913 and 1925.

The Auction in London

“Before I saw this picture, perhaps three years ago, another friend had given me a scanned catalogue of an April 2000 auction at Christie's in London,” Kasravi explained. “The [image] quality was superb. Of course, I’d already seen a picture of Mozaffar ad-Din Shah’s portrait on the web, but here you could see the masterly brushwork of the painter.

“The signature on the painting was also quite legible: ‘Your Servant, Kamal-ol-Molk, 1319 [Islamic Lunar Calendar, or 1902 CE]’, when Mozaffar ad-Din Shah was king. Everything matched the evidence we had. Naturally, the catalogue had also set a starting price.”

Kasravi had already spent years studying both authentic works by Kamal-ol-Molok and a great many fakes, using specialist computer software. Now, he set about trying to verify this painting’s authenticity.

“I held up the picture against all my knowledge of Kamal-ol-Molk’s life, his works, his style and brushwork in different periods. It has to be emphasized that I didn’t have access to the original and couldn’t test the painting professionally in a lab. But so far, at least, I haven’t found any evidence the painting wasn’t genuine.”

For around two years, Kasravi sat with the belief that a potentially priceless painting had left Iran and been sold. “I consulted with a few friends about breaking the story to the media,” he said. “Our hope is to see this painting returned to Iran. It’s great if museums around the world display works by Iranians, and very good for the promotion of Iranian arts and culture, but when a work is part of the royal collection, it’s different.”

Finally on July 15 this year, Kasravi published a detailed report on his findings to date, in a two-part post on Instagram. Since then, he said, “Some individuals have naturally given interviews that tried to cool things down. But nobody has been able to disprove my research.”

Was Mozaffar ad-Din Shah’s Portrait Stolen in 1979?

It is unclear exactly when the mortrait of Mozaffar ad-Din Shah would have left Iran. Kasravi notes that an auction took place in 1926, early on in the reign of Reza Shah, involving low-value antiques and items from Golestan Palace that were no longer needed. “But,” he said, “they would absolutely not have sold paintings by Kamal-ol-Molk. They also didn’t sell the portraits of any other Qajar kinds, so why would they have sold this one?”

There are other clues that suggest these paintings remained in Golestan Palace for decades after that. In 1957, a book by Yahya Zoka, a prominent art historian, describes a series of works by Kamal-ol-Molk depicting dethroned Qajar kings that had fallen into poor condition. Years later, another report by the Iran National Archive said the great painter and Kamal-ol-Molk acolyte Hossein Sheik, also known as Hossein Ehia, had been invited to Golestan Palace to restore the portraits by his former master.

There is, Kasravi says, a chance the painting was removed during the tumult of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. “It’s quite possible that paintings and artefacts were taken outside the country in the confusion of those days. But as of now, nobody has come forward with any evidence as to when the painting left the palace.”

Well-informed contacts allowed Kasravi to establish the current ownership of the Mozaffar ad-Din portrait to Kuwait. Despite remarks made to the media, the management of Golestan Palace is now working on a case file to send to the Ministry of Cultural Heritage. If necessary, the Ministry can then contact Interpol as Iran is a member of the UNESCO Convention on Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.

“The responsible institutions may not want to be transparent about it,” Kasravi said. “Or they might give us inaccurate information. I’d intended to put together a full report and give it to the directors of Golestan Palace [first], but in the end I decided to publish my incomplete research so others would know about it. Our national heritage must be returned to us.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments

Would not Dr. Layla Diba be the obvious person to sort this out?

She is the world’s expert in this field of art and was the curator of the palace during the King’s reign in the 1970’s.