It would be difficult to find an Iranian artist or a writer who has no memories of censorship over the past three decades. How can you publish a book or stage a play without being stressed by the threat of the censor’s scalpel? When I lived in Iran and sent a book to the publisher for a license or my page to the editor-in-chief for approval, I always asked myself this question: Do journalists, writers and poets close to the establishment of the Islamic Republic, people like Hossein Shariatmadari, the managing editor of the hardliner daily Keyhan, have any idea of what censorship is actually about? When I was most troubled I often thought about how for these people censorship was entirely intangible, and this thought brought a smile to my face.

A few months ago I prepared a special for IranWire on book censorship in Iran. It covered on various aspects of censorship but the stories below show a more hidden and ironic side that has rarely been reported.

Censorship In All But Name

By Mojtaba Youssef-Pour

My most ridiculous censorship story is about staging a play and the obstacle course that one must negotiate to get a pile of permits. If you overcome the first obstacle and your text is approved, you must still secure approval for the theater company as a whole and for each member. When you pass this obstacle, it is time to get a permit for performance. When all obstacles are conquered then you should keep your fingers crossed because a governmental organization or the Basij or the local mosque might object and whole performance will be canceled.

After rehearsing the play “Arash” we performed it at the Theater Festival, hoping that afterwards we would be able to stage it in the city, using the festival permits. No one spoke of censorship or banning the performance, but no theater wanted to perform the play. After a few months of running from one theater director to another we gave up and the case was closed without a public performance.

The play “Babak” was a different adventure, however. First we were unable to get a permit for the script, so we appealed to the theater festival again and their reviewers secured us a permit. We rehearsed the play, but after our first and last performance, they shut it down for “review” and threw out our stage props. We lost months of work that simply.

What deserves more reflection than anything else, however, is that the censors replace the negative word “censorship” with terms such as “auditing” and “revision” to justify their distasteful job. Unfortunately many Iranian artists cooperate with censorship by using the same dishonest words. The most ridiculous kind of censorship is in fact censoring the word “censorship”. This censorship deserves a strong “No!”.

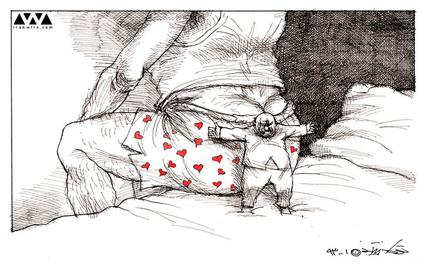

Seat, Not Buttocks

By Ehsan A., Novelist

I have lost my patience, so screw them. Before talking about my experience with ridiculous censorship, allow me to write this sentence so that I would know that it has been published somewhere and has not been censored. No, not once. I want to write it a few times: “The man sat on the edge of the bed and turned around on his buttocks. The man sat on the edge of the bed and turned around on his buttocks.” Take that, Mr. or Ms. Censor who censored my book! I succeeded and published the sentence.

Believe me, censorship is not funny at all; it hurts more than it amuses. I recently sent a book to a publisher and the “auditors” of the Ministry of Islamic Guidance changed the story for me. Sorry, no, I should say they destroyed the story. For example they wrote that “cabaret” must be changed to “Café”, and Googoosh, the contemporary Iranian singer must be replaced by Qamar who died in 1959. This was just a single sentence. Now what do you think: laugh at censorship or explode in anger?

Mademoiselle’s Scarf

Hooman Azizi

More than ten years ago we staged the “The Government Inspector” by Nikolai Gogol in the western city of Kermanshah. It was directed by Abbas Bani Amerian and it was the first of its, because never before had the city seen a play with such a large cast of characters.

The play has about 33 characters and lasts more than three hours. For this reason—and of course because of the director’s perfectionism—the preparations and the rehearsal had taken a year.

The play, which can be called a prelude to realism in theater, is a comedy about the innate corruption of the Tsarist Russia, but its observations can extend to all totalitarian systems as a critique of the ruling power. For this very reason it was not a play that the Islamic Republic and the Ministry of Islamic Guidance were keen on staging. Fortunately the officials at the ministry’s local office were not sophisticated enough to understand this and did not throw obstacles in our way. When the performances started it was too late because any interference would have provoked the public to talk and speculate about it and they did not want that, especially in a town where people were not very familiar with theater and the play would not draw a large audience in any case.

But “The Government Inspector” attracted attention and after the first few performances the office of Islamic Guidance started to censor the play, even though it had issued a permit before it opened. Interestingly enough, the agents of censorship were not bright enough to be effective and the process of censorship took a humorous turn.

In one scene, Khlestakov, the main character (played by me) who has been mistaken for the inspector is left alone with Marya Antonovna, the daughter of the governor whom he intends to shake down. He begins by wooing the governor’s daughter:

Khlestakov: What a beautiful scarf you have!

Marya: You are making fun of me—you're only laughing at countrified people!

Khlestakov: How I should long, mademoiselle, to be that scarf, so as to clasp your lily neck!

This was one scene of dialogue that we were told to remove. But we performed it every night because after more than a year of rehearsals we could not forget what we had memorized by obeying a simple directive. The words came out unintentionally.

The funny part was that the ignorant censors missed all the scenes about political and financial corruptions that could have been interpreted as a critique of the government, but dialogue like “How I should long to be that scarf” became the main problem with the play.

Funnier still was that after each performance the censorship agents came backstage and angrily showed us the list of dialogue and gestures that were supposed to have been taken out but had not been. I explained to them that the long rehearsal made me to speak the words unintentionally and I forgot that I should not say them. Still funnier was that every time they would accept my excuse. The day after, however, they came back with a longer list and same thing happened over and over until the end.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments