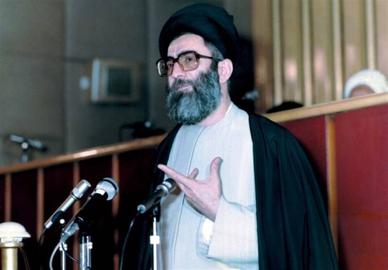

In 1981, when Ali Khamenei became president of the Islamic Republic, he was 42, the same age as Ruhollah Zam, the journalist that his government executed in December 2020. Three months from now, Khamenei will be 82, meaning he has been the head of the Islamic Republic for half of his life: eight years as president and close to 32 years as the Supreme Leader. He is among the very few in the last 500 years to have ruled a country for more than 30 years.

Throughout these years Khamenei has incessantly expanded his hegemony, directly and indirectly, over all affairs of state, and when he has blundered he has either pointed the finger at somebody else or has relied on the passage of time so that the incident will fade from memory. Of course, he has also enjoyed the collaboration of not only the media and the institutions under his control but also the so-called reformists and moderates, who never bring his blunders to the public’s attention.

A review of Khamenei’s performance in the second half of the 1990s reveal a few aspects concerning his style of leadership. Most of the details about this period come from the 1997 diaries of the late Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, former president and one of the most influential figures in post-revolutionary Iran. In that year, contrary to predictions, the reformist Mohammad Khatami won the presidential election. According to Rafsanjani’s diaries, many of those who met with him after the election told him they were worried about the “standing of the Leader” after Khamenei and his office’s dismal record when it came to misreading the electorate and the fact that, for all practical purposes, he had implicitly supported Khatami’s competitor. One can only assume that Khamenei himself knew well that he had committed a big mistake but was waiting for a chance to blame somebody else.

Election Results Khamenei Did not Want

In his diary entry for May 15, 1997, Rafsanjani writes about his meeting with Khatami’s associates, who complained bitterly about actions taken by “Friday imams, the Basij, the Intelligence Ministry and [the state-run] radio and TV.”

Two weeks earlier, following a speech by Khamenei, the same group, which included Mohammad Mousavi Khoeiniha, Mehdi Karroubi, Mohsen Nourbakhsh, Gholamhossein Karbaschi and Hossein Marashi, had met with Rafsanjani to consult with him as to whether Khatami should withdraw before the election took place. Rafsanjani, who was president at the time, dissuaded them. “I advised them against it and saidI would talk it over with the Leader,” writes Rafsanjani.

“In issues such as the presidential election, trust the clergy more than anybody else,” Khamenei had said in his speech, which was delivered two days earlier, on May 13. The clergy had been supporting Ali Akbar Nategh Nouri, Khatami’s conservative competitor in the presidential election. Khamenei’s speech was construed as the Supreme Leader’s support for Nategh Nouri.

The same night Rafsanjani met with Khamenei, who completely denied that he had been supporting one candidate over another and it was agreed that he would meet Khatami to convince him of his neutrality.

Two weeks prior to this, Ali Larijani, who was at the time the head of the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), had told Rafsanjani that he was worried because opinion polls showed that Khatami was gaining momentum and Nategh Nouri was losing it.

Before Larijani, Mohammad Yazdi, who was another Khamenei appointee and head of the judiciary, had expressed similar concerns. He complained to Rafsanjani that two other presidential candidates, former intelligence minister Mohammad Reyshahri and Reza Zavarei, were draining votes away from Nategh Nouri and hurting his chances of getting elected.

Nevertheless, just one week before the election and after another speech by Khamenei delivered during a meeting with IRIB, Khatami’s associates once again went to see Rafsanjani and once again raised the subject of Khatami’s dropping out of the race, a move that was again seen as support for Nategh Nouri.

Rafsanjani delivered a sermon at Friday Prayers in Tehran and spoke against “election fraud”. Khatami supporters were heartened by this speech but it irritated Nategh Nouri supporters, and especially IRIB’s management. Rafsanjani wrote in his diary he had noticed their “irritation” by the way IRIB had televised his sermon.

Hassan Rouhani’s reaction to these events is also noteworthy. At the time he was first deputy speaker of the parliament and he told Rafsanjani he was worried about the “potential consequences” of statements Khamenei had made. According to Rafsanjani, Rouhani said that Khamenei had taken on “clearly one-sided positions” and he worried that “if people do not vote in accordance with his views it will strike a hard blow to the regime.”

In his entry for May 20, 1979, Rafsanjani writes that Khamenei “still believes that Nategh Nouri is ahead but he thinks that there will be a runoff.” On the last day of the campaign the newspaper Abrar quoted Ayatollah Mohammad Reza Mahdavi Kani, an influential clergyman who was later appointed as the chairman of the Assembly of Experts: “I think the exalted Supreme Leader favors Mr. Nategh Nouri.”

An Overwhelming Rejection of “Khamenei’s Candidate”

Eventually the election was held on May 23 and a day later it was announced that Khatami had won by 70 percent of the votes.

Four days after the election, Ebrahim Amini, who was then deputy chairman of the Assembly of Experts, visited Rafsanjani and told him he was worried that the “the standing of the Supreme Leader has been hurt” because of “actions taken in regard to presidential and parliamentary elections and the issue of religious authority” and also because of “the mismanagement that has damaged the credibility of the clergy in the election”.

On June 13, associates of Khatami told Rafsanjani they were unhappy about the results of the meeting that they had had with Khamenei and they were afraid that Khatami’s upcoming administration was going to face obstructionism and obstacles. In the following days, other officials and political figures expressed similar concerns to Rafsanjani.

Rafsanjani’s notebook for that year bears evidence that Khamenei’s overwhelming victory in the election and voters’ disregard for his thinly-disguised support for Khatami’s rival was interpreted by many as damage to the status of the Supreme Leader. Most likely, Khamenei himself understood this and was waiting for a chance to launch a counteroffensive. He found his chance less than six months later, after a speech delivered by Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, once Khomeini’s heir apparent and who fell out of favor for advocating civil rights and his opposition to the mass execution of political prisoners in 1988.

In the speech, delivered on November 14, 1997 to mark the birthday of Ali, the first Shia Imam, Montazeri openly criticized Khamenei and the power establishment under his command. Khamenei’s supporters immediately turned this speech into a full-fledged scandal, which led to the occupation and destruction of Montazeri’s congregational prayer hall, “spontaneous” marches and protests against him. Eventually, Montazeri was placed under house arrest for five years.

Velayat-e Faqih, the “Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist,” said Montazeri in his speech “is in our constitution but this does not mean that the faqih is the absolute ruler, because then the republic becomes meaningless.” He added that, he had sent a message to President Khatami, and told him: “you cannot do your job the way you have been doing it...If I were you I would go to the Leader and tell him ‘your station is safe and people have respect for you, but 22 million voted for me and, when they were voting, these 22 million knew that the Leader of the country supported someone else.’”

Montazeri went on to explicitly question Khamenei’s credentials as an ayatollah and religious authority.

Dismissing the “Nobodies”

Less than two weeks after Montazeri’s speech, when the Supreme Leader was confident that the streets were under the control of the mobs his supporters had mobilized to intimidate Montazeri and anybody who dared to support him, Khamenei delivered a speech to a group of paramilitary Basijis, attacking “a few simpleton clerics” who he described as “nobodies” and, without naming him, called Montazeri a “hapless” individual.

In his speech, Khamenei repeated that the Leader, i.e., himself, brings people together and prevents divisions. When the “enemy” tries to dissuade people from going to the polls, he said, “it is the Leader who guides the people and tells them that voting is a duty. Then people gain confidence, participate in the election and create a magnificent epic...People listen to the Leader.”

Of course, Khamenei knew well that six months earlier, people might have been “listening to the Leader,” but they still took action that was the exact opposite to what he had told them to do. But the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, of course, had no intention of listening to the people. As associates of Khatami had feared, Khamenei spent the next eight years obstructing any attempt at reform using institutions under his control. When none of Khatami’s campaign promises were realized, people lost their trust in reform and reformists.

However, the reformists, including Khatami himself, played their role in the successful attack on the democratic process and civil society waged by Khamenei because they all agreed on one thing: the “dignity” of the Supreme Leader’s position must be respected at all times.

Khamenei lost the battle of the election, but won the war for uncontested power at great cost to Iran: the weakening of the most basic foundations of democracy and civil society and the people’s despair regarding any possibility of meaningful reform.

Related Coverage:

Disenfranchising the Parliament, Part One

Disenfranchising the Parliament, Part Two

Disenfranchising the Parliament, Part Three

Disenfranchising the Parliament, Part Four

The Overnight Ayatollah: Khamenei's Fight to Become a Spiritual Leader

Why is Khamenei Still Trying to Prove his Legitimacy as Leader?

Decoding Iran's Politics: Khamenei's Move Away From Pragmatic Politics (Part One)

Decoding Iran’s Politics: Khamenei's Move Away From Pragmatic Politics (Part Two)

Decoding Iran’s Politics: Khamenei's Move Away From Pragmatic Politics (Part Three)

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments