As a near-absolute ruler of a major country, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei is not used to hearing the word "no". So one can only imagine his outrage when an American tech company, Twitter, told him that he’d have to delete a tweet he posted from his official account or else the whole account would be taken down. He seems to have quietly complied, according to analysts of the Iranian internet.

The tweet in question simply reiterated a world-famous order by Khamenei’s predecessor, Ayatollah Khomeini, on its 30th anniversary. Khomeini had picked Valentine’s Day, 1989, to call for Muslims the world over to take any action they could to murder Salman Rushdie, a British Muslim writer whose book The Satanic Verses wasn’t to Khomeini’s liking. Thirty years later, Khamenei marked Valentine’s Day with the following tweet: “Imam Khomeini’s verdict regarding Salman Rushdie is based on divine verses and just like divine verses, it is solid and irrevocable.”

The tweet goes against Twitter’s policy against death threats, as the company told the Washington Post. It has now been taken down.

For a man who denies the Holocaust and sits atop one of the most brutal regimes of oppression in the world, the open order for the assassination of a writer might not seem that outlandish. Many will even regard it as a familiar refrain. But less well known is a detail about Khamenei that serves to thicken the plot. Like a good number of authoritarian leaders, he fancies himself a man of letters and an expert opinion on literature.

It was just a few months ago that Khamenei sent a poem to a national congress that was tasked with commemorating poetry dedicated to the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988. Khamenei’s six-verse ghazal is written in a late-medieval style and doesn’t appear to be anything special. He has written sporadic poetry before and even replied to the best-known mystical poetry of Ayatollah Khomeini in verse. The founder of the Islamic Republic’s famous line says: “I am taken with the mole on your lips, Ay Friend // I saw your ailing eyes and now I am sick, too.” To which Khamenei has replied: “You are a mole on the lip yourself! What are you taken with? // You cure all! How can you become sick?”

A Painful Frustration

Iran’s literary establishment has long been dominated by men and women who come from a secular background. These are the people that Khamenei’s Islamic Republic launched an open war against shortly after its foundation in 1979. Forty years later, the Islamist revolution has failed to bring about literary giants like those of the country’s past. This, despite the fact that millions of dollars are spent on nurturing pro-government cultural productivity. This must be a painful realization for Ayatollah Khamenei who, as a young revolutionary in the Mashhad of 1960s and 1970s, hobnobbed with some of the great writers of Persian literature and who takes much pride in his artistic taste.

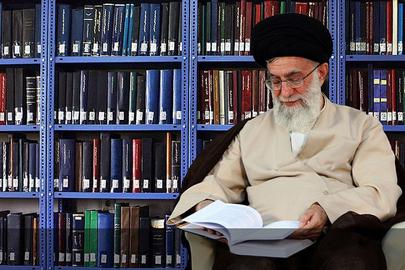

Every year, during the holy month of Ramadan, Khamenei gathers a group of pro-government poets, listens to their work being read or recited in a public forum and gives his opinion. He goes out of his way to appear to profess an expert opinion. Video footage of these meetings are broadcast widely and analyzed endlessly by pro-government media outlets. The Leader lavishes most of these poets with praise, but almost none of them get any attention from the country’s serious literati; their poems are usually shallow hagiographies around pro-government themes, the most up-to-date of which is praising Iranian soldiers who died fighting in Syria.

Khamenei is open about his supposed expertise. In 1991, when meeting a group of artistic creators, he said: “When it comes to cinema or visual arts, I don’t know much and am only a regular audience member. But in poetry and novels, I am more than just a member of the public.”

On another occasion in 1993, he said: “Even though I am very busy at work, it is thanks to God that I am not separated from books and I can never be. If anyone wants to remain fresh spiritually and culturally, there is no way other than keeping a relationship with books; this is akin to a relationship with an eternal river that always gives you something new.”

But such choreographed mediocre shows are unlikely to satisfy Khamenei. He must know that the real literary establishment scoffs at them and this must offend his artistic sensibilities. He has, thus, been at pains to establish his credentials with giants of contemporary Persian literature. When meeting a group of poets who had come to wish him well when he was recovering from surgery, Khamenei read a poem from Parvin Etesami, a pioneering female poet who died in 1941, just before the wave of New Poetry changed the country’s literary scene. The Leader complained that Etesami is usually overlooked in favor of the much more famous female poet Forough Farrokhzad, but was quick to add that he liked Forough too — something of a surprise to some since the latter is habitually known for her erotic poetry and for scandalizing many with her Simone de Beauvoir-esque lifestyle. On another occasion, Ali Damghani, head of the Iranian Academy of the Arts and a pro-Khamenei stalwart, claimed that Khamenei had met with Hushang Ebtehaj, a towering poet and a long-time member of the pro-communist Tudeh Party, which was brutally oppressed and almost completely annihilated by the Islamic Republic in the early 1980s when Khamenei was president. Damghani claimed that Khamenei knew Ebtehaj’s poetry very well and awed everyone by reciting it from memory.

Khamenei has also long tried to carve himself a place among the literary stars of his native province of Khorasan in northeastern Iran. The state media has also tried to concoct a mythical friendship between Khamenei and Mehdi Akhavan Sales who, like Khamenei, hails from Khorasan but, unlike him, is a recognized member of the pantheon of contemporary Persian poetry. The story of how Sales, also a one-time communist (like the vast majority of modern Iranian intellectuals), was close to Khamenei and purportedly wrote him poetry is one side of a narrative war. On the other side, critics of Khamenei claim that Sales actually refused Khamenei’s offer to become a courtier “poet of the revolution” in the early post-1979 years and purportedly replied: “Poets stand against power, not with power.” Sales, who died in 1990, is likely to have known Khamenei before the revolution and would have probably had a good relationship with a fellow Khorasani who shared his anti-Shah cause (Sales had been imprisoned twice under the Shah, once at the height of his pro-communist activities in 1949 and once more in 1966, when the Shah’s dictatorship was at its height of power). But there is no evidence that he supported Khamenei’s brutal theocracy, which established its power partially through severe censorship of the country’s literary scene.

The Dictator and World Literature

Khamenei’s claim to artistic expertise is not limited to Iran, as he also presents himself as a bookworm who knows his world literature. Throughout his decades in power, he has often expressed his literary opinion.

In 1993, he said he had read “thousands of stories from the best writers in the world” and was therefore able to “offer an opinion.” In 1997, he claimed to have read Jane Austen in original English, including her famed Pride and Prejudice. Mohsen Chiniforooshan, something of a cultural confidante to Khamenei who has headed some of the key cultural institutions in the country, said Khamenei was a fan of Russian writers including Anton Chekov, French writers such as Honore de Balzac and Romain Rolland and also Arab writers (as a trained cleric, Khamenei boasts a reading knowledge of Arabic.)

According to Chiniforoshan, Khamenei wishes that his revolution could produce someone like Rolland who could write a biography of Khomeini “and the great men of the revolution” that would rival Rolland’s account of Mahatma Gandhi. The Leader has gone on record praising not only Rolland but his Persian translator, Mohammad Ghazi, also a long-time communist who had to see many of his comrades go to jail under Khamenei’s reign.

One of the most curious literary standpoints of Khamenei relates to Soviet literature. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 is condemned in the official ideology of the Islamic Republic as materialistic and godless. Ayatollah Khomeini was a veteran anti-Marxist and anti-communist who said that the USSR was even worse than the US, which he had christened The Great Satan (he conveniently said so after he came to power, not when he needed the support of leftist opponents of the Shah.)

In Khamenei’s reading, however, the Russian revolution, while not worthy of his outright support, is regarded as something of a great event that gave rise to great literature, including Khamenei’s favorite And Quiet Flows the Don by the pro-Soviet Mikhail Sholokhov, who had the rare distinction of having won the Nobel literature in Literature in 1965 while being a member of the Soviet Union’s Central Committee of the Communist Party. Khamenei has called the book “one of the world’s best novels,” although he has curiously added that the first volume is better than the rest. Ironically, the novel has been twice translated to Persian, once by Behazin, a veteran communist, and a second time by Ahmad Shamloo, an anarchist-leaning poet who is perhaps the greatest Persian poet of the 20th century and a bete noire of the Islamist regime who did nothing to hide his hatred for the ruling mullahs.

In the same vein, Khamenei has criticized the Kiev-born novelist Mikhail Bulgakov for his “counter-revolutionary works” including Heart of a Dog or The Master and Margarita. Not coincidentally, the latter became one of the many anti-Stalinist works that filled the bookshelves of the critics of the Iranian autocracy in the heyday of the reform movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s. (Milan Kundera was another top favorite.)

Perhaps it is due to a similar reason that Maria Vargas Llosa hasn’t been so lucky with the Leader. According to Chiniforooshan, Khamenei has criticized the Peruvian writer’s The Feast of the Goat “from a technical point of view.” The 2000 novel focuses on the assassination of the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo and Llosa is a well-known opponent of the Latin American left and its literary icon, Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Aleksey Tolstoy is another Soviet writer favored by Khamenei, and the Supreme Leader was clear that he liked the famous Comrade Count because of the author’s association with the revolution. “[Tolstoy] is a very strong writer with very good novels, a writer of the Soviet revolution in whose work you can taste the new era,” Khamenei said in 1991.

Another Eastern Bloc writer praised by Khamenei is the Romanian Zaharia Stancu, president of the country’s Writers’ Union during the autocratic rule of the communist party there. Stancu’s work has also been made known to Persian readers by two translators, Shamloo and Parviz Shahriari, a communist of Zoroastrian origin who spent time in jail under the Islamic Republic. Speaking to a group of young people in 1997, Khamenei compared Stancu’s portrayal of German-occupied Bucharest and the resistance against it to the “occupation” of the “Islamic region, i.e. Middle East and North Africa.” “This occupation differs from the traditional military occupation,” Khamenei told his audience in this televised presence. “It is a total cultural economic and political domination that sometimes doesn't even need an occupier... much of Asia and Latin America suffers from the same.”

“The occupier is not the US government or this or that state. No, it is a social class; a class that directs the US and other governments,” Khamenei continued, speaking in somewhat conspiratorial and pseudo-Marxist terms. “What drives this effort is not a government. It is a class complex that, if we were to put a name on it, could be called Power-Seeking Masters of Gold who seek to dominate all the world’s natural and financial resources.”

And Khamenei has other favorite writers. Nineteenth-century French writer Stendhal is praised as a “master of story writing in the Western culture,” particularly due to his 1830 masterpiece, The Red and the Black, which supposedly shows the weak moral basis of the West. Another French writer, Roger Roger Martin du Gard, Nobel laureate in 1937, is noted for The Thibaults, which, according to Khamenei, shows the limits of godless humanist thinking. (Du Gard was a supporter of socialist humanism and the socialist leader Jean Jaures.)

What becomes clear after a thorough review of Khamenei’s literary takes is that, unlike the myth he propagates (and which is even propagated by many of his opponents), he is not much more than an amateur reader with a superficial liking for epic and spiritual themes in literature. The young revolutionary Khamenei of the 1970s likely harbored high literary ambitions. He hated the traditional mullahs he decried as “reactionary,” and wanted to politicize the clergy and move it to the left. A favorite writer of his was a leader of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, Sayyid Qutb, several of whose books Khamenei translated into Persian. Unlike Qutb, who was executed in 1966 by Egypt’s socialist president Gamal Abdel Nasser, Khamenei was to rise to power and is today one of the world’s longest-lasting rulers. Somewhere deep down, however, the ayatollah might wish he was to write two lines of poetry like those that have been written by authors who have been so brutally suppressed by his regime.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments