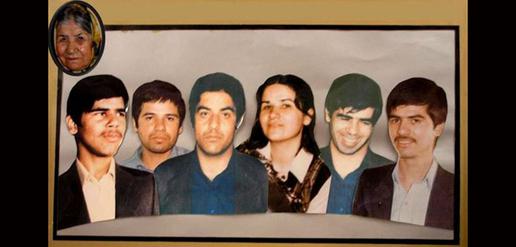

Every day a woman used to come to the cemetery holding a picture. It was a photograph of six smiling faces, among them a young woman with shiny black hair, which she held close to her chest, facing outward so everybody at the ceremony would have a clear view of it.

Nayereh Jalali, also known as Mother Behkish, was a member of the Mothers of Khavaran, a grassroots group of grieving mothers whose sons and daughters were killed in street shoot-outs or who perished in mass executions in the 1980s. The mothers search for any sign of their loved one — an unmarked grave, a bone, anything. The group took their name from Khavaran Cemetery in southeastern Tehran, which was used by the Islamic Republic to bury the “doomed”— communists, leftists, members of the People’s Mojahedin Organization and the Baha’is.

Mother Behkish, who lost four sons, a daughter and a son-in-law in the 1980s, died on Sunday, January 3 in her home in Tehran.

“She could have left Iran but she stayed in Tehran,” Parvaneh, who lost her brother in the mass executions of 1988, told IranWire. “She remained a devoted Muslim until she died, even though her children lost their lives following very different ideologies. She never tried to force her children to give up their chosen paths and always respected their beliefs.”

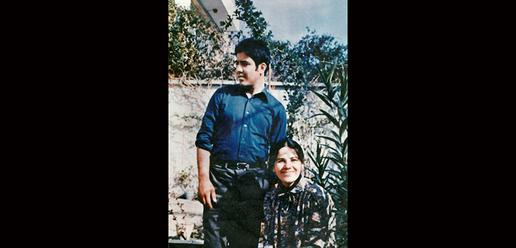

A friend sent me photographs from the home of Mother Behkish. The walls of her home are covered with old pictures: Her daughter Zahra, who had a master’s degree in physics; her son Mohammad, whom some say was not armed, who was gunned down in a house the government believed to be the headquarters of opposition political activism; the smiling face of a young Mohsen in the giddy days after Ayatollah Khomeini came to power and who was executed five years after the revolution; Mahmood, who was sentenced to life imprisonment under the Shah, and who served a five-year prison sentence under the Islamic Republic and then executed instead of released when he should have been; Ali, who was only 19, and who was arrested for distributing leaflets and executed although he had not been sentenced to death — authorities presented his mother with his meager belongings after he died; her son-in-law Siamak, who was killed in armed clashes of 1981.

Looking for Graves and for Justice

“There was something about that cemetery that made me travel there from Isfahan every two weeks, even though we did not know whether our loved ones were buried there or not,” said Ms. Saberi, another member of the Mothers of Khavaran who lost her young husband. “Only a few graves were marked. The rest were anonymous. Every time I went there, Mother Behkish was there too, with her famous group portrait of her children. She said that she had searched day after day and grave after grave to find a sign of her children. She did not know whether all her children were buried there or not. She said: ‘after all the comings and goings they only showed me the grave of one of my children.’ She was not in the habit of crying and weeping. She must have cried when she was alone, like all of us who have never forgotten about our loved ones. We saw a woman who had accepted her children as they were and wanted to understand why they had died. She wanted to know how it had happened, and she was asking for justice.”

“Until my last day in Iran, every two weeks I visited Khavaran and she was always there,” Saberi said. “We went around and put flowers on the arid ground. We stood together, recited poetry, talked and comforted each other. The graves of a few people, like those of Saeed Azarang or Kiumars Zarshenas, were marked. But the rest have probably been buried in mass graves. Mother Behkish said that at first she searched Behesht Zahra [Tehran’s main cemetery]. A cemetery employee who had witnessed her comings and goings took pity on her and gave her the address of Khavaran, telling her that was the place where they buried the people who died for political reasons.”

“Grieving for one’s child is too hard,” Mother Behkish told the Iran Tribunal Organization before her death. “Not only one or two, but five — which becomes six if you add my son-in-law. And they were excellent kids, one lovelier than the next. I pray in their names and I hope that one day I will get justice. It took them three months after they killed Mahmood and Ali to give us their bags. They did not even give us their wills and said that they had torn them up. No matter how much I cried and begged them to tell us where they were buried, they refused. For long periods of time, I wandered between Evin Prison and Behesht Zahra Cemetery. At the cemetery they told us that we must ask at Evin. At Evin they would tell us to ask at Behesht Zahra. At last an employee of Behesht Zahra took pity on us and gave us the address of Khavaran.

“My husband and I went to Khavaran and saw the extent of the tragedy. In the last three years of his life, my husband went mad. He loved the kids, especially Zahra and Mahmood. He would sit on a carpet at the doorway of our house and would say: ‘I am on the lookout so that they will not come and hang us in the street.’ When I asked him, ‘What have we done so that they would hang us?,’ he would answer, ‘Nothing. But what did our children do?’”

Challenging the Policy of Oblivion

Maryam also lost her husband to Khavaran Cemetery. She herself spent four years in prison. “The importance of Ms. Jalali was not only her remarkable endurance, but she also had an important role in the campaign to shed light on the deaths of those buried in Khavaran,” she said. “In those early years she was an active member of the campaign to seek justice. They were the watchful part of the conscience of society. They had been forced to forget and stay silent through enormous pressures. It was important to keep the memories of those years alive. The peaceful struggle of our mothers became a social movement. They did something important. They challenged the policy of forgetfulness.”

“Even though she was a devout Muslim, Mother Behkish did not impose it on her children,” says Maryam. “Her children were free to choose their own path and she supported them. This was remarkable. She recognized both her own rights and the rights of the others. She believed that it was part of the duty of being a mother. She treated them with respect and in turn, she permitted others to challenge her religious beliefs.”

“Mother Behkish and the other Mothers of Khavaran came to know each other outside the prisons, where they stood and asked for justice,” Monireh Baradaran, a human rights activist who has spent nine years of her life in Iranian prisons, told IranWire. “In the summer of 1988 when authorities banned visits to inmates, something ominous happened. The mothers shared their loneliness. They gathered together, searched cemeteries and learned that their beloved had been buried in mass graves in Khavaran Cemetery. Khavaran became their meeting place. They did not keep the pain and grief of losing their loved ones private. Instead, they transformed it into a social and political campaign for discovering the truth and to demand accountability.”

On November 11, 2011 Mother Behkish contacted the United Nations, challenging UN officials about their silence in the face of executions. “Why have you never talked about my children? What sins did these children commit? Why did they kill them? How much injustice is enough? What is the UN for? To praise themselves? What about our children and our nation?”

The Mothers of Khavaran do not have a formal structure or a charter. They have faced constant harassment from the regime. But slowly, they have found international recognition. The group was awarded the 2014 Gwangju Prize for Human Rights, which the South Korean May 18 Memorial Foundation presents annually to “individuals, groups or institutions in Korea and abroad that have contributed to promoting and advancing human rights, democracy and peace through their work.”

Mansoureh Behkish, Mother Behkish’s daughter, told the International Campaign for human Rights in Iran about her most recent appeal on behalf of the group: “I even wrote a letter of protest to President Rouhani and asked him 12 questions laying out the minimum demands of the families. I asked him to unlock the gate to Khavaran Cemetery and to end the harassment and abuse of the families. But nothing has changed. None of the authorities in charge have even responded.”

Mother Behkish’s work will continue, and her vision will live on through the Mothers of Khavaran.

Related articles:

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments