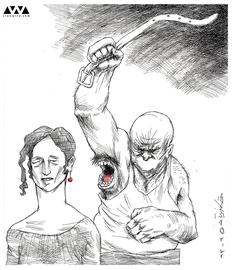

Until she was blindfolded and forced to sit facing the wall of the interrogation room, Fereshteh Ghazi never imagined she could be threatened with rape; she never expected her interrogators to demand she confess to having illicit sexual relations with people she had never met.

Hundreds of journalists and political activists have been arrested in Iran, many of whom are subjected to torture, to confess crimes they never committed and kept in inhumane conditions, often in solitary confinement. These men and women are accused of immorality, of being the "enemies of god" and of spying for "hostile" Western governments. Journalist and human rights activist Fereshteh Ghazi was one of the first women to talk publicly about her ordeal, giving courage to other female reporters subjected to similar treatment to tell their stories.

Saeed Mortazavi, then Prosecutor General of Tehran, ordered the arrest of Ghazi and several other journalists on October 28, 2004. He was later suspended in 2010 after three anti-government protesters died in custody at Kahrizak Prison in 2009. Finally, on October 15, 2014, he was disbarred.

Ghazi's arrest and that of her colleagues, known in Iran as the “Websites Case,” it attracted considerable international media attention. Following their release, the journalists refused to be silent, speaking out about what happened to them and the brutal treatment they endured in prison, which included everything from rape threats to other forms of mental torture. The journalists told their experiences to the Board of Constitutional Supervision and to the former Judiciary Chief Ayatollah Hashemi Shahroudi.

IranWire spoke to Ghazi about the charges against her and her interrogator’s repeated threats against her.

Prior to your arrest, did you have any idea that you might face accusations of illicit relationships or face charges of immorality?

No, it was different then [in 2004]. Today, they regularly threaten rape or accuse people of non-existent illicit relationships and immoral acts; it is used as a tool by the interrogator to torture the detainee. At that time, we did hear indirectly that an arrested journalist or political activist had been accused of things like illicit relationships or drinking alcohol or using drugs, but since they themselves never talked about it, it remained at the level of rumors for us. I myself never imagined that if I were arrested such a thing would happen to me.

What was your reaction when it happened to you?

I was shocked. I was dizzy for a time and could not really believe what I was hearing. I went on hunger strike but it was useless. Nothing changed. Judge Zafar Ghandi said, “I’ll show you what we do with professional prisoners!” They believed hunger strikes were for professional prisoners.

How did the interrogator behave when he made such accusations?

More than anything else I think that my interrogator was sex-obsessed and enjoyed making these accusations during interrogations. I heard this from my co-defendants, who were interrogated by the same person. His tone, the way he talked and the words he used — none of these were the words or actions of a normal person.

Can you tell us what he said to you?

He wanted me to confess to illicit relationships with people in important positions at the time, from Mostafa Tajzadeh [the political vice minister of the Ministry of Interior], Ata’ollah Mohajerani and Mohammad-Ali Abtahi [both former vice presidents for legal and parliamentary affairs] up to [then President] Khatami himself. I had never met some of the people whose names were brought up, or had met them only briefly. But the interrogator wanted me to confess to illicit relationships with them. When I did not reply, the interrogator himself started talking in a disgusting and irritating way. He told stories about illicit relationships as if he was describing a porn flick.

Were you forced to confess?

They accused me of two things and applied pressure on me to accept at least one of them. I either had to accept illicit relationships or to confess that I was a spy. I confessed to spying because it involved only myself. Had I confessed to illicit relationships, other people would have been implicated.

Did you see your interrogator’s face?

At the beginning, when I was kept at the “secret detention center,” I was always interrogated while blindfolded. But once, when he made accusations of immorality, I stood up, as a way to protest, and removed my blindfold. The interrogator kicked the chair from behind, my face hit the chair’s arm and I broke my nose. When I was transferred to Evin Prison, the interrogations stopped. The interrogator just wanted me to confess in front of the camera. I was not blindfolded during these sessions. After I was released, I became aware that the same man had also interrogated my co-defendants under two different names, Keshavarz and Fallah. A year and a half after the arrest I traveled outside the country and when I returned, I was summoned by the Intelligence Ministry. There he was, the same interrogator.

Was Mortazavi present at any of your interrogations?

I recognized his voice once in the detention center. As a reporter, I had attended press conferences many times. Before my arrest, he had interrogated me once. I was familiar with his voice and his expressions. After the arrest he interrogated us many times in his own office.

As the prosecutor, did he ever make his own accusations of immorality?

Saeed Mortazavi tried not say such things publicly. But once, when he expelled my lawyer from the room, he came very close to me so that I could feel his breath on my face. He told me that whatever the interrogator said could happen. The interrogator had threatened me with rape repeatedly. “There are many men here who have not seen a woman for years,” he would say. “We will put you in the same cell with them.” Or he would say: “accidents happen a lot in Iran. Maybe your husband will be run over by a car”. And so on. I was shocked when Mortazavi said that such things could happen. I wanted to complain against the interrogator but the prosecutor was affirming what the interrogator had said. They were in cahoots.

Did you talk about this treatment after you were released?

I had been hurt a lot, so I talked about it publicly. I thought if those who had been arrested before me had talked about it at least I could have been spared the shock and could have been a little better prepared for the interrogations. I remember that the atmosphere was so suffocating that when I talked to my colleagues about this inhuman behavior and the charges of immorality some would say ,“don’t talk about it. It will cost you.” I asked: why shouldn’t I? When I was released I talked, more than anything else, about applying pressure through false immorality charges. I wanted those who might be arrested after me to at least know what to expect and what the interrogations were about. I brought up the subject in meetings with any official that I could get to.

I was under the impression that if the subject was brought up it could be prevented. I was wrong of course. The process continued after us and is still continuing.

Did you mention the accusations of immorality and the way interrogations were conducted in your meeting with Ayatollah Hashemi Shahroudi?

When we met Mr. Shahroudi he told us not to talk about the immorality accusations, which were brought up in the interrogations, and just stick with the political charges. I said that they were my main complaint. As a journalist, I must know why I have been accused of illicit relationships and why I could not talk about it. I recounted all the details. I felt so bad that I left the meeting in the middle of it. Later on Mr. Khatami quoted Mr. Shahroudi as saying that “she felt so bad that it touched me.”

Who told you not to talk about these issues?

By some of the people who had helped to set up the meeting. Mr. Shahroudi’s assistant. Even some of my co-defendants, who were reluctant to talk about it because of the atmosphere that existed. Of course [later] they described it in detail.

What was Shahroudi’s reaction when he heard these things?

The first thing Shahroudi said was very interesting. “Mr. Mortazavi told me that you have done vulgar things on the internet,” he said. “You have published vulgar pictures of the Shia imams, Imam Khomeini, the Leader [Khamenei] and even Mr. Khatami.”

“Computers are bad,” he advised us. “I have a computer at home but when I leave home I lock the door to the room so that my daughter will not touch it and will not be infected with vice.”

Mr. Shahroudi really believed that we created those pictures — for example, one of Ayatollah Khamenei in his underwear — and posted them online. Think about it. The Judiciary Chief did not know the facts about a case that was talked about around the world. Kofi Annan, the UN Secretary General at the time, had spoken about it.

When we started to talk it was clear that he was shocked. We had been given half an hour to talk and then he had to go to a meeting, to a session of the Supreme Council on Cultural Revolution if I am not mistaken. But the meeting continued on as we talked. Mr. Shahroudi did not go to the meeting and continued to listen to us carefully.

Did the meeting produce any results?

After meeting with Mr. Shahroudi we were no longer summoned by Mortazavi and the case was taken away from him. Between the time when we were released and our meeting with Shahroudi, I had been summoned and interrogated 13 times by Mortazavi.

After this meeting you attended a meeting of the Board of Constitutional Supervision and told them about the interrogations. What was their reaction?

We met the Board of Constitutional Supervision before we met Mr. Shahroudi. Mr. Khatami had placed the board in charge of reviewing our case. We explained the issues to the board in detail, from immorality and security accusations and charges of spying to their unlawful behavior, from illegal arrests to the secret detention center and all that had happened in detention and later at Evin Prison. They were deeply affected.

But I still remember one thing from the meeting that makes me smile bitterly when I think about it. Imagine, we had explained everything: threats of rape and threats to arrest or to kill family members, accusations of immoral behavior and spying, beatings and my broken nose. Then suddenly Hashemzadeh Harisi, who is also a member of the Assembly of Experts, interjected and said, “Mrs. Ghazi, I have only one question: Was your interrogator a man or a woman?”

These days, many people talk about similar experiences. When you hear it from people who have been arrested recently, how much are you reminded of your own experience?

To tell you the truth, I feel very bitter and hurt. I experienced it with my flesh and with every bone in my body. I am sad that all the efforts my colleagues and I made to speak out, so that the authorities would prevent the process from being repeated, have not led to any results. Despite all the pressures and risks, we did not stay silent. We gave interviews and went to the authorities. Some doubted us, and did not like what we were saying. They asked us to keep silent and only talk about political and security interrogations. We did not heed their advice and continued talking.

Unfortunately we were wrong, and the process has continued.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments