The history of World War II is studded with the names of heroic individuals and organizations who risked life and limb to protect Jews and other minorities from the horrors committed by the Nazis and their supporters. Regrettably, there were far too few. One such name, which surfaced only as the 20th century was drawing to a close, is that of Derviš Korkut: an Islamic scholar, educator and long-time curator of the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina , who never disguised his objection to the atrocities taking place around him during the war – or failed to act against them when required. This singular individual not only took in and hid an orphaned Jewish girl at the height of the Holocaust in wartime fascist Croatia, but saved an array of priceless Jewish manuscripts from confiscation, among them the famous Sarajevo Haggadah: a 14th-century tome which Derviš Korkut rescued from almost certain destruction by tucking it into the waistband of his trousers when the fascists came knocking. Due to political contingencies in the years that followed, the story of this man, who was posthumously named by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations, was very nearly lost for good.

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was formed on December 1, 1918 after World War I as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. It was a complex union, bringing together several different ethnic groups under one administration, and grew only more so as inter-war pressures – including economic crisis and the rise of nationalism – prompted the Serb and Croat ruling elites to consider re-organizing the country. In August 1939 the then-deputy prime minister and leader of the Croatian Peasant Party, Vladko Maček, signed a landmark agreement to decentralize the central government and create an autonomous Croatian province, the Banovina of Croatia, which included parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This would prove to be a prelude to the collapse of Yugoslavia two years later, after the invasion of Nazi Germany and its allies in the spring of 1941.

At the time, as in other parts of Europe, antisemitism was gaining ground in Yugoslavia. The government had begun to implement anti-Jewish legislation that would adversely impact the country’s 75,000-strong Jewish population, some of whom were refugees from Germany, Czechoslovakia and Austria. One new law banned wholesale enterprises owned or co-owned by Jews, while another introduced a quota system for Jewish students in schools.

In response to this, in 1940 a group of Yugoslav intellectuals published a collection of papers intended as a rebuttal, entitled Naši Jevreji : jevrejsko pitanje kod nas: Zbornik mišljenja naših javnih radnika (Our Jews: The Jewish Question with us: A Collection of Public Workers’ Opinions). This volume, edited by two Yugoslav journalists, Mića Dimitrijević and Vojislav Stojanović, contained more than 20 papers by a diverse selection of Yugoslav lawyers, journalists and writers. They engaged with ongoing public debates about the “Jewish Question” in Yugoslavia and strongly opposed rising antisemitism in the country.

The sole Muslim who contributed to the series was a man named Derviš M. Korkut. The title of his submission was straightforward: Antisemitizam je stran muslimanima u Bosni i Hercegovini (Antisemitism is Foreign to the Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina).

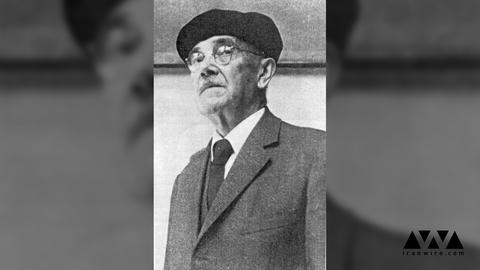

Derviš Korkut was a remarkable figure whose efforts to protect both Jews and their culture during World War II came to light more than a decade after his death and fall from grace in the eyes of the state. Born in Bosnia in 1888, he had pursued his higher education in Istanbul, Turkey and the Sorbonne in Paris, France, becoming a passionate theologian who was fluent in Turkish, Arabic, French and German. He began his working life in 1916 as a religious teacher, also serving as a military imam during World War I and later heading up the Muslim section of the Yugoslav Ministry of Religions from 1921 to 1923. From 1927 until 1929, he worked as a curator and librarian at the National Museum in Sarajevo. This was followed by a stint as an aide to the Mufti of Travnik, his place of birth, and from 1933 to 1936 as editor-in-chief of the Glasnik (The Herald): the official organ of the Islamic community of Yugoslavia. From 1939 onwards Korkut would return to his former role as curator of the National Museum, which was a treasure-trove of artefacts related to the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

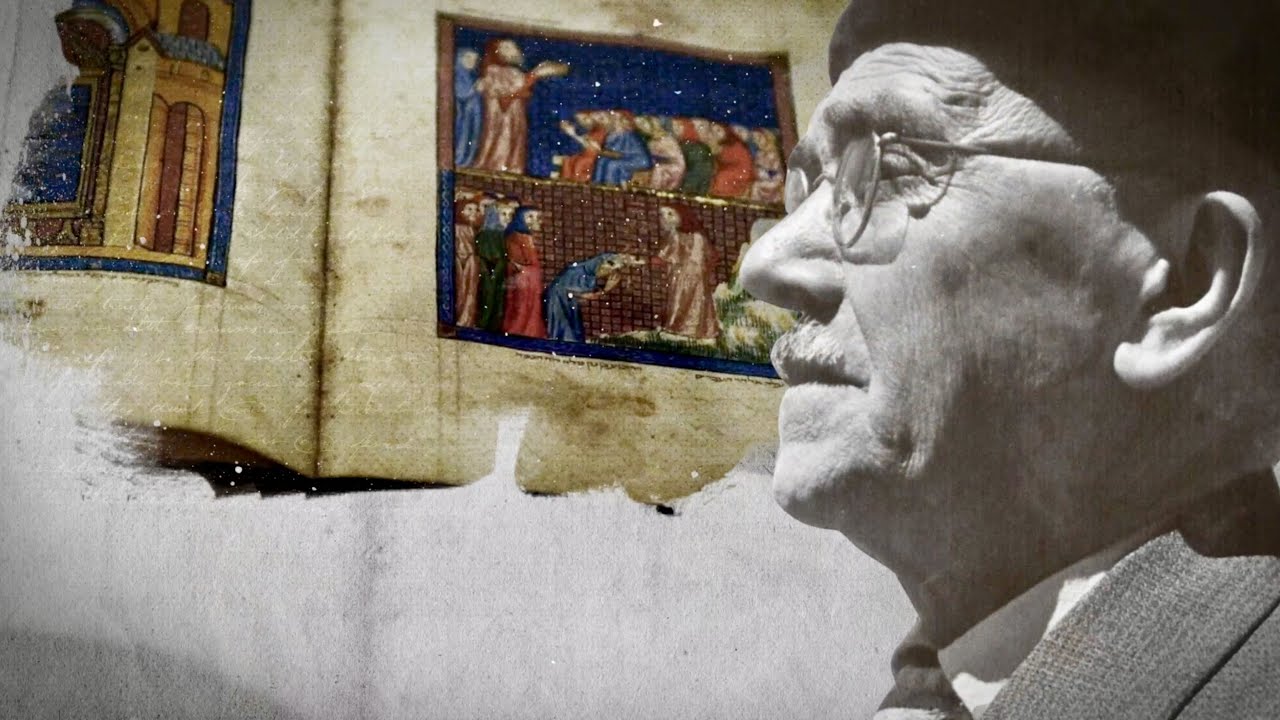

One of the Museum’s most precious acquisitions was the Sarajevo Haggadah, an illuminated 14th-century codex commemorating the biblical Exodus read by Jews at Passover. Originating from Barcelona, Spain, it was brought to the Ottoman Empire by exiled Sephardic Jews who were expelled from Catholic Spain during the Inquisition. It eventually fell into the hands of a young Sarajevan Jew, Joseph Cohen, who sold it to the newly-established Imperial National Museum of Bosnia in 1894. Through Korkut’s efforts, this and other priceless artefacts were saved from almost certain destruction during the Nazi occupation of the city.

On April 6, 1941, a year and a half after the outset of World War II, Nazi Germany and its Allies invaded and occupied Yugoslavia and proceeded to dismantle the country. In Serbia, the Nazis established a puppet administration led by Milan Nedić. Racist laws were implemented against the Jewish and Roma population, with Serbian collaborationist police aiding the Gestapo and other German occupation authorities. Some 14,500 Jews were murdered in Serbia, which in May 1942 became one of the first territories in Europe to be declared “Judenfrei” – free of Jews – by the Nazis. This was part of the German plan to systematically murder Jews across the continent.

In the Western part of Yugoslavia, another Nazi puppet state, the “The Independent State of Croatia,” was formed incorporating Bosnia-Herzegovina within its territory. It was governed by the Ustasha, a Croatian fascist and ultranationalist movement led by Ante Pavelić, and it immediately introduced laws against the Jews, Serbs and Roma people. The country was occupied by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, which guaranteed its security, but the Ustasha had considerable autonomy and conducted a brutal genocidal campaign within the territory, murdering hundreds of thousands of Serbs, Jews, Roma people and political opponents. The Ustasha murdered more than 30,000 Jews both in camps that they ran themselves in Croatia and by deporting them to Nazi camps in German-occupied Poland.

The targeting of minority populations in the early days of the Ustasha regime was cause for consternation for some Bosnian Muslim intellectuals, including Derviš Korkut. Bosnian Roma were primarily Muslims, and according to the American scholar Emily Greble, “Sarajevo’s Muslims recognized that the racial classification of Roma had broader implications for Muslims in Croatia. In a state where racial status determined one’s right to live, Muslims were justifiably wary of any ideology that defined any part of their religious community as an inferior group. They realized that if the new rulers could label some Muslims, in this case Roma, non-Aryan, nothing prevented them from reclassifying other Muslims in the future.”

Korkut was one of a consortium of elite scholars, among them Dr.Sačir Sikirić, Dean of the Higher Islamic-Theological School in Sarajevo, Dr. Hamdija Kreševljaković, a historian from the Croatian Academy of Arts and Science, and Mehmed Handžić, director of the Gazi Husrev-bey Library in Sarajevo, who together published a paper that proved, using German sources, that the Roma were in fact Aryans and “white Muslims” who should not be targeted. They cited the works of Leopold Glück, a Polish Jewish doctor and anthropologist who had conducted research on the Roma population in the region. The report was filed to the authorities as and as a consequence, the puppet Ministry of the Interior ordered the suspension of the persecution of the Roma people.

Korkut also publicly supported more wide-ranging initiatives against Nazi discrimination. In October 1941, he was among the 108 prominent Bosnian Muslims who drew up and signed the Sarajevo Resolution: a public condemnation of the atrocities committed by the Nazis and Ustasha, and the distancing of Muslims from these crimes. That same month, Derviš Korkut was approached at the National Museum by a Sephardic Jewish leader in Sarajevo, Dr. Vita Kajon, who suspected that he would soon be targeted by the fascist authorities and entrusted a box of Sephardic Jewish manuscripts to his friends. Fearing that the manuscripts would be looted or intentionally destroyed, Korkut logged them in the Museum’s archival register as “Archiv der Familie Kapetanović - Türkische Urkunden” (The Archives of the Kapetanović Family - Turkish Manuscripts). By intentionally registering them under a false title, Korkut managed to preserve a number of these important documents. Dr. Kajon was deported to the Croatian concentration camp of Jasenovac shortly afterwards and died there in 1942.

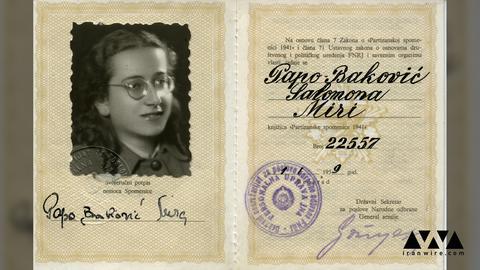

Then one day in April 1942, an acquaintance of Korkut’s came to the Museum with a young Jewish girl in tow, whom he had found in a park in Sarajevo. The girl, Mira Papo, was alone. Her parents had been sent to a concentration camp earlier in 1941 and she had escaped to the forests, where she joined a Yugoslavian communist partisan resistance group. Decimated by Nazi security forces, the group had ordered Mira and other young stragglers to return to Sarajevo.

Derviš Korkut took Mira in without hesitation, bringing her to his home and telling his wife, Servet, that she would be staying with them for a while. They dressed her in Muslim clothing, called her Amira and presented her as a Muslim servant from Albania who did not speak Bosnian. In this way Papo was kept safe and in August 1942, Korkut managed to arrange false identification documents for her, sending her to a safe Italian-occupied coastal region where she lived out the rest of the war.

Earlier on in 1942, Korkut had been at his workplace one day when word came that a high-ranking Nazi official, Johann Fortner, was coming to visit the Museum. In addition to commanding an army division Fortner oversaw the Black Legion, a Croatian fascist regiment responsible for the murder of many Serbs and Jews as well as members of the communist resistance movement. On hearing of the potential visit, Korkut immediately asked the Museum’s director, Jozo Petrović, for the keys to the basement safe. He unlocked it and took out the Sarajevo Haggadah, one of the Museum’s most valuable treasures, and hid it in the waistband of his trousers.

After arriving and touring the museum, General Fortner demanded that Korkut and his colleagues give him the Haggadah. Accounts of the exchange that followed vary – it is thought that Korkut told Fortner that the Haggadah had been taken by some other Nazi officers earlier that day – but one way or another, Fortner left without the precious tome in his possession. Korkut then brought the Haggadah home concealed under his coat, after which he gave it to a trustworthy imam at a mosque in a remote mountain village for protection.

Korkut’s principles and tacit resistance to the occupation would later get him into trouble at the Museum. The Museum’s original director, Jozo Petrović, was Korkut’s friend and supported him in his activities. But Petrović was removed from his position in late 1943 and replaced by Vejsil Čurčić. In March 1944, Čurčić asked for the library and archives to be handed over to an associate of his. Fearing that the Ustasha administration wanted to destroy the library’s rich collection of old and rare manuscripts, Korkut declined and then delayed the handover, citing legal complications. This led him to be viewed as untrustworthy, and in 1944 he received an order, signed by the Ustasha leader Ante Pavelić himself, to be transferred to work as a librarian at the Zagreb National University Library. Before the transfer took place, Korkut was warned by friends that this was a ruse to have him and his family detained and sent to the Jasenovac concentration camp. Korkut quickly took sick leave and went into hiding along with his family in Sarajevo, where they remained until it was liberated by partisan forces in April 1945.

After the war, Korkut returned to work at the Museum and the Sarajevo Haggadah was returned to its home institution. But he found himself at odds with the new communist government, whose hostility to religion was a stance he could not agree with. At the Museum, Korkut met with the British consul in Sarajevo and asked him to intervene with the victorious Allied powers to provide international legal protection for Yugoslav Muslims, similar to the provisions made for minorities in the Treaty of Saint-Germain of September 1919, which preserved minority rights in inter-war Yugoslavia and other parts of Europe.

In 1947, despite all his efforts to preserve Jewish lives and heritage during World War II, Korkut was arrested on trumped-up charges and tried for collaboration with the Ustasha and the Nazis. The new communist system frequently used fabricated charges such as these to eliminate its opponents and those who did not support the new ideology. In a short, rigged show trial together with several prominent Bosnian intellectuals, Korkut was sentenced to eight years of hard labor in prison. After his release, Korkut took up a new post at the Sarajevo City Museum, where he worked until his death in 1969 at the age of 81.

As a convicted “enemy of the state,” Derviš Korkut’s achievements in saving the Jewish manuscripts, the Sarajevo Haggadah and Mira Papo lay dormant and unknown until the Bosnian War in the early 1990s. In 1994, Mira Papo, now Mira Baković and living in Israel, wrote a letter to Yad Vashem and told for the first time the story of Derviš and Servet Korkut. As a consequence, both were recognized as Righteous among the Nations on December 14, 1994.

The bond between the Korkuts and the Bakovićs would continue in years to come. In 1999, Korkut’s daughter Lamija, who was married in Kosovo, escaped the Serbian onslaught and sought refuge in Skopje, Macedonia. She appealed for help from the local Jewish community and showed them her parents’ Yad Vashem certificate. The ensuing effort to transport the Korkuts safely to Israel sparked international media coverage – and caught the attention of Mira’s son, Davor. Soon Lamija and her family were safe and on a plane to Tel Aviv. On arrival at the airport, Davor was waiting to surprise them.

Half a century later, the story of Derviš Korkut remains an inspiration to all. This was a man who, when the time came, did what was right regardless of the consequences.

This article was produced by IranWire as part of The Sardari Project: Iran and the Holocaust, a project of Off-Centre Productions and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Read other articles in this series:

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments