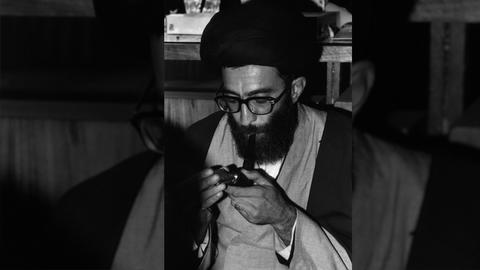

When Ayatollah Khamenei became Iran’s Leader in 1989, he was a member of the “right wing” of the Islamic Republic. This was a conservative and reactionary, but rather pragmatic, faction in comparison with the “left wing” of the Iranian regime, which was less conservative but more ideological in domestic and foreign policies.

The so-called right-wingers supported, for instance, less government intervention in economy, while being more in favor of the application of sharia law. They also endorsed a less radical perception in foreign policy and, compared to the left-wingers, put less emphasis on Iran’s confrontation with US allies in the region.

Ali Khamenei was not very close to the right wing when he became the president in 1981, but he gradually became closer to it due to his confrontation with certain figures on the left. The reason for this change was that during Khamenei’s presidency, the prime minister was Mir-Hossein Mousavi, an icon of the Islamic Republic’s left wing of the time, with whom Khamenei had widespread disagreements. These disagreements, first and foremost, resulted from Iran’s (former) constitution, in which the executive branch was mainly managed by the prime minister, rather than the president, who was officially the highest executive official.

It was under such circumstances that, at the end of his presidential term in 1989, Ali Khamenei had become a dedicated opponent to Mousavi and his allies, i.e., members of the left wing of the Iranian government.

Khamenei’s First Pragmatic Experience

When Ayatollah Khomeini died in June 1989, many foreign observers suggested that his death might result in more pragmatism within the Iranian regime.

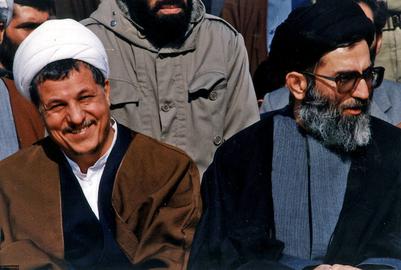

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the head of the parliament when Ayatollah Khomeini died, played a decisive role in Khamenei’s appointment as the new Leader. He literally guided the extraordinary session of the Assembly of Experts, which was in charge of appointing the new Leader, in such a way that Khamenei could become Ayatollah Khomeini’s successor. At that time, Rafsanjani, who was viewed as being the icon of pragmatism within the Iranian regime, exercised a great influence over the new Leader.

In his diaries, Rafsanjani emphasizes that Khamenei’s appointment as the Iranian Leader was welcome by the West. Rafsanjani writes on June 5, 1989: “The reports indicate that the Westerners are happy with Ayatollah Khamenei’s appointment, which they hope could lead to the rule of moderation and the isolation of the radicals.”

These comments were made a few months after the inaugural address of George H.W. Bush (senior), in which the new US president signaled that Iran’s help to free American hostages in Lebanon would bring about better relations between the two countries. He said: “Assistance can be shown here, and will be long remembered. Good will begets good will. Good faith can be a spiral that endlessly moves on.” These remarks sparked indirect contacts between Tehran and Washington, with the mediation of the UN, and finally resulted in the liberation of US hostages in Lebanon. Hashemi Rafsanjani coordinated all these efforts with the approval of Ayatollah Khamenei, who, at the beginning of his leadership era, was actively testing a pragmatic foreign policy experience.

But this experience did not result in Washington’s releasing Iran’s frozen assets in the US as Tehran wished. Washington refrained to do so because of Iranian operatives’ alleged involvement in new extraterritorial terrorist operations. As a result, George Bush’s initiative did not bring about any improvement in Iran-US relations, and even played an important role in Ayatollah Khamenei’s emerging distrust of pragmatic initiatives.

Isolating the So-Called Radicals

Some of Khamenei’s decisions in the first years of his leadership seemed to be in favor of isolating the less pragmatic and more radical figures within the Islamic Republic. Khamenei began to massively purge the members of the regime’s left wing, who were relatively more ideological and anti-American during Ayatollah Khomeini’s era. After Rafsanjani’s presidency began in October 1989, the new Leader and new president were in complete agreement when it came to eliminating the so-called left-wingers. At that time, Rafsanjani did not believe in any political openness, but wanted to open up the country’s economy and — to some extent — society, and to reduce tensions with the West, while many left-wingers strongly opposed his new policies.

In the first years of Hashemi Rafsanjani’s term, when Khamenei still felt he owed his leadership position to the president, the Islamic Republic adopted much more pragmatic policies compared with Khomeini’s era when it came to economic, diplomatic and social perspectives. However, the more Khamenei gained confidence in his new position, the more he became critical of Rafsanjani’s policies. At the end of Hashemi Rafsanjani’s first presidential term, Khamenei totally supported the president’s oppressive policies against the government’s political opponents, but he disagreed with a series of his economic, social and cultural policies. As a result, Hashemi Rafsanjani was forced to replace a number of his key ministers with more ideological and less pragmatist figures.

A number of the new ministers were in charge of economic affairs. Rafsanjani’s move toward free-market policies and privatization had led to widespread social dissatisfaction, which the Leader viewed as a potential security risk for the Iranian regime.

At the same time, many of Hashemi Rafsanjani’s former allies in the right wing of the Islamic regime became critical of Rafsanjani’s policies. They were especially against his administration’s approach to provide more social and cultural freedoms and to integrate the country’s economy to the international market, which weakened the traditional position of the right-wingers in Iran’s economy.

The IRGC, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, gradually became critical of Rafsanjani’s policies, too. Over the course of Ayatollah Khomeini’s era, the IRGC was closer to Rafsanjani than Khamenei. But when the latter became Iran’s Leader, he established very close relations with the IRGC commanders in order to use this powerful force to consolidate his power. The IRGC commanders were particularly concerned about what they believed to be Rafsanjani’s endorsement of Western economic and cultural values, which they rejected as a diversion from the Islamic revolution’s basic principles.

The 5th Majlis (Parliament) Experience

The split between the then president and his former right-wing allies deepened when a group of pro-Rafsanjani technocrats and politicians, who were previously united against their left-wing rivals, decided to end this alliance in the 1996 parliamentary election.

This decision, which was approved by Hashemi Rafsanjani, led to an overall confrontation between the pro-Rafsanjani forces and a spectrum of his powerful opponents, including many IRGC commanders and a number of Ayatollah Khamenei’s powerful appointees.

The pro-Rafsanjani forces did not win the 1996 parliamentary election, but they managed to form a powerful faction in the next parliament, the 5th Majlis of the Islamic Republic. Simultaneously, the new split within the right wing brought the pre-Rafsanjani forces closer to some of their former rivals in the left wing of the Islamic.

This new change gradually formed a new and unofficial alliance between the more pragmatic figures in the right and left wings of the Iranian regime. This alliance, which was not acceptable for Ayatollah Khamenei, finally paved the way for the unexpected victory of Mohammad Khatami in the 1997 presidential election.

This is the first of a three-part series on Ayatollah Khamenei’s transition from pragmatism towards a more ideological approach. In the next installment, we will review the “reforms era,” and its effect on the Leader’s perception of pragmatism.

Read other articles in the series:

Decoding Iran’s Politics: The Leader’s Public Appearances

Decoding Iran’s Politics: Long-term Planning in the Islamic Republic

Decoding Iran’s Politics: Controversy Over Tehran’s Regional Expenses

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments