The following is the full text of IranWire’s new report on the story of Covid-19 in the Islamic Republic of Iran during 2020. Only the Trenches Have Changed draws on our own online coronavirus “chronology” published throughout the year, as well as expert analysis and interviews with public health practitioners from around the world. The report seeks to show the impact of Iran’s dominant governance model on the long trajectory of the epidemic, and to explain to less familiar readers why Iran has been so badly-affected by coronavirus.

You can also read the report in a pdf viewer or download it here.

Written by Hannah Somerville, with additional reporting by Shahed Alavi and Pouyan Khoshhal.

**

Only the Trenches Have Changed

Health policy and practice in Iran during Covid-19

A report by IranWire

Introduction

By every conceivable measure, Iran has experienced the most catastrophic outbreak of coronavirus in the Middle East. At the time of writing the officially-reported number of domestic Covid-19 infections and deaths stood at 1.2 million and 55,650, while independent analyses place the real death toll at several times this figure.

To understand why the crisis has been so severe in Iran we are compelled to take a long view of the way the Islamic Republic of Iran has run its affairs ever since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Health policy is never formulated in a vacuum, and in 2020, the cascade-effect of distinct political, ideological, social and logistical contingencies shaped both Iran’s official response to Covid-19 and the immediate and long trajectories of the epidemic.

Throughout last year IranWire sought to report any and all known coronavirus-related developments in Iran as they happened. Our daily “chronology” took in official reports, statements by public figures, and anecdotal and documentary evidence received by our journalists about the evolving situation on the ground. By the end of the year IranWire had published more than 300,000 words on this subject online in English and in Persian, which stands now as an important, if incomplete, document of the disaster Iran has faced.

News, as the cliché goes, is only the first rough draft of history. This report now aims to present a more condensed and contextualised version of the story so far, as reported by IranWire and our colleagues and partners in the fields of journalism and human rights in 2020. We begin with an overview of how health policy is formulated in Iran and the challenges the health sector was experiencing before Covid-19, before offering a fresh examination of both how and why events unfolded the way they did last year.

More tentatively, we attempt to shed some light on the human cost of vacillating approaches to non-pharmaceutical interventions during the pandemic, as well as disparities in health provision, at the level of provinces. We base our reading of the situation in localities on mortality data published by Iran’s National Organization for Civil Registration in winter 2019/20, spring 2020 and summer 2020, as collected and analyzed by a consortium of scholars in the UK, the US and Iran who generously shared their results with us for this report.

This re-reading of Iran’s response to Covid-19 is interspersed with observations on those of other countries around the world, in the hope that lessons may be learned for the benefit of Iran and the global community. Based on recent publications, detailed at the close of this report, parts of the Iranian government now appear to be reflexively engaged in the same.

Our heartfelt thanks to Dr Kaveh Khoshnood of the Yale Institute for Public Health, Dr Ali Arab, statistician at Georgetown University and Amnesty International US board member, and Katherine Hignett of the Health Service Journal, for their support and guidance. We are also grateful to the doctors and researchers interviewed for this report, and most importantly, to the multitude of individuals inside Iran whose bravery permitted us to cover this ongoing calamity in some depth over the course of 2020. This report is dedicated to them.

A Caveat

This report makes extensive use of qualitative as well as quantitative sources, particularly in its reading of the state of the Iranian health sector and mortality rates. Because these figures mainly stem from Iranian sources, they should always be approached with a measure of scepticism.

Iranian sources can be unreliable for a multitude of reasons. Institutions in Iran have been observed to provide multiple, parallel datasets that fundamentally disagree with each other, a problem that was observed to have exacerbated during the tenure of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from around 2007 onward [1]. This is quite possibly by design, for strategic purposes, rather than by accident, for practical reasons.

Figures provided to the World Health Organization come from different sources and are disputable even inside Iran. Death registrations published by the Civil Registrations Organization have fluctuated in the past by up to 100,000 deaths a year – to the extent that even natural disasters in the 1990s had a barely-discernible impact on seasonal all-cause mortality – though they seem to have stabilized since around 2015.

Based on qualified advice we have tried to rely where possible on sources that use the output of the Statistical Center of Iran as a basis. But the sources the Statistical Center draws on have diversified in both their nature and data-gathering methods particularly since the Ahmadinejad era, so even the figures reported by this body are not totally stable.

Iranian researchers seem to recognize this – hence, perhaps, the prevalence of published meta-analyses in Iranian scholarly output that draw on a range of different sources instead of one dataset. But these studies in turn may not be wholly reliable depending on the institution to which the author belongs (such as the Iranian Universities of Medical Sciences, which fall under the purview of the Ministry of Health).

Figures cited in this report should never be treated as incontrovertible fact but rather as indicative of general trends. This is particularly the case where they seem to agree with each other when taken together, as some of our sources appear to. The learning comes, rather, from scrying through them all.

Prologue I: Governance and the Supra-State

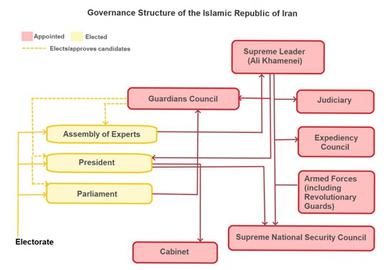

The Islamic Republic of Iran was established by a popular revolution in 1979 that overthrew the pro-Western, modernizing Shah of Iran. The country now operates as a theocracy, mandated by the principles of Twelver Shia Islam and enforced by an extensive military and security apparatus that still cleaves to the original revolutionary principles of 1979.

The Supreme Leader is the most senior spiritual and political authority in Iran, at once the head of and dependant on the support of an elite clerical caste who can enshrine new laws in accordance with the long-contested Khomeneist principle of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist). Unelected state institutions have extensive control over decision-making by Iran’s thus-compromised democratic components, including the elected president, executive and legislature. The Guardians Council, for instance, comprises senior Shia clerics, jurists and constitutional experts who can approve MPs or veto Acts of Parliament based on their adherence to Islamic law.

The Islamic Republic’s revolutionary-Islamic ideology is enforced at home and exported abroad by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a military organization that commands untold swathes of economic and political influence, and whose leaders are appointed by the Supreme Leader. The IRGC is supported inside Iran by the paramilitary Basij, the police and the intelligence services. As such, ideological and material exigencies of the clergy and the IRGC, and the caprices of the now-ageing Supreme Leader, have a direct and formative bearing on what decisions can practicably be taken by elected officials in Iran at a given time. This includes during a public health emergency.

Forty years have now passed since the Islamic Revolution. But the Iranian supra-state has yet to shed the sense of insecurity typically observed in authoritarian regimes in their immediate post-revolutionary periods. Due perhaps to the singular combination of misfortunes Iran and the Iranian people have experienced since 1979 – from the eight-year war with Iraq to economic sanctions, natural disasters to mass emigration and youth disenfranchisement – the regime remains in the “consolidation phase” and is near-pathologically preoccupied with reinforcing its legitimacy and manufacturing or forcing the appearance of domestic consent.

The state continuously seeks to re-establish itself through the triple-pronged approach of religious piousness, aggressive revolutionary propaganda and violent coercion. Hundreds of Iranians every year are arrested, tortured, jailed, disappeared and executed by the security agencies, with the oversight of the Revolutionary Courts, a relic of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Policymaking as well as criminal justice is colored by the “national security imperative”, in which non-security issues are approached through a security lens, because of underlying regime insecurity.

Securitization and the enforcement of revolutionary-Islamic ideology in Iran both become more apparent in times of intensified threat to regime stability. In January 2020, for example, when Iranian students protested the downing of a Ukrainian Airlines passenger plane by the IRGC at a time of heightened US-Iran tensions, the Iranian supra-state arrested, sentenced to lashes and jailed individual protesters for up to eight years on the pretext of national security.

So it was with the pandemic. Precisely because Covid-19 posed a direct threat to Iranian lives and livelihoods, it was framed as a security threat prior to being recognized – by degrees, and with lethal tardiness – as a health issue. Entrenched compulsions on the part of state actors toward Shia orthodoxy over medical science, and ideology over pragmatism and expert governance, clouded the official response to the pandemic and cost lives.

This was compounded by the fact that even after decades of laudible efforts toward universal health coverage in Iran, the health system was neither prepared nor robust enough to handle an epidemic of the scale it has faced. Of course, it should not have had to have been.

Prologue II: Health Provision in Iran Before the Pandemic

In the four decades since the Islamic Revolution, successive governments have worked toward achieving something approximating universal health coverage in Iran. Much of this has focused on “horizontal justice”: establishing equitable access to health resources to patients regardless of their material circumstances or physical location.

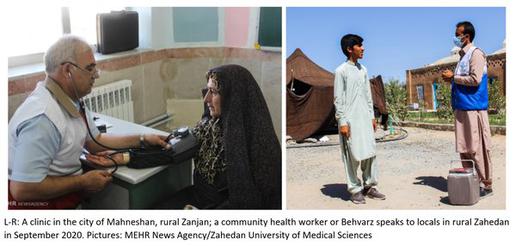

From the mid-1980s the Iranian state embarked on a landmark program to provide access to primary healthcare in every district across the then 24 – now 31 – provinces. Some 17,000 urban and rural “health houses” were established in localities where trained medical staff could provide services such as vaccinations, family planning and child healthcare to isolated communities. Over time, this and a prevention-based approach to health education have led to improved health outcomes across Iran according to several key indicators: average life expectancy, for instance, reached 76 in 2016, with infant mortality at an all-time low [2].

However, there remain serious weaknesses in the Iranian health system that last year would affect its ability to manage the coronavirus epidemic. Part of this is, as mentioned, related to governance and the influence of the supra-state on decision-making by politicians.

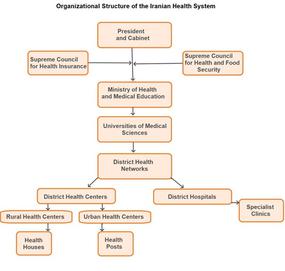

The Ministry of Health is formally responsible for setting the governing policies and protocols of public and private health providers. These are co-ordinated in the provinces by the heads of ministry-backed Universities of Medical Sciences at teaching hospitals, and subsequently delivered to communities with the oversight of district health networks.

However, as Dr Rouzbeh Esfandiari, a former emergency physician in Tehran and southeast Iran, explains: “Decisions about health in Iran are made by the Health Ministry, but they can’t actually make decisions independently.” [3] Instead, he says, the Ministry must consider “other factors”: chiefly socio-economic restraints and the needs of unelected branches of the state.

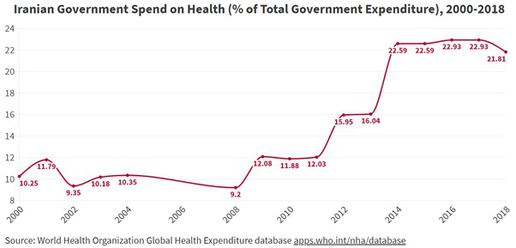

Health resourcing in Iran has recently come under considerable strain. For a decade now the government has ploughed unprecedented quantities of money into the health sector, with 23 percent of the budget spent on health in 2017 compared to 9.2 percent in 2008. [4] But this still only amounts to around US$245 per person per annum, and the cost of healthcare is now far outstripping the amount the government is able to spend on it.

In 2017, for instance, some 8.7 percent of Iranian GDP was reportedly spent on health [5]. But the impact of sanctions on the commercial sector, internal corruption and the collapse in the value of the rial has seen Iran’s GDP shrink by almost 10 percent last year alone, while inflation last year stood at 39.91 percent: the highest level recorded in 20 years [6].

Irregular procurement and corruption in the Health Ministry have simultaneously wasted public funds and stymied cost-effective purchasing. “There have been improvements to research and diagnostics in Iran over 40 years,” Dr Esfandiari says, “and one is that some medications can now be produced inside Iran. But there are still shortages because they go to the black market. For instance, each hospital has a specific quantity of remedesevir [an anti-viral drug that has been used in Iran to treat Covid-19 symptoms] it should receive. But you can also find these same vials of remedesivir on the streets. How is this possible?.” [7]

Dr Esfandiari also notes that in times of medication and equipment shortages, health officials have historically been quick to point to international sanctions as the cause rather than poor procurement decisions: “They could import medications such as the flu vaccine,” he says, “but they always have excuses as to why they cannot.”

The US Treasury’s Office for Foreign Assets Control has specific exemptions for health, medical and humanitarian supplies built into its ongoing sanctions program. But Human Rights Watch points out that renewed sanctions are nonetheless likely to have deterred at least some international banks and providers from participating in transactions with Iran [8].

In all probability a combination of the (albeit unintended) knock-on effect of sanctions, stockpiling and the government’s reluctance or inability to meet the costs of provision are responsible for now-severe shortages of critical supplies in Iranian hospitals, from diabetes medication to cancer drugs and critical care beds.

This has inevitably had an impact on health outcomes. Though solid data on this topic is sparse, an overview of published Iranian studies for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 found deaths from non-communicable diseases in Iran had risen sharply over the past decade: between 2009 and 2019, deaths from stroke are assessed as having increased by 18 percent, from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by 41 percent and linked to diabetes by up to 81 percent [9]. Figures reported to the WHO also state that cardiovascular disease accounted for 46 percent of all deaths in Iran compared to a world average of 31 percent. Steep increases in medicine prices have also recently affected millions of patients with complex and chronic illnesses. Many of these people are the same who, in 2020, became especially vulnerable to Covid-19.

Iran’s sixth five-year National Development Plan for 2016 to 2021 required the Ministry of Health to establish what it termed the “Universal and Comprehensive Health Care System”: a transformation of the health service that would prioritize prevention over treatment in line with now-recognized good practice in many developed countries [10]. The model focused on primary care at the level of communities, with GPs, family doctors and nurses able to refer more complex cases to specialists if necessary using a newly-established electronic healthcare record system.

While laudible, this has not changed the fact that people in urban and developed areas of Iran still appear to enjoy much better access to acute healthcare facilities when they need them. Some 75 percent of Iran’s 83.9 million-strong population lives in cities, and the size of local populations, as well as the bargaining power of local politicians, have been shown to play a key determining role in the allocation of government-run secondary care resources.

If map fails to load, refresh your browser or click here

Almost a third of the country’s 921 hospital settings are understood to be concentrated in the major cities of Tehran, Shiraz, Tabriz, Esfahan and Mashhad, where 20 percent of the Iranian population resides [11]. The Statistical Center of Iran records that there were 155 active hospital beds per 100,000 population in 2017 [12] and bed density varied significantly between provinces, with 217 beds per 100,000 people in Tehran but just 99 per 100,000 in the deprived province of Sistan and Baluchistan [13]. Concurrently, ICU beds also appear to be unevenly distributed across the country; one study found that in 2014 there were 8.4 ICU beds available per 100,000 people in the wealthy city of Semnan, and 6.5 per 100,000 in Tehran - but just 2.5 per 100,000 in Hormozgan, the country’s fifth poorest province [14].

Even within cities, acute settings seem to be concentrated in wealthier neighborhoods. A 2019 survey of five densely-populated Iranian cities found that 70.6 percent of hospitals were located in the neighbourhoods with the highest amount of residential floor space per capita [15].

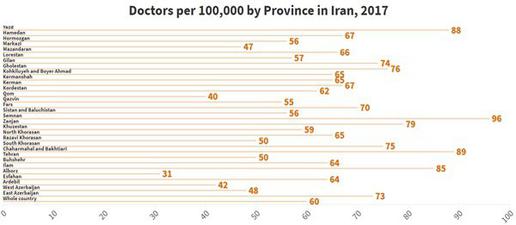

Because of the emigration of many health workers in the past decade [16], staff shortages are now also affecting the health sector’s ability to adequately support patients. Based on data submitted to the WHO, Iran had 15.4 doctors, 21.3 nurses, four dentists and three pharmacists per 10,000 population in 2018 [17]. Figures recorded by the Statistical Center for 2017 also strongly suggest there is an unsuitable distribution of physicians at Universities of Medical Sciences across the provinces – standing at 9.6 per 10,000 in Semnan, for example, compared to just 3.1 per 10,000 in Alborz [18] – while a multitude of surveys by Iranian scholars show nationwide shortages in areas such as anaesthesia, radiology and general surgery [19].

Telemedicine could be a potential solution. Patients’ being able to speak to doctors via video-conferencing can address urban-rural disparities by removing the need for doctors to be permanently located in remote territories, and it has been deployed to this effect in other countries such as India. During Covid-19 it would also have removed the need for infectious individuals to leave quarantine to be assessed by a physician.

Before the pandemic, however, telemedicine was not widely used in Iran and a 2019 study found only 36 percent of doctors were familiar with the concept [20]. In April this year a deputy health minister announced Iran would begin to roll out telemedicine in response to coronavirus [21]; the challenge now will be to roll out this technology at pace, and to try to overcome issues of ICT literacy, patients’ disputable access to video-conferencing technologies, and linguistic and cultural barriers.

For patients with severe Covid-19, rapid access to an adequately-resourced hospital setting is paramount. So is their ability to meet the cost of treatment. Iran currently employs a mandatory insurance-based system backed by the government and by 2014, after President Hassan Rouhani introduced a safety-net scheme for the uninsured – dubbed “Rouhanicare” – close to 100 percent of Iranians are now thought to have some kind of medical cover [22].

Widespread insurance coverage does not mean universal healthcare has been achieved; far from it. [23] In fact, even with close to 100 percent of Iranians insured, out-of-pocket payments – costs borne directly by sick patients and their families at the point of care – are still assessed as having accounted for between 42 [24] and 50 [25] percent of the resources of the entire Iranian health system in 2017. This compares to a global average of 24 percent.

Among the probable contributing factors to this disturbing situation are undocumented informal payments, a non-coverage of private care by the main insurance providers [26] and the often-exorbitant deposits levied by private hospitals before admission, which in turn can have an impact on Iranians’ ability or willingness to present at an acute setting when they fall sick. Insurance payouts to government hospitals have also sometimes been delayed by up to two years, affecting providers’ ability to meet their operating costs – up to and including the payment of hospital utility bills.[27]

Worse still, Iran-based studies continue to record high rates of catastrophic health expenditure (CHE): the never-situation in which patients are likely to have to choose between paying for medical care and other essentials such as heating or clothing, defined by the WHO as when a household is spending upwards of 40 percent of its non-subsistence income on medical costs.

A recent study found that an average of 6.9 percent of Iranian families had experienced CHE between 2011 and 2017: the highest rate in a single period since 1984 [28]. Between 1984 and 2014, another found, levels of CHE exposure stood at 2.3 percent in urban areas and 3.4 percent in rural areas [29]. The urban-rural disparity, its authors suggested, may be because rural insured patients, due to the scarcity of local specialist treatment centers, are sometimes forced to see consultant physicians outside the referral system ordered by a GP.

This incurs private costs for people already more likely to be among the most deprived in Iran. Between 2013 and 2017, the number of households below the poverty line nationwide rose from 8 to 10.9 percent [30], and poverty headcount ratios were much higher in under-developed and rural areas: an average of 27 percent overall, compared to six percent in urban areas. Data show between 75 and 90 percent of the population in some parts of Sistan and Baluchistan were living below the poverty line in 2011 [31]. Political and economic turbulence since then are likely to have exacerbated the situation since these studies were conducted.

Prologue III: Access to Information, Culture and Public Trust

The prior experiences of other countries – and events as they unfolded in 2020 – have shown that during a public health emergency, clear and consistent public health messaging is critical to effective pandemic management, as is a high degree of public trust in officials and official sources of information [32].

In Iran, media output has been censored and controlled as a matter of course both before and since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. State-owned broadcasters such as Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) and PressTV have a mandate to reproduce supra-statist narratives at all times. Their output is reproduced and often embellished by semi-official news outlets affiliated to the ideological and security apparatus, such the Iranian Students’ News Agency (ISNA), Tasnim News and Fars News Agency. The threat of fines, imprisonment and closure compels all publications to rigorously self-censor at the expense of accurate reporting.

Iranians’ access to alternative sources of information is constrained. Foreign television channels and internet platforms such as Facebook, YouTube and Telegram are blocked by the state alongside close to 80 percent of the world’s most-visited news websites, according to Iran International. [33] An increasing number of Iranians are turning to VPNs and circumvention software to get around the firewall, but many more do not have recourse to these methods.

As a result, by December 2020, Dr Esfandiari notes there was “a huge difference between people in large cities and rural areas, and between different groups with different levels of education, in their knowledge of this disease. People in rural areas may not even have access to a smartphone. Their knowledge is less, and this can impact on case numbers.”

The pandemic also occurred in the midst of a long-observed [34] atrophy of public trust in Iranian state officals and official news sources. In late October 2020, an independent survey for IranWire found that although the IRIB is still the most-turned-to news source by most Iranians, around 70 percent of respondents did not completely trust its output and 75 percent did not fully trust the Ministry of Health’s daily Covid-19 briefings. Moreover, some 80 percent of respondents said they did not fully trust the government to resolve the epidemic. [35]

Throughout 2020 the most important coronavirus-related information was conveyed to Iranians by politicians in the state media (as opposed to by doctors, scientists or epidemiologists in a healthy and independent press). Lack of trust in both of these entities may well have had an impact on how far many people took Covid-19 seriously or complied with health guidelines. Indeed, surveys in Tehran municipality found that 37 percent of respondents were “little worried” about coronavirus at the end of May, [36] and up to 10 percent “did not believe in coronavirus” in December. [37]

Socio-cultural factors may also have affected how some Iranians responded to the epidemic. A centuries-old belief in herbal medicine, a hot-button issue between politicians and steadfastly promoted by much of the clerical establishment, still finds adherents across all strata of Iranian society [38]. For more than 10 years the Iranian regime promoted “Islamic medicine” in its propaganda before changing the official name to “traditional medicine” in response to sustained criticism and establishing a Faculty of Traditional Medicine within the Ministry of Health. At the same time, the dearth of human capital in the Iranian clinical research sector and a perceived lack of oversight in domestic drug development has meant that many Iranians, Dr Esfandiari states, “don’t trust medications manufactured in Iran” and out of either preference or desperation self-medicate with herbal or black-market remedies.

The absence of unified, clear guidance from trusted professionals has had far-reaching consequences in Iran during Covid-19, and continues to shape individual and collective responses to the epidemic today. Efforts by individual government officials, citizen journalists and medical practitioners to turn the ontological tide have been strangulated by competing interests at the top level. This is a battle they cannot afford to keep losing

Part One: Winter and the First Wave

Like some other countries that experienced an early outbreak of coronavirus, Iran was slow to recognize the dangers of SARS-CoV-2 and to announce the detection of its first domestic cases. For security, ideological and economic reasons the Iranian authorities first outright denied the outbreak, then delayed the implementation of social distancing measures intended to slow the infection rate.

Amy Dighe, a researcher at Imperial College London’s MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, has examined non-pharmaceutical interventions to Covid-19 outbreaks in Europe and South Korea. “We now know,” she says, “that early, decisive action is really important.

“Some countries immediately tried to suppresss Covid-19 but others didn’t feel that was possible, or felt mitigation to prevent the overwhelming of the health service would be a better approach. How widespread the disease already is can impact on options. But we have learned for now that it’s possible to control coronavirus if you do act very early, and very decisively.”[39]

On January 12, 2020, the World Health Organization had published a statement describing the symptoms associated with the new coronavirus disease. The text was translated on the same day in Iran and sent to all universities, hospitals and medical centers in the country for guidance on recognizing and treating Covid-19.

However, it was not until January 22 that the Iranian government issued its first formal statement on coronavirus to the Iranian public. Hossein Erfani, head of infectious diseases at the Ministry of Health, declared on that day that no case of novel coronavirus had been detected in Iran [40]; the BBC later revealed that in fact, this was the same day the first death from Covid-19 had been logged in medical records at an Iranian hospital [41].

Erfani did go on to confirm that a screening team had been stationed at Imam Khomeini Airport in Tehran to “monitor” travellers entering the country from China. At the time, Iranian airport staff were testing incoming travellers’ body temperatures with laser thermometers. This may have had only a trivial effect in detecting or preventing cross-infection given the still-uncertain proportion of asymptomatic cases, and the often lengthy “incubation period” – the period of time from exposure to onset of symptoms – which is now thought to average around five days but can last for up to 14.

On January 31, a delayed suspension of flights between Iran and China came into effect. This was vehemently resisted by the CEO of Iran’s main commercial airline, Mahan Air, which is close to the IRGC. Several months later it emerged that Mahan had quietly received permission from Iranian authorities to conduct a further 157 flights to and from China and other countries from January 31 to April 20. [42]

Iran did not formally announce its first two cases of Covid-19 to the WHO until February 19; the index case was then said to have been a merchant from Qom who had travelled to China. But since then a group of scholars have analyzed the genomic sequences of 34 air travellers from countries such as Canada, Australia, Pakistan, Austria and Finland, who had spent time in Iran, and surmised that the epidemic may have started in the country from at least as early as January 21, with a then-doubling time of three days.

By further analyzing the air travel data of confirmed exported cases from Iran, these researchers concluded the number of infectious individuals in Iran may have been 18,500 by February 25 – and 259,500 by March 6 [43]. This is more than 100 times the number of confirmed cases being reported by the Iranian Ministry of Health at that time.

The City of Qom: A Case Study

By late January the first inpatients at Kamkar Hospital in Qom, north-central Iran, were being treated for symptoms of Covid-19. Doctors in this city found none of the typical remedies for seasonal influenza were helping these patients to recover. Polyamerase chain reaction (PCR) test kits had not yet been supplied to hospitals and on this pretext, the first deaths from Covid-19 were not declared by the government or by health officials.

Qom is the seventh largest metropolis in Iran and lies around 120km south of the capital, Tehran. In 2020 the city had a population of more than a million and a relatively high population density of 4,500 people per square kilometer: important in the context of Covid-19 because naturally, an infectious disease spreads faster in more developed areas. In 2016 some 38 percent of the urban population of Qom were living below the poverty line. [44] That year, there were also just 144 hospital beds available to every 100,000 people in Qom [45]: below average even for Iran.

Despite the high levels of urban poverty, Qom is of enormous strategic and financial importance to the Iranian supra-state and the Supreme Leader. Together with the city of Mashhad, which also experienced an early outbreak of coronvavirus, Qom is regarded as one of the holiest cities for Shia Muslims as it is home to the shrine of Fatimeh Masumeh, the sister of Imam Reza, and to Jamkaran Mosque.

Qom is also the largest center for Shia scholarship in the world and serves as a base for much of the clerical establishment, including powerful Grand Ayatollahs who derive significant status and income from the up to 20 million pilgrimages made to the city each year. Part of that income is ostensibly spent, through a nexus of religious foundations that operate independently of government, to the benefit of wider society – and rather more demonstrably, to the benefit of the IRGC [46]. For this reason, the outbreak of a fatal infectious disease in Qom was construed as an existential threat by both Iran’s religious establishment and the security agencies.

Early Containment

From mid-January through to late February, the position of the Iranian government and security services was to deny the existence of coronavirus in Iran. Between January 20 and February 18, in at least 29 separate interviews and statements to the media, state representatives and health officials denied reports of a domestic outbreak [47]. For example, on January 28, deputy health minister Iraj Harirchi claimed that by taking “immediate action” the authorities had already stopped SARS-CoV-2 spreading to the country.

These denials came as journalists, medical practitioners and members of the public were raising concerns about possible SARS-CoV-2 infections inside Iran. On January 30, the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) reported two Chinese tourists with symptoms of Covid-19 had been hospitalized in Tabriz, the capital of East Azerbaijan. The next day it was alleged that a guest at a Tehran hotel was also sick with Covid-19, and on February 10, the newspaper Iran claimed a 60-year-old woman had died from Covid-19 in Tehran province [48]. Iranians began to post on social media documenting cases of what they believed to be Covid-19.

The state and security apparatus responded with strenuous efforts to stifle reporting of the outbreak. The Ministry of Health filed complaints against journalists and social media users who wrote about coronavirus, and reporters received threatening calls from Iran’s cyber police and the IRGC for publishing “unauthorized” news about the pandemic, while offending newspapers were confiscated from kiosks in the high-transmission areas of Gilan and Qom.

The first report of a journalist arrested for “rumormongering” was received by IranWire in mid-February [49]. In the weeks that followed, many more individuals – including ordinary citizens, reporters, and even a former city council member and the captain of the national football team – would be arrested on such charges as “disturbing public opinion” and “creating mistrust” over remarks that contradicted the official line on coronavirus [50].

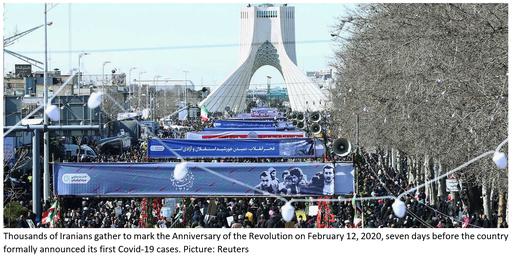

Without clear guidance on the dangers of Covid-19, mandatory celebrations to mark the Anniversary of the Revolution took place on February 12. Thousands of Iranians took to the streets without keeping their distance from one another or taking sanitary precautions.

Six days later, on February 18, Dr Mohammad Molaei, a well-known radiologist at Kamkar Hospital, publicly stated that a test on the body of his brother Hossein – a 60-year-old retired teacher who had first shown Covid-19 symptoms on February 4, and died in hospital on February 16 – had returned a positive result. A TV news program linked to the IRGC attempted to smear Dr Molaei by claiming he had fabricated evidence of his brother’s sickness. But finally, the Iranian government was forced to declare its first two cases and deaths from Covid-19 to the WHO on February 19. A National Coronavirus Combat Taskforce, chaired by President Rouhani, was formed with a mandate to manage the domestic epidemic.

The guidance the government gave the public on February 19 was to limit the size of gatherings and take additional sanitary precautions such as hand-washing: measures which, taken in isolation, are likely to have a negligible effect on transmission rates. But even this guidance was specifically not to take effect until February 22: the day after parliamentary elections were scheduled to take place across Iran. This was on the instructions of the Civil Defense Organization, which according to leaked correspondence, may have been aware of Covid-19 infections in Qom since as early as January 31 [51].

On February 19, deputy health minister Ghasem Jan-Babaei also claimed that there were “no cases at all” outside of Qom. And while the government did close schools and universities in Qom and Tehran from Thursday, February 20, it did not quarantine the city for political and economic reasons. Weeks later it emerged that Hossein Taeb, head of the IRGC’s intelligence organization, had described Qom as "the honor of Islam" at a meeting of the Supreme National Security Council, and argued that isolating the holy capital would play into the hands of Iran’s supposed sworn enemy, the United States [52].

Targeted Interventions: A Missed Opportunity?

The response of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the outbreak in Qom stands in contrast to that of the government of South Korea, which reported its first case of novel coronavirus on January 20. The state quickly applied targeted interventions after an outbreak was identified in the inland Korean metropolis of Daegu a month later. Such interventions in high-incidence areas allowed South Korea to quickly limit coronavirus transmission within its borders without the need for sustained, country-wide disruption. [53]

“The initial cluster was detected in the Shincheonji religious group,” Amy Dighe says. “The government introduced a quarantine for two weeks. It was a very short period compared to lockdowns in some other countries, but it was implemented as soon as the cluster of local transmission was detected, and it was very strong. And the explosive case growth seen in that region led to people reacting by reducing their movement nationwide.”

The South Korean government and the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCD) also embarked on the early mass-production of diagnostic tests in partnership with private firms inside the country, instead of relying on test kits imported from abroad. Officials actively sought out members of communities known to have been affected by Covid-19 and encouraged them to take a test.

Dr Lee Whanhee, a research associate of the Graduate School of Public Health at Seoul National University, is one of a group of scholars who identified that in this instance, each introduction of 1000 diagnostic tests was associated with a decrease of 14.5 new confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 [54].

“Based on the mass production,” he says, “the KCDC could perform full-case inspections for mass-infection groups and areas such as nursing homes, and could quarantine people immediately. Aggressive testing reduced the likelihood of contact with confirmed cases and ultimately decreased transmission.”

These localised measures saw South Korea bring newly-reported infections down to single digits by early April. Daily case numbers also stayed comparatively low throughout the summer, with similar tactics deployed to contain sporadic surges emanating from the Seoul metropolitan area. Like many countries, South Korea has begun to record high numbers of new infections since mid-November, but even now daily confirmed new cases have only once surpassed 1,200 in a country of 51.6 million. This suggests targeted interventions have proved efficient and, moreover, cost-effective for a country that like Iran, is highly reliant on overseas trade and could not necessarily afford a protracted lockdown.

“As far as I know,” Dr Whanhee says, “the Korean government and KCDC did not only take into account a decrease in the spread of infection in their policies. If they had focused only on this, a nationwide lockdown could have been an effective option. But a lockdown policy can generate big after-effects, especially in the economic field. I think the Korean approach was quite effective in defending [against] economic crisis as well as epidemic.”

Notably, Dr Whanhee and colleagues also found that fewer medical resources in some regions of South Korea – such as ICUs and ventilators – were associated with a higher Covid-19 case fatality ratio in those areas. This is a correlation that can tentatively be observed in Iran.

Dr Whanhee is also emphatic that clear, consistent public health messaging played a key role in the early success in South Korea. This country had the benefit of hindsight due to experiencing infectious disease outbreaks before Covid-19. “During MERS [the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak of 2015],” Dr Whanhee says, “the (former) government did not share information about patterns of infections or the hospitals people were in. People were terrified, and endless fake information was disseminated online, heightening this fear.

“More seriously there were cases in which severe non-MERS patients became infected after going to the emergency room without being aware of the hospitalization of MERS patients there. So after MERS, the government and KCDC determined that open and transparent communication is much more effective in encouraging people to take the precautions that can reduce transmission.”

Endemic Confusion

In Iran, the failure to quarantine Qom led to the virus spreading rapidly in the local population and to other provinces. A lack of information about the risks of transmission meant school closures in Qom and Tehran prompted a surge in holiday traffic to the northern provinces of Mazandaran and Gilan; identified cases in these areas increased rapidly, and with no restrictions on inter-city travel, the infection soon spread throughout the rest of the country.

Despite mounting evidence to the contrary emanating from emergency wards, senior government and security officials in Iran downplayed the severity of the epidemic even after acknowledging the first cases. Some falsely claimed coronavirus was “under control” [55] and others, that the curve of infections in Qom was going down [56]. Deputy health minister Iraj Harirchi also claimed Iranians could take the same precautions against coronavirus as they might ordinarily take against seasonal flu. Apart from being wrong, this was unlikely to inspire confidence in a population that had seen a 20 percent increase in positive flu cases in fall 2019 with the co-circulation of both flu types A and B in Iran, leading to many deaths amid a shortage of flu vaccines that the government had blamed on sanctions [57].

With no clear understanding of the risks, almost 24 million Iranians went to the polls during the parliamentary elections on February 21. Footage broadcast from polling stations showed people standing in packed queues, with nominal enforcement of physical distancing or hand hygiene, and fingerprint validation still used despite this no longer being mandatory.

Even after the elections were over, the city of Qom was still not quarantined and no travel restrictions were imposed due to (misguided) economic concerns and strong push-back from members of the religious establishment, on whom the Supreme Leader relies for support [58]. On February 26, the city’s Friday Imam and the guardian of the Fatima Masoumeh Shrine, Mohammad Saeedi, claimed that in fact the shrine was “a house of healing” and “people must come here in force”. Guardians of the shrine rubbished the idea of suspending Friday prayers or disinfecting religious sites, and the Qom-based cleric Ayatollah Hossein Vahid Khorasani instead advised seminary students to pray to ward off Covid-19.

Some weeks later, a seminary student from Najaf, Iraq would tell IranWire that many members of the clergy had in fact wanted to see the city quarantined but “remained silent out of fear”. “We were told,” he said, “that we wanted to put the regime in peril and coronavirus was a Western conspiracy. It is like we are living in the Middle Ages.” [59]

These concerns in turn also slowed decisive action by the National Coronavirus Taskforce and the Ministry of Health. In an address to his cabinet on February 25, President Hassan Rouhani insisted again that Qom would not be quarantined, and that coronavirus “must not become a weapon in the hands of the enemy to shut down the country”.

This pronouncement came on the same day that a deputy health minister, Iraj Harirchi, spectacularly declared he had tested positive for Covid-19 shortly after giving an ill-fated press conference in which, while coughing and sweating profusely, he had dismissed quarantine as belonging “to the pre-World War One era”. Harirchi was one of dozens of senior Iranian officials to become infected with coronavirus that week alone, including Iran’s first vice president Eshagh Jahangiri, no fewer than 23 members of parliament, and the president of Qom University of Medical Sciences.

The state and security forces continued to suppress reporting of the outbreak. Ultimately on March 11 the Iranian prosecutor-general, Mohammad Jafar Montazeri, would issue a statement confirming that “any comment [about coronavirus] outside the routine is considered an act contrary to the national security of the country.” [60]

The impulsive securitization of the epidemic also extended to silencing members of the medical profession. On Saturday, February 22, a group of Tehran-based specialists attended a meeting with Health Ministry representatives in which they reported their findings about coronavirus in several Iranian cities. After the meeting, they were contacted by the IRGC through the health ministry’s security department to warn them there would be “consequences” if any part of the discussion were made public. “The statistics published by the government have nothing to do with reality,” one of the doctors told IranWire. “If things go on like this and the Islamic Republic does not cooperate with the WHO, we must expect disaster.” [61]

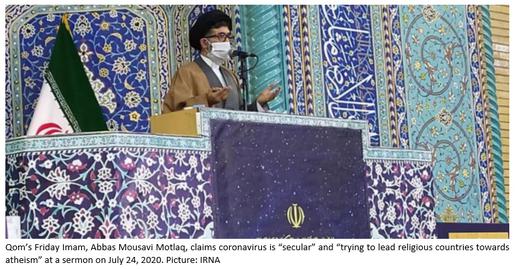

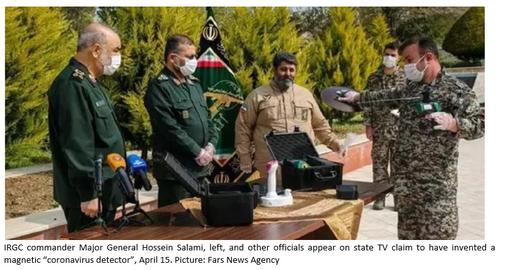

During this period and throughout the rest of 2020 Iran’s state-controlled media was also marshalled by a constellation of third parties – most notably the IRGC – to misrepresent the threat posed by coronavirus and promote disinformation about the origin and nature of the virus, to suit their own purposes. The oblique aim of most of these publications was to position SARS-CoV-2 as a security threat instead of a public health emergency. To an extent probably unmatched anywhere outside the Kremlin, the state-controlled IRIB, PressTV, Tasnim News Agency and others gave hours of airtime to “experts” promoting antisemitic, anti-West and anti-US conspiracy theories, which have long been used as a discursive tool by the Islamic Republic, now framed instead by the pandemic.

By means of a non-exhaustive list, state-controlled media, the Supreme Leader and IRGC-affiliated bodies have variously proclaimed SARS-CoV-2 might be a ruse cooked up by “enemies” to deter Iranians from voting in the elections; a “biological ethnic weapon” created by “Americans and [the] Zionist regime”; a population control project to establish the New World Order; or an ethnic-biological attack on Iranians using covertly-harvested genetic data. PressTV went so far as to suggest that coronavirus was not real but a politically-motivated hoax comparable to “the Zionist/Neocon false flag events of 9/11/2001”.

These publications often mixed quotations from fictitious sources, such as the “Israeli Academy for Studying Domestic Security”, with ordinary reporting and packaged the fantasies therein as reliable news stories. The Supreme Leader also explicitly repeated the “bio-weapon” conspiracy theory in his instructions to the Civil Defense Organization for dealing with coronavirus, and again in his Iranian New Year (Nowruz) address to the nation [62].

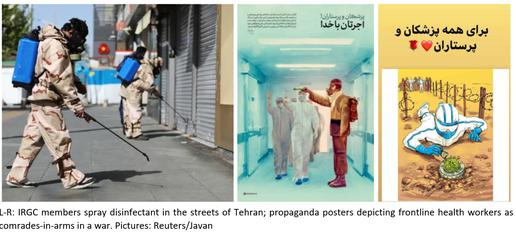

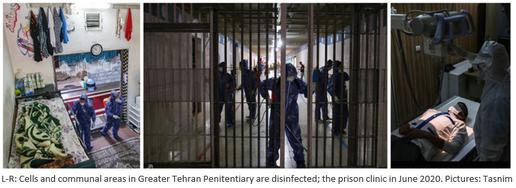

The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps simultaneously used security services-aligned media channels, chiefly Tasnim News Agency and the hardline newspaper Javan, to portray the battle against coronavirus as an Islamist crusade. The IRGC’s crack teams dispatched to disinfect the streets of Gilan were depicted as “defenders of health”, and those who died from Covid-19 were glorified online as “martyrs” [63]. The IRGC even adapted old wartime posters from the Iran-Iraq War to display its fighters side-by-side with medical professionals. “Only the trenches have changed,” one proclaimed [64].

The so-called trench of 2020 was in fact comparable only to those of the 1980-1988 war in its unpreparedness for the extent of the crisis Iran was now facing. By February 24, Kamkar Hospital reported it was at full capacity while doctors sounded the alarm over equipment shortages. “The medical team is helpless,” one source told IranWire. “They lack specialist equipment and supplies and have not received training to protect themselves. A number of doctors and nurses have been infected before our eyes and put to bed in the hospital.” [65]

That same day, four specialist doctors abandoned their posts in that hospital in fear for their lives. Operators at Tehran Emergency Center, meanwhile, reported a stream of suspected Covid-19 sufferers and a chronic lack of personal protective equipment. “We ran out of goggles on Sunday morning,” one Tehran-based medical worker told IranWire. “They sent us goggles for welders… [and said] ‘Don’t worry, just wear masks and gloves’. The hospital’s dispensary is out of paper surgical masks.”

Several medical personnel were reported to be seriously ill with Covid-19 in Gilan province, and on February 24 Dr Reza Koochekinia, the president of the health network in the city of Astaneh, was reported to have died from Covid-19 in Pars Hospital [66]. He is now among thousands of health workers thought to have lost their lives to Covid-19 in Iran.

With the gulf between public statements and reality no longer tenable, the government began to introduce non-pharmaceutical interventions throughout Iran in a piecemeal fashion. Schools were closed across the rest of the country on February 28, and reductions in working hours at banks and government offices were announced on March 7. Religious shrines were belatedly closed on March 14, while people were advised against large gatherings and to limit their travel, though not forbidden from either. Businesses were advised to close, but not formally ordered to do so until March 20: the date of Nowruz, Iranian New Year.

That week, with restrictions not enshrined in Iranian law and in a mixed atmosphere of fear, frivolity and confusion, millions of Iranians travelled across the country to gather with their families for the holidays. It was not until a full week after Nowruz that an outright ban on inter-city travel and gatherings came into effect, together with the closure of parks, pools and recreation venues: the closest Iran came to a “lockdown” in the early part of the year.

The Problem with Numbers

The Iranian Ministry of Health is widely understood to have significantly underreported new coronavirus infections and deaths to the WHO and to the Iranian public. Part of this is for logistical reasons: initially, shortages of PCR tests meant only hospitalized patients with severe symptoms received a test, and even after domestic test production improved in the spring, anecdotal reports and leaked official material [67] indicate only a fraction of the infected population has been included in the official daily “case count”.

Many people infected with SARS-CoV-2 experienced either no symptoms or symptoms mild enough to recover at home, meaning they were not tested. Some Iranian firms have now capitalized on the virus by offering “instant-result” testing services at parties and private functions, but the results of these are not shared with government and in any case, would be highly questionable [68]. Even among those that do receive a test, the propensity of PCR swab tests (both overall and Iranian-manufactured) to return a false-positive or false-negative result depending on the quality and the speed of processing is still uncertain.

In line with WHO guidance, from the beginning Iranian doctors could also clinically diagnose Covid-19 through other methods such as a CT scan of the lungs. But in Iran advanced imaging technologies are also in short supply, with a reported 6.93 CT scanners per 1 million population in 2016 and CT scanners found to be unevenly distributed in different areas. [69]

In February, the head of Gilan University of Medical Sciences claimed that just one working CT scanner was available at Poursina Hospital for the 640,000 people living in the provincial capital of Rasht. [70] This means that even among those Iranians with Covid-19 who did go to hospital, there is every likelihood that not all were diagnosed correctly.

There were also signs in the summer that the Ministry of Health had knowingly separated the data of Covid-19 patients clinically diagnosed via CT scans from that of those who returned a positive PCR test [71]. And in March, newly-bereaved families began to tell IranWire that they had been warned by security agencies not to tell anyone that their loved ones had died from Covid-19 or they would not receive the body for burial. [72]

Many people who died with Covid-19 symptoms have had “stoppage of the heart”, “respiratory disorder” or “severe pulmonary syndrome” cited as the cause of death on their death certificates on the orders of chief justice Ebrahim Raeesi. [73] It meant these deaths did not have to be included in the figures reported by the Ministry of Health to the WHO (or broadcast by the IRIB to the people).

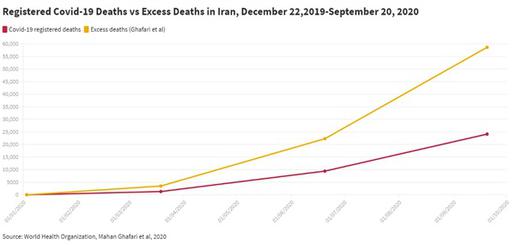

This, as well as massive discrepancies between the figures announced by medical schools and provincial authorities on the one hand, and the Ministry of Health on the other, all suggests that deliberately under-estimated national figures were and are being reported to the WHO. In October last year deputy health minister Iraj Harirchi finally admitted that in his view, at least 50 percent of deaths from Covid-19 in Iran had gone unreported [74].

In late February 2020, these discrepancies prompted the Ministry of Health to order provincial authorities to stop announcing their own figures, with varying degrees of success. Then in March, a blanket ban was imposed on reporting statistics and information not endorsed by the ministry . Even though many Universities of Medical Sciences and local politicians have not taken the ban seriously, it has meant that for most of the year, the 75 percent of Iranians who rely chiefly on the IRIB for their news have received a deformed picture of nationwide infections and deaths, and no up-to-date official figures at all on the epedemiological situation close to where they live.

Making Up for the Shortfall

Early efforts have been made by scholars both inside and outside Iran to try to gauge the true impact of the epidemic in the country. Barely a year has passed since the emergence of a new disease and with no pre-existing data from which to draw inferences, any and all conclusions remain tentative at best.

Some studies, however, stand out and are worth mentioning in the context of how events are thought to have unfolded in Iran. In summer 2020 a cross-disciplinary group of researchers from Iran, Australia, Europe and the US attempted to estimate what the true nationwide infection rate might have been during discrete time periods in the early weeks of the outbreak.

Based on the official figures reported to the WHO, Iran had recorded an improbably high case fatality ratio (CFR) of 16.8 percent by February 25. This extreme number, the researchers surmised, “could correspond to a significant level of underreporting of the infected cases and an overwhelmed health system.” [75]

Instead, they developed a mathematical model to estimate changes in the effective reproduction number – known as the R(t), or the average number of new people infected by an infectious person, during their infectious period, at a given point of the epidemic – based on several assumptions. The team assumed the following: that – in line with early estimates around the world at the time – Iran was experiencing a “true” base CFR of 1.4 percent; that Iranians with coronavirus had a mean 5.5-day incubation period; and that patients had an average of 22.2 days from the onset of symptoms to either recovery or death. An R(t) of above 1 indicates the disease is spreading; an R(t) below 1 indicates the epidemic is shrinking.

Based on this circumspect formula, researchers estimate the R(t) across Iran would have stood at around 1.73 on March 1, 2020. By March 8 this would have dropped down to 1.35, which could be consistent with increased public awareness of the crisis and social distancing policies in place by that time. Their estimated R(t) then decreased consistently to 1.04 on March 20, but shot back up to 1.52 on March 30: just over a week after millions of Iranians had travelled around the country and attended family gatherings for Nowruz.

These cautious estimates are based on the nationwide figures. It is not possible to repeat the exercise at the level of individual provinces because the Ministry of Health has not published province-level data. The province-level figures relayed in public statements by local hospital CEOs collected by IranWire in 2020 vary over time in both their content and frequency [76].

Instead, another group of scholars, whose research has not yet been peer-reviewed, has attempted to map the rough geographical spread and impact of Covid-19 in Iran through a study of the number of deaths registered in Iranian provinces in winter 2019/20, spring 2020 and summer 2020, as published by Iran’s National Organization for Civil Registration [77]. They calculated the expected number of deaths, per province and for each season, based on previous records, before using this to gauge how many “excess” or unexpected deaths were recorded in the relevant periods. A significant deviation from what was expected could, it was reasoned, be attributed to Covid-19.

If map fails to load, refresh your browser or click here

No definite judgements about the number of Covid-19 deaths in Iran can be made based on these figures alone. Death rates reported by the Civil Registration Organization have fluctuated in the past and other factors could have a bearing on an apparent increase in recorded deaths in a given place. But where the increases are significant, they may nonetheless offer some suggestion as to where and how badly the epidemic may have affected local communities in Iran.

Lead researcher Mahan Ghafari, a doctoral researcher studying virus evolution at Oxford University’s Department of Zoology, says: “Not every excess death will be directly related to infections from Covid, and although Iran generally reports up to 90 percent of its annual all-cause mortality data, their coverage could have been impacted during the Covid epidemic across the country. We also have to realise that a lot of countries release their numbers of registered deaths every week, but Iran does it every three months, which makes it challenging to analyse the data and make sense of it.

“Registered deaths per province or per city, and how well-equipped different hospitals are to deal with Covid patients, which is a factor in an area having more deaths, are terribly under-studied in Iran. This is the only data we have at the moment to gauge the level of spread at the province level. Without understanding the geographical spread of the disease, you are fighting blind.”

But even in this early period, the results of the study do seem to align with what is broadly known about the early “epicentre” of Covid-19 in Iran and the direction of its spread. Many provinces actually recorded fewer deaths than expected over the winter, but from December 22, 2019 to March 19, 2020, four provinces in central and northern Iran – Qom, Gilan, Golestan and Mazandaran – recorded a 27 percent higher mortality rate than researchers would have expected, or an estimated total of 3,476 deaths.

In Qom alone, researchers think 45 percent more deaths than expected – a total of 723 –were registered in the space of three months. Smaller increases in two other provinces known to have been badly-affected by coronavirus by March – including Qazvin, with 5 percent or 85 more deaths than expected, and Tehran, with 3 percent or 467 more – were also observed in the same period. On the eve of Iranian New Year on March 19, 2020, the Iranian Ministry of Health had formally reported 1,284 deaths from coronavirus across the whole of the country.

Part Two: Spring-Summer and the Second Wave

As businesses across Iran were shuttered and families adjusted to spending more time indoors, the Ministry of Health reported record numbers of new daily infections in the days following Nowruz. Some government hospitals reported facing significant challenges in service delivery due to a lack of equipment and bed capacity. “We have to release many patients who still need medical services because we need the beds,” a doctor in Sanandaj, Kurdistan told IranWire.

In all likelihood to avoid the expensive deposits charged by private hospitals, Covid-19 patients were directed to designated government-run treatment centers, which mitigated the danger of cross-infection but also meant some provinces did not have the facilities they needed to handle this level of patient inflow. “In the city of Babol [in Mazandaran province]”, Dr Esfandiari says, “there are three hospitals that are dependent on the government. Of these, only one actually had the facilities to admit Covid-19 patients.”

Staff at designated facilities also complained of chronic shortages of PPE and unsafe working conditions at a time when global demand for PPE was far outstripping supply. By March 4, at least 11 medical personnel in Gilan had lost their lives to suspected Covid-19, with one nurse describing Razi Hospital in Rasht, where the IRGC was already setting up a 100-bed field hospital in the grounds to deal with the unprecedented number of new admissions, as a “slaughterhouse” [78]. “We have no masks, no protective gear and no equipment,” she said.

Another nurse at a private hospital in Rasht said staff were using the same, unchanged protective gear over multiple shifts, while still another at Pirouz Hospital in the city of Lahijan, Gilan said staff had “no equipment whatsoever” and members of the public had been donating masks to medical teams in Lahijan and Langarud. “Every day six to eight people die before my eyes,” she said.

On March 8, IranWire learned that in late February one Dr Omid Rahnama, an anesthesiologist at Ghaem International Hospital in Rasht, had written a note addressed to the hospital’s president shortly before he lost consciousness and was connected to a respirator. “If something happens to me,” Dr Rahnama wrote, “I will not forget those who did not provide protective gear to myself and my colleagues. Last Wednesday in the ICU, from morning until noon, I was begging for a mask. I will not forgive those who told staff, who were working while feeling sick and suffering from fever, ‘You cannot have medical leave’.” [79]

Mohammad Hossein Ghorbani, plenipotentiary representative of the Health Minister in Gilan, said on March 8 that he believed 200 people in the province had lost their lives to the epidemic. The news was suppressed and a few hours later, Fars News Agency published an interview with Ghorbani, who now said that he had been misunderstood. What he meant, he said, was that in the past 16 days, 200 hundred people had died of “respiratory illnesses”.

The ill-equippedness of government hospitals to deal with the pandemic was thrown into sharp relief – and immediately politicized – on March 12. Blaming sanctions for the shortages, minister Javad Zarif tweeted a list of supplies he said the Health Ministry would need to fight Covid-19, which included 160 million three-layer masks, 12 million N95 masks, 100 million gloves, 1,000 ventilators, 3.2 million test kits and 25,000 pulse oximeters as well as millions of doses of four drugs being used in Iranian hospitals to treat Covid-19 symptoms [80].

IranWire was also informed by multiple sources that two drugs, hydroxychloroquine and oseltamivir, were in short supply in hospitals due to historic and recent stockpiling [81]. An official working with the National Coronavirus Taskforce, who had just been informed that imposing martial law in high-transmission areas would not be possible, told IranWire: “The world must know about the severe shortage of these two drugs, to force the regime to declare an emergency situation and ask the outside world for help.” [82] Hydroxychloroquine was later shown to be ineffective at reducing death from Covid-19.

How far the cost of treatment has had an impact on Iranian Covid-19 patients’ ability to access adequate medical care is still an unknown quantity. On April 5, Iranian news media claimed the Ministry of Health had written to the Universities of Medical Sciences telling them to recoup the cost of Covid-19 treatment from health insurance, and to absorb the costs of uninsured patients into their transformation budgets.

But two days later, the president of Qom University of Medical Sciences said hospitals had received no such order. Whatever the truth of the matter, the Ministry of Health finally decided patients would bear 10 percent of the cost of treatment in government hospitals. In September, according to the president of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, the average cost of a Covid-19-related hospital stay in his province was 20 million tomans ($714) [83]: an unthinkable amount of money for many Iranians.

In July the government began to relax restrictions on private hospitals admitting Covid-19 patients. Reports quickly surfaced in Iranian media of desperate Iranians taking out loans to pay for their family members to receive treatment at private hospitals.

Too Much, Too Soon

Researchers who conducted the nationwide data modelling exercise mentioned in the previous chapter believe that the first “peak” in coronavirus infections across Iran may have taken place on or around April 5. The proportion of daily new infections announced by the Health Ministry then began to decrease.

This group surmises that based on their assumptions, the R(t) across Iran would have dropped to 1.0 by April 9, and then to 0.69 by April 15: meaning the epidemic may have been receding, but that coronavirus had not been eradicated from Iran. [84]

Experiences from around the world now show the early relaxation of restrictions can have serious consequences. One case study is Nigeria: a country that, like Iran, had scant resources with which to deal with the epidemic including poor access to diagnostic tests, a paucity of specialist staff and under-equipped hospital facilities [85].

The country scrambled to distribute the resources that it already had at its disposal due to past outbreaks of infectious diseases such as Ebola and yellow fever, and issued shelter-in-place orders in late March. But the early relaxation of lockdowns in successive states led to newly-recorded cases rapidly increasing, and in that time, senior health officials also observed diminishing levels of public compliance with sanitary guidelines.

Professor Abdulsalam Nasidi, the former director-general of the Nigeria Center for Disease Control, served as Nigeria’s chief epidemiologist for 16 years and spearheaded the country’s Ebola response. When the first imported Covid-19 cases were detected, he says, “We used some of the key units on the ground that we had used for Ebola, and co-ordinated emergency operating centers that worked with the government and frontline organisations. [86]

“The government imposed a total lockdownfor two weeks, extended to almost six. Nobody opposed the response that was devised and because we had already had diseases like malaria and typhoid, people were used to this. The federal government also released a huge amount of money to each state to expand bed capacity.”

But after these measures were relaxed in May, replaced instead with a night-time curfew, the country recorded a surge in positive Covid-19 cases among those tested. The initial lockdown had also had adverse effects on households and businesses in Nigeria, and economic concerns delayed the implementation of a second lockdown in winter 2020. [87]

Professor Nasidi said many Nigerians are also now longer taking sanitary precautions. He believes many people stopped believing in the threat posed by Covid-19 because of the low national figures being reported – due, in turn, to low testing capacity. “In the beginning,” he says, “the level of public trust was fantastic; people absorbed the messages. But unfortunately that has collapsed. People saw that compared to Europe and America there were fewer cases, so compliance wore off.”

In Iran, the restrictions similarly appear to have been relaxed too soon. Fewer than 10 days after the last nationwide restrictions were implemented, the government announced a shift to a policy it termed “smart social distancing” in which “low-risk” businesses could reopen from April 11 in most of the country, and from April 18 in the capital.

The decision was mainly driven by the unprecedented strain placed on an already-weakened economy by the pandemic. Between March 13 and April 28 alone, 783,000 Iranians had newly registered for unemployment insurance, while the governor of Iran’s Central Bank said that due to sanctions and the global Covid-induced plunge in oil prices, the bank could not afford to support more than 23 million Iranian households eligible for subsidies with anything other than credit lines at 12 percent interest.

At a meeting in March 2020, the cabinet had approved the allocation of financial support packages of 200,000 to 600,000 tomans a month (between US$14 and $40), for four months, to the three million Iranians at the most dire risk of food poverty. But at that time, as IranWire’s calculations showed, this would not have been enough to cover the cost of two meals of bread and cheese a day for a family of four [88].

A survey by Tehran Municipality found that in the first week of April, 34 percent of respondents in the capital already could not afford to pay their living expenses, while 35 percent said they could last for no longer than two months [89]. Millions of still-employed Iranians had been forced to continue travelling to and from work during the first “lockdown”, with around 400,000 people still using the Tehran Metro every day in early April.

With all this in mind, factories and warehouses were reopened in Iran from April 11, and shopping centers and bazaars resumed trading from April 20. Near-usual levels of activity recommenced in some high-transmission areas, with traffic and public transport use in Tehran surging back to 75 percent of the norm by April 24.

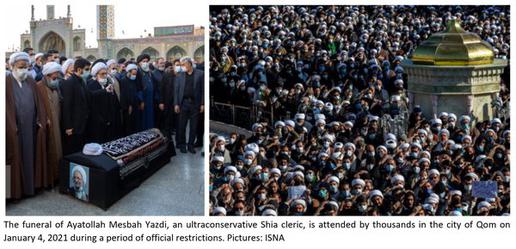

The Muslim holy month of Ramadan then began on April 23. In normal years, increased footfall to mosques and holy shrines is accompanied by increased donations. Pressure to reopen these sites in time was heaped on the government by powerful clerics such Iran’s director of seminaries, the Friday Imams, and media under the control of the Supreme Leader such as the Islamic Propaganda Organization and the ultraconservative newspaper Kayhan [90].

Mosques were ultimately allowed to open their doors to thousands of worshippers for three nights, including the holiest night for Shia Muslims, Laylat ul-Qadr, in mid-May. Muslim places of worship then reopened by degrees from the end of the month onward. Strict guidance against Ramadan rituals, parties and iftar gatherings was issued but the extent to which this was actually enforced is not clear.

Guest houses and inns in “low-transmission” areas were ordered to be ready to receive travellers for Eid al-Fitr on May 24. Restaurants, coffee houses and cinemas were also allowed to resume trading. This aggressive drive toward socio-economic revival came even as Iran’s official Covid-19 figures showed increased numbers of new Covid-19 cases across the country.

Dust Storms

Within weeks of the relaxation of measures, a long-view of anecdotal reports by local officials suggest that certain provinces were experiencing a more significant surge in SARS-CoV-2 infections. One of these was Khuzestan, a comparatively deprived province situated on the Iran-Iraq border. Despite high rates of urban and rural poverty, with all that implies for both access to healthcare and health outcomes, Khuzestan is an industrial hub and home to some 80 percent of Iran’s oil reserves. It is also known for its ethno-cultural diversity, home to relatively large populations of Arabs and Kurds as well as Sunni Muslims and Mandaeans: minorities the Iranian regime has long demonized and disregarded, in discourse and in law.

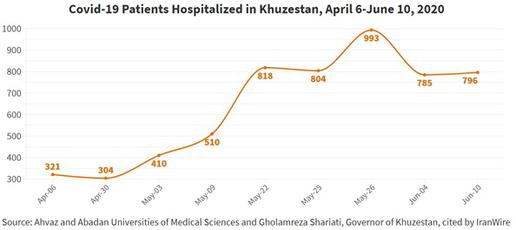

Perhaps with half an eye on the would-be economic consequences of social distancing measures in Khuzestan, and potentially also with a greater degree of flippancy than might have been exhibited in, say, Tehran, on May 6 deputy health minister Ghasem Jan-Babaei claimed that despite a 20 percent increase in infections “in the last few days”, most people in the Khuzestani cities of Ahvaz, Dezful and Abadan were “not seriously ill”.

Within hours the claim was disputed by both Khuzestani doctors and members of the public. The president of Razi Hospital in Ahvaz said one in two people attending hospital were sick enough to be admitted, with many also suffering from diabetes and comorbidities that made them more vulnerable to severe Covid-19. The hospital’s capacity to admit new patients, he said, was already “exhausted” and no ICU beds were available. The same situation was reported at Taleghani Hospital, also in Ahvaz.

That same day, a dust storm was moving in from Iraq. The level of haze in the port city of Abadan reached 6,547 micrograms per cubic meter on the afternoon of May 6, 43.64 times the officially-determined safe level and putting those with respiratory conditions at risk. Despite this, a resident told IranWire: “Everybody is out on the streets. When I say everybody, I mean workers, grocers, children, government employees – everybody. They laugh at those of us who stay home. People do not trust the news and do not take what the government says seriously.” [91]

The Coronavirus Taskforce rubber-stamped the reimposition of some tokenistic restrictions –the closure of offices and banks – in some, but not all, counties of Khuzestan on May 11. But it allowed inter-province travel to continue, and with it the spread of coronavirus.

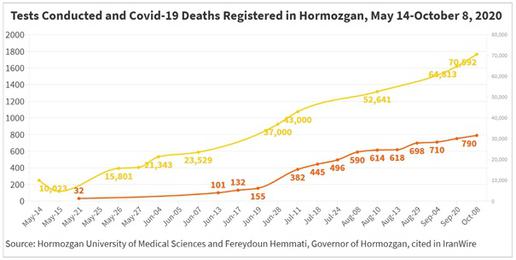

An overview of reports in Iranian media suggests that during this period, particularly worrying situations were developing in poorer, more remote areas such as Kurdistan, Hormozgan, and Sistan and Baluchistan, where some restrictions had also been reimposed. Then on June 1, Health Minister Saeed Namaki made the startling claim that over the course of the previous day, 50 percent of all coronavirus fatalities in Iran had taken place in Sistan and Baluchistan, Kermanshah and Hormozgan [92].

This remark referred to a day when Iran had reported just 63 just new deaths from Covid-19 to its people and to the WHO. It stands as a clear testament to the impossibility of Iran’s official coronavirus statistics given that on June 13, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences alone had said 101 deaths from Covid-19 had been recorded at its teaching hospitals.

In turn the Covid-19 cases and deaths reported in Hormozgan, as detailed above, are likely to have fallen far short of the real figure because of a dearth of testing. On June 14, a group of MPs wrote to President Hassan Rouhani to express their alarm that in Hormozgan, which has a population of nearly two million – and which encompasses some of the most deprived villages and cities in the country, but is also a prominent industrial and agricultural zone and home to the major port of Bandar Abbas – and where some major cities lie more than 500km away from the capital, only one laboratory had apparently been established to process coronavirus PCR tests. Castigating legislative “inattention” to a province “whose voices of deprivation and oppression are less heard by the people of the center”, these MPs stated: “One of the most important factors in the catastrophic coronavirus situation in Hormozgan province has been the lack of adequate facilities.”

Whitewashing

Throughout the course of 2020 Iran’s Ministry of Health used a nebulous series of color-coded alert classifications – “red”, “orange”, “yellow“ and “white” [93] – to describe the level of Covid-19 transmission in a given city or province, at a given time. A location is coded red, the highest alert level, if more than 10 people per 100,000 test positive on a single day.

Based on a city or province’s alert rating, provincial authorities can petition the National Coronavirus Taskforce or the Ministries of Health and Interior – the exact party in which authority is vested appears to have varied on a case-by-case basis – for permission to implement localized restrictions such as travel bans, curfews or business closures.

Putting aside the obvious flaws of this system in a country where testing facilities are both insufficient and unevenly distributed, these ratings offered a distorted representation of infection rates because of the time-lag between a patient becoming infected, (possibly) developing symptoms, (possibly) seeking a Covid-19 test and (if successful) the return of a (fallible) result. Because the formula is flawed, the results are no basis on which to formulate health policy.

Whether the “traffic light” ratings have had any practical bearing on policymaking in Iran is disputable. But at the very least, this broken barometer has been used, time and again, a as a public justification for decisions taken by senior officials. In the first recorded instance of the “traffic lights” being invoked in political discourse, on February 4, 2020, General Gholamreza Jalali, commander of Iran’s Civil Defense Organization, meaninglessly said that Iran’s Covid-19 situation was “white” and no cases of Covid-19 had been detected [94].

This general – who had also heavily promoted “coronavirus-as-biological-attack” conspiracy theory in the early days of the pandemic [95] – then backtracked on national television on February 24, clarifying: “We declared the situation is white so that the global propaganda does not cause psychological harm to the people.” [96]