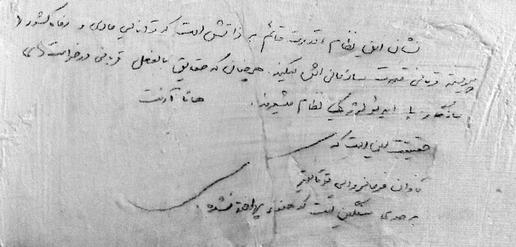

Mohsen had promised to send IranWire his pictures of prison graffiti, but the graffiti in his photos is difficult to read. When I point this out he laughs and says, “I must do something so that they will send me to solitary. What people write on the walls there is breathtaking. In solitary confinement, Graffiti is what nourishes you.”

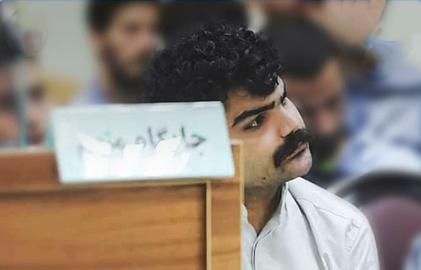

“When I was in solitary confinement,” he says, “I lived with the graffiti on the walls of my cell. The thoughts of any prisoner in isolation get reflected on the walls of his cell, whether he wants them to or not. By writing on the wall, the prisoner says to himself, and to life itself, that he still exists. By repeating his thoughts and his beliefs, and by recording what is consuming him in those moments, he is talking to future occupants of the cell.”

“The graffiti are the cries of the prisoners,” says one of Mohsen’s ward-mates, who has also experienced solitary confinement. “This is the only place in the prison where the prisoner can say what he wants without censorship and without pressure.”

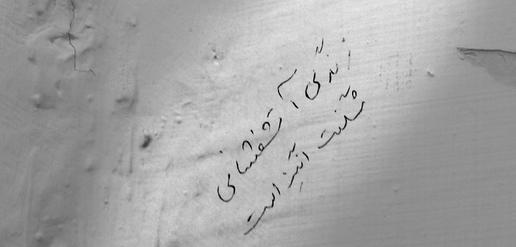

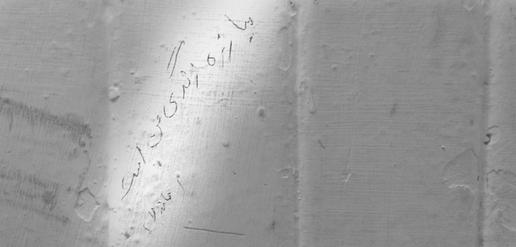

Alireza, another Evin inmate who has spent six months in solitary confinement at the Revolutionary Guards-controlled Ward 2A, has his own take on the graffiti. “I wrote a lot on the walls,” he says. “If I hadn’t, I would have gone mad. I searched the walls for one word or one scratch left by the previous occupant. I believe these are the words the prisoner did not tell the interrogator. That is why the interrogators keep track of the graffiti. When the inmate is out of the cell, they come in and scan the walls in search of facts he has hidden. Graffiti is one of the tools the interrogators use to prove to the prisoner that he is lying.”

Alireza says that before he was transferred to a new cell, the guards had cleaned the walls. “It disappointed me,” he says. “This is what the guards have been doing recently. They have wised up. Before transferring the inmate into a new cell, they clean the walls with water, towels and chemicals. On Evin’s 2A and 209 wards the walls are the only areas where the cleanup is not assigned to prisoners. They don’t want the prisoners to exchange messages or get a morale boost by seeing graffiti.”

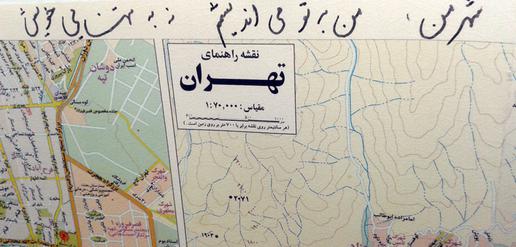

“The same walls that separate the prisoner from life sometimes turn into the only connection between him and life,” says Alireza. “The walls—whether they are made up of bricks, marble, plasterboards or metal—are the prisoner’s companions. The walls talk. They are our attendance sheet and roll call. Through them we learn who before us has breathed in that confined space, who has suffered, and who has stood by his beliefs. They are also our calendars, and they remind us of the time that has passed.”

“Reading and writing graffiti is the solitary prisoner’s sustenance,” writes Peyman Roshanzamir, blogger and editor-in-chief of the news site Haft-e Tir, in his prison memoirs.

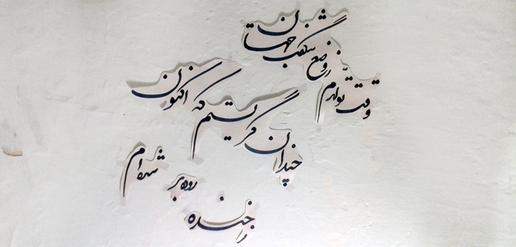

“My walls were covered with poetry. They told me to close the door and then take off my blindfold. An empty plastic jug and a worn-out carpet were the only contents of the two-by-three meter cell. After two minutes the guy who had put me in the cell came back with three blankets, a toothbrush and a tube of toothpaste. He said that if I wanted something I should ring the bell, but I must never knock on the door. I asked how I could write on the wall. ‘You are not going to write on the wall,’ he said.”

“The best pastime in solitary is going over the graffiti which has been left behind,” writes Roshanzamir. “In cell 13, where I was kept, all the graffiti was in Arabic except a few sentences by [the student activist] Javad Alikhani from years earlier. This redoubled my determination to write on the wall the moment that I entered the cell.

“‘I cannot read what others before me have written,’ I said to myself. ‘The least I can do is to cover the walls with Persian for the next person who does not speak Arabic. Then he would have something with which to kill time.’ And soon enough I found something to write with: A two millimeter-long piece of metal that had been left in a corner of the cell by a previous occupant. And another occupant had given the location of another tool that he had hidden in a crack in the wall. ‘Find it and write with it,’ it said. On the third day of my detention I found it. It was a piece of aluminum. When you drew with it on the wall it left its trace like a pencil. Thank god that because of these tools, I did not have to steal a pen during interrogations.”

“A friend said to me that the walls of these cells belong to the public and they must not be damaged,” says Mohsen. “I find it interesting. He meant that these walls, built to imprison him and to squeeze the life out of him, belong to the people and to the future, and that one day, they will become part of a museum. Even a wall that the guards censor with bleach and chemicals will still keep its memories and its history. You cannot wipe out the memories of life and death from those walls, no matter what chemicals you use.”

Related Articles:

Tehran's Walls: A New Canvas for Protest

Black Hand, Iran's Underground Banksy

"Fuck U, Villain": Iran's Ashoura Graffiti

Read more from Fereshteh Nasehi'sseries

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

![“We will [overcome]” “We will [overcome]”](https://static.prod.iranwire.com/_versions_jpg/filer_public/04/90/04900952-9e35-40b3-8ff0-09328d03b123/no_title__v516x270__.jpg)

comments