A note to readers: This article contains graphic descriptions of domestic violence. It also includes a call to action. Please see the final lines for details. You can find the Turkish version of the story here.

Parisa Rajabi is a refugee who fled domestic violence in Iran and has been based in Turkey with her child for the last seven years. Now, the Turkish government has rejected her asylum application and ordered her deportation.

Iranian law does not treat domestic violence as a crime. Moreover, it gives the custody of any children to the father, no matter how brutal or unstable he is. It also gives perpetrators of honor killings a relatively free hand.

Parisa was a schoolteacher in Iran for 16 years, and for six years she also taught at Azad University of Applied Science and Technology and the Payam-e Noor University of Ahvaz. She was born in Ahvaz, the capital of Khuzestan province, and lived what she described as a “tribal life” there.

Tribal communities in Iran are also patriarchal in nature. Membership can compel a woman to obey life-changing decisions, taken on her behalf by others, that work against her own interests. That was what happened to Parisa; after multiple forced marriages she ended up with a violent spouse.

In 2000, while at university, she came to know a man studying for a master’s degree. Her father opposed their marriage because the man was a Persian while she is an ethnic Arab. Parisa told IanWire that he, too, beat her and made threats against her life before making her wed someone she had never met.

Parisa’s first marriage lasted barely two months. That man was a drug addict and ended up being arrested. Parisa’s male relatives agreed to a divorce, but the tribe could not tolerate her “divorcée” status and forced her to marry again.

“My cousin wanted to marry a girl from another tribe,” she explained to IranWire, “so they forced me to marry that girl’s brother. We lived together for two years. My cousin and her wife couldn’t have children, and their quarrels escalated. One day, without telling me anything, my uncles came to our house and took me away, and we were divorced again a few months later. I’d been trying to escape with my husband and didn’t want to get a divorce, but nobody agreed with me or backed me up.”

In some tribal groups, women are treated as bargaining chips in disputes or deals. After Parisa’s second divorce, a bazaar merchant told the chief of her tribe that he had dreamed of one day marrying a sadat girl: a descendant of Prophet Mohammad. “The chief picked me,” Parisa said. “It took just three hours; they told me to go to the marriage bureau in the morning. Needless to say, my opposition, my insistence and my tears had no effect whatsoever.”

The Violence

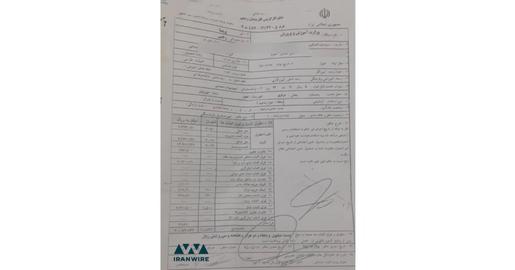

With the third marriage, another disaster lay in wait for Parisa. Simply put, she said, “He tortured me. For example, once when I was sleeping, he put a heated spoon on my foot because I’d slept past the call to morning prayer. Or he savagely slashed my arm with a knife from elbow to wrist. The last time, he poured boiling water on me. I fainted and then called my uncle and my cousin. They came and took me to the hospital. My breasts, my belly and my thighs were badly burned. I was kept in for three days on Taleghani Hospital’s burns ward. It was there that I learned I was two months pregnant.”

The pregnancy did not deter her husband. He agreed in principle to a divorce, but made her pay him twice first. Despite all the violence, says Parisa, the tribe’s chief stood against the divorce: “He told my uncle to return me to my husband’s home. But this time my uncle supported me.

“A while later I escaped to Abadan with my mother. After some time one of my brothers called and said that things had quietened down. But after six months it all started up again. Once again, he demanded money. This time, accompanied by my brother, I went to Hamedan for a few months. But he sued me. He had my address. I received one threat after the other. I had to go back, but I had no more money to give him.”

The Escape

Parisa decided to escape. She and one of her brothers went to Tabriz, the capital of the northwestern province of East Azerbaijan. Two months later her third husband began to threaten her mother, telling her the house would be set on fire. Eventually in late summer 2016, Parisa crossed the border into Turkey with her brother.

“There was no other way,” she said. “I would have been killed if I were alone. During the first year I made money by cleaning houses and stairwells. Now I work as a copy editor for a book publisher. The threats have not stopped. And I have no rights either.”

She and her brother had entered Turkey legally, by bus, before submitting their asylum requests with the UN Refugee Agency. Twelve months later UN officials. But then the Turkish Immigation Agency blocked the process.

According to Turkish law, waiting asylum seekers are forbidden from working. Like in other countries they have no choice but to take on jobs illegally to get by, often working long hours on sub-standard wages and with no benefits or security. For Parisa, the strain of this has been compounded by her husband’s incessant contact.

“Two years ago,” she said, “at the same time as my mother was being harassed, my phone number and address in Turkey were compromised. I received many threats. Even my cousin sent me money and advised me to get out of Turkey. He told me that if I remained, I would definitely be killed, and my tribal brothers who knew this were OK with my murder.

“I gave the money to a trafficker. But after two months of running me around he took the money and disappeared. Once I saw him by chance in a shopping mall. I called the police and filed a complaint, but the judge let him off, and my cousin’s money went up in smoke. The Turkish government did nothing to support me.”

The Rejection

Parisa is now facing a deportation order – one that she knows could be tantamount to a death sentence. Femicide in Iran, especially in tribal groups where naked patriarchy is often exerted against women, is a shockingly regular occurrence and one that carries little risk of reprisal for the perpetrators. In addition, custody of her child legally belongs to a grasping, abusive and obsessive man. She also has no money to escape from Turkey illegally.

Her story is one of thousands but IranWire is consulting with lawyers and launching a public call for anyone who can come to her aid in a meaningful way. Please share this story and contact us if you’re able to help.

This article was written by a citizen journalist under a pseudonym.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments