Beheadings and burning people alive are no longer enough for Islamic State and its thirst for savagery. On March 6, there was widespread condemnation for the militant group’s destruction of the ancient Assyrian site of Nimrud in Iraq. And, in late February, media around the world published footage of the extremist group destroying statues and other artifacts at Mosul museum. The bulldozing and leveling is part of Islamic State's far-reaching goal to rid the region of “false idols” and anti-Islamic icons.

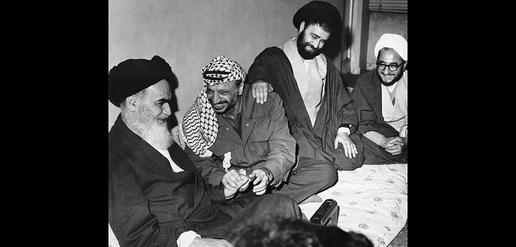

For many Iranians, the destruction of historical monuments is synonymous with Sadegh Khalkhali. Known as one of the country’s most brutal “hanging judges,” it is believed that he sent around 8,000 people to their deaths long before his own death of natural causes in 2003. It is not a legacy Iranians will soon forget.

But Khalkhali is also remembered for his destruction of a large number of artefacts and monuments from Iran’s long history. He was so notorious that when, in 2001, the Taliban destroyed ancient statues of the Buddha in the Bamian province of Afghanistan, a number of commentators quipped: “Sleep easy, Khalkhali, for the Taliban are awake.”

Revolutionary Rewrites

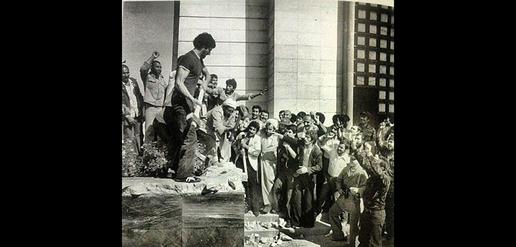

“From the moment the Shah escaped Iran, people started tearing down statues of Mohammad Reza and [his father] Reza,” wrote Khalkhali in his 1999 memoirs. “By 10pm, not one of those statues was left standing in Iran. People had crushed them all.”

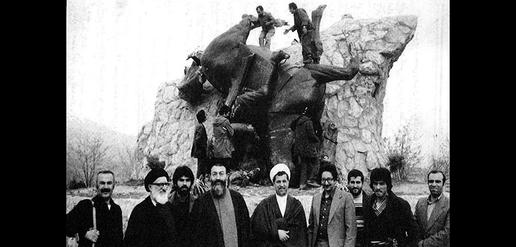

In a powerful expression of the revolutionaries’ hatred of the Pahlavi regime, Khalkhali led the campaign to destroy all statues of Reza Shah in the country. “It was time to destroy the Pahlavi Tomb,” Khalkhali wrote. He described how about 200 people, including members of the Revolutionary Guards, set off. Seyyad Abolhassan Banisadr, the first president of the Islamic Republic, appealed to the group, and instructed them not to destroy the tomb. But, wrote Khalkhali, “I paid it no attention.”

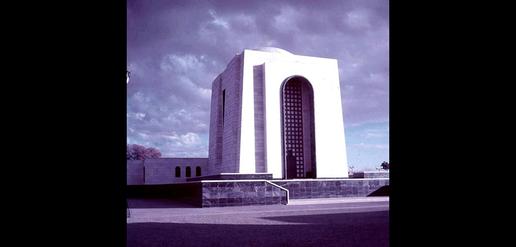

“Perhaps you do not know how sturdy this tomb was. We were chipping away at it... Bulldozers, graders and other equipment were ineffective. We were forced to destroy the tomb little by little with dynamite. It took 20 days for that Satanic edifice to come down. Imam [Ayatollah Khomeini] stated his approval... We destroyed the graves of Alireza Pahlavi [the Shah’s brother], Fazlollah Zahedi and Mansour [the Shah’s prime ministers] and other leaders of the corruption. We ordered the destruction of the tombstone of Nasseredin Shah [the 19th-century Iranian king].”

Khalkhali, however, had even more ambitious goals. Shortly after the revolution, he set out to topple Cyrus the Great too — and this time it was not a matter of destroying statues, it was about dismantling narratives, some of which formed the backbone of Iranian heritage and identity. According to Khalkhali, praise for Cyrus throughout history was no more than a series of fabrications by the Shah; he dismissed the many Koranic commentators who equated Cyrus with the revered ruler Dhul-Qarnayn. In a pamphlet entitled “Cyrus the Imposter,” Khalkhali presented Cyrus as brutal, bloodthirsty, debauched, tyrannical, Jewish and a homosexual.

At the time, it was unclear where Khalkhali got the idea that Cyrus was a homosexual, but it was later discovered that he had misread a phrase in a well-known Persian-language history book, which quotes a legend. The legend says Cyrus was of noble birth but was brought up by a shepherd and chose banditry out of desperation. Since in Persian writing diacritical marks for vowels are often left out, Khalkhali had read the term “bandit” (rah-zan) as “the way of women” (rah-e zan), which he decided meant a homosexual. The source of another claim, that Cyrus massacred anti-Semites, remains a mystery, though it is possible that he had subscribed to a warped version of the Biblical story of Esther and Mordecai.

The famous Cyrus Cylinder, now in the British Museum, held no value for Khalkhali as a symbol of human rights or as a historical artifact. The clay object, which dates back to 539-530 BC, gives an account of Cyrus’ conquest of the last Babylonian king and the liberation of oppressed people in Babylon.

After finishing the destruction in Tehran, Khalkhali set out to destroy Persepolis, the most magnificent reminder of the Persian Empire. “Khalkhali declared that his bunch of thugs were coming to destroy Persepolis,” wrote Nosratollah Amini, governor of the Fars province at the time. “I went on the radio and declared that such a treachery could only happen over my dead body. I ordered the military to be prepared to confront them upon their arrival in Shiraz. But before they could carry out their dirty mission, they were ordered back.”

In fact, Persepolis just escaped destruction. In 2000, in an interview with the New York Times, Shiraz’s Ayatollah Majdeddin Mahallati described how Khalkhali and his “band of thugs” arrived in Persepolis. “After a thundering speech linking Cyrus to the late Shah,[he] tried to destroy Persepolis. Mercifully, he and his rabble were stopped by local residents and the clergy.” A former judicial official supported this version of events. In an anonymous account, he said Khalkhali retreated after hearing about the objections of the local people and religious leaders.

Persepolis was not the only site under threat. There were attempts to destroy the tomb of Ferdowsi, Iran’s national poet, who some hardliner clerics detest. In Shiraz, vandals damaged statues and historical artefacts. In the ancient city of Isfahan, mobs attacked the home of prominent Iranian sculptor Ali Akbar Sanati and destroyed many of his works. In Tehran, people pulled down statuettes of lions over the entrance of the old parliament building. The “Lion-and-Sun” is an ancient pictorial motif throughout Iranian history but, again, this was interpreted as a symbol of the hated monarchy. In 2008, the Islamic parliament returned the lions to their original location — without the sun.

A Tradition of Destruction Lives on

Evidently, the urge to destroy history did not end with Khalkhali. In recent years, hardliner clergy have shown their distaste for historical artifacts, as well as modern depictions of Iranian history and mythology. In 2001, Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati, chairman of the influential Guardian Council, vehemently opposed a statue of the mythological figure Kaveh the Blacksmith, a symbol of the people’s will, in Isfahan. In 2010, thieves removed 12 statues in Tehran. And, in February 2015, the Islamic Council of the northwestern city of Salmas removed a statue of Ferdowsi from a town square, leading to a storm of protests. Opposition to the statue’s removal was so widespread that, eventually, the mayor gave in and promised to return the statue to its original place.

In October 1995, in a rare statement on the subject, the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, agreed with Khalkhali: the ruins of Persepolis, he said, are “examples of fallacy,” a gross misrepresentation of Iranian history, a belief he reiterated in April 2008 when he said, “hatred of tyranny and despotism removes any charm that they might have.”

Yet the Supreme Leader has not been consistent on Persepolis, and has also referred to the World Heritage site as “a product of the artistic, creative, lofty and innovative” Iranian mind. “It is a source of pride for the Iranian nation.”

Comments like this go some way to reduce the risk that historical sites like Persepolis will be destroyed, but they do little to combat hostility toward the perceived message these historical icons send — particularly when they are seen to undermine Islamic values. In March 1999, Khamenei criticized people who hoped to celebrate the new Iranian calendar year in Persepolis, urging them to revere holy places instead. “There is no spirituality there,” he said. “It is a symbol of godlessness.” He also reminded the public that innocent people had died in the buildings that once stood on the site, all in the name of celebrating a meaningless holiday.

Whether it is the Supreme Leader or ordinary people, the specter of Sadegh Khalkhali haunts Iran, commanding influence over how it views its history and identity, and leaving a legacy of destruction as an effective means of securing power.

So if Khalkhali was alive, how would he react to Islamic State’s destruction of historical artifacts in Iraq? Just before his death, he was asked if he felt remorse for the executions he had ordered after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. His answer: “I believe I did not kill enough. There were many who escaped my grasp.” It follows that his campaign to destroy history was also something he viewed as incomplete. Given the chance, he would have gone further. Watching as Islamic State destroys ancient antiquities in Iraq, many Iranians may well be pleased Khalkhali did not finish the job.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments