Yesterday Iran’s security forces raided the home of veteran activist Narges Mohammadi. She was arrested alongside the photographer and women’s rights defender Alieh Motallebzadeh, who like Mohammadi was on a leave of absence from prison at the time.

The rearrest had been scheduled for Tuesday despite the fact that Mohammadi was out for heart surgery. The person who had posted her collateral bail, she told Radio Farda, was also now expecting their home to be seized as she had refused to go back voluntarily.

The day before, April 11, Mohammadi had posted on Instagram: “Tomorrow, April 12, I am going to return to Qarchak Prison.”

The latest case against her saw her sentenced in 2021 to eight years in prison and 74 lashes by Branch 26 of Tehran’s Revolutionary Court, all for having spoken out about her treatment – including sexual abuse – during her last spell in jail. This is her remarkable story so far.

.

***

Narges Mohammadi is, among other things, the spokesperson for the Defenders of Human Rights Center and a fearless public advocate for women’s political and civic freedom in Iran. She reported on Instagram that as “an act of civil disobedience”, she was not going to present herself at prison despite a summons six days earlier.

In May 2021, in an interview on Clubhouse, Mohammadi reported that she had just been sentenced to 30 months in prison, 80 lashes and two fines for “propaganda against the regime by releasing a statement against death penalty”, “sit-ins at prison office”, “disobeying the warden and prison officials”, “breaking windows” and, remarkably, “defamation by claiming torture and beatings”.

Earlier in February 2021, she had posted a video about the sexual harassment of women in prison by officials and interrogators. She had also published a book of interviews with female prisoners about their experiences of solitary confinement, called White Torture. In the summer of 2021 Mohammadi was arrested and beaten after taking part in a rally to highlight the brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters in Khuzestan.

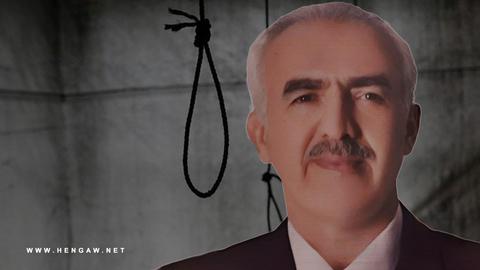

She was then rearrested by security forces on November 17, 2021 after she attended a vigil in Karaj for Ebrahim Ketabdar, a 30-year-old father-of-two who was shot dead during the November 2019 protests. She had been out of prison for just 12 months by then.

From there, she spent two months in solitary confinement in Evin Prison. She was then transferred to Qarchak Women’s Prison in Varamin, a squalid and overcrowded facility where reports of overcrowding and sexual violence by guards are common.

Her husband Taghi Rahmani, who now lives in Paris, called his wife's transfer to Qarchak a form of “vengeance on liberty”. On January 23, 2022, he reported that Mohammadi had been sentenced anew to eight years in prison, 70 lashes and two years’ “deprivation of communications” in a trial that lasted fewer than 10 minutes.

A Twitter Storm

In early April, amid all of this, Mohammadi gave an interview to Jason Rezaian of The Washington Post – himself a former prisoner of the Islamic Republic – about international sanctions on Iran and Iranians’ need for “serious support” from the West. In any negotiations with Iran, she said, “Make human rights a priority.”

She went on: “Economic sanctions, because they weren’t targeted or based on adequate knowledge of the state, weakened Iranians economically more than they weakened the Iranian regime. In fact, they strengthened the regime, and hardline groups in the country, including the IRGC. This did not benefit democracy in Iran.”

She then emphasized the same points on her Instagram page, writing that any future sanctions had to target human rights violators first and foremost. The interview and accompanying posts prompted a tide of criticism on Twitter.

Two days later, Mohammadi gave another interview to Iran International in which she said that some of her points had been ignored in the attacks. She re-emphasized that she supported sanctions against human rights abusers, but not those that “weaken the people”.

Taghi Rahmani told IranWire that social media infighting only benefited the Islamic Republic. “A

person might say something in an interview that you might not agree with,” he said, “but instead of attacking that person you can express your own view, especially if you have access to the media, whether inside Iran or outside it.

“But if you take action through destructive attacks, you are part of the security game. One of Narges’s features is that she has never attacked anybody. This takes self-restraint. Those who are not now in prison, have not been sentenced to prison, have a better opportunity to express their views than Narges.”

Playing Into Tehran’s Hands

On March 16, BBC Persian published a top-secret memo from the Intelligence Ministry’s Director of Information and Legal Affairs to the judiciary about how to discredit dissenters and critics of the Islamic Republic. The excerpt published by the BBC contained suggestions about how to deal with Narges Mohammadi specifically.

Rahmani told IranWire the same document had nine other clauses as well. “It cites the names of other individuals and suggests, for example, do not arrest so-and-so and ‘We’ll ruin his reputation’. Or it’s suggested that another person be released so they’ll collaborate, or have their ‘potential’ used elsewhere. With the attacks against Narges, suggestions by the intelligence Ministry have come about.”

Twitter wars, he said, were “exactly what the Islamic Republic welcomes. Anybody who is wise would not fall into the trap. At the same time, these brawls push the main points to the margins. People accuse each other of having bad intentions… and don’t change their positions because, if they do, they’ll lose followers. This is a dangerous game and the Islamic Republic knows this better than you and I.”

This was not the first time Narges Mohammadi had been the subject of backlash online. In October 2020, on her release from prison after six years, people questioned her made-up appearance. In an interview with IranWire at the time, she said she wasn’t surprised by the attempt at shaming: “Everyone has a right to privacy that others should not encroach on. But because it’s in dispute, I’ll say this: struggle is a part of our lives.

“I am a woman, and part of my life, inside or outside prison, is what you saw, and it has nothing to do with a person’s resistance or a person’s steadfastness in their ideals. In Zanjan [Prison], I was informed: ‘We have a case against you for starting a dance in Evin Prison after lights out.’ I told them I’d keep doing this even if they considered it a crime. I have maintained my life, my femininity and my motherhood, and I will continue to struggle with all these qualities.”

Pulling a Family Apart

Aside from her activism, Mohammadi, born in 1972 in Zanjan, has a degree in physics and was formerly a professional engineer. She co-founded an organization called the Enlightened Student Group while in university and was arrested twice even in the course of her work there.

In 1976 she went to work for reformist journals, and in 2003 she joined the Defenders of Human Rights Center, founded in 2000 by the Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi. She was also formerly president of the executive committee of the National Council for Peace, an anti-war and pro-human rights organization founded in 2007.

Mohammadi and Rahmani married in 1999 and have twin children, Ali and Kiana. Mohammadi was first arrested the year they were wed during student protests. She was arrested again in 2004 for her activities on behalf of what were termed “religious-nationalist” families. Then in 2010 she was taken to prison, and in 2011, sentenced to 11 years for “activities against national security”, “propaganda against the regime” and her membership of the Defenders of Human Rights Center.

Until 2019 she was held at Evin Prison. But after co-organizing a sit-in over the massacre of protesters in November 2019, she was transferred to a prison in Zanjan. Her health badly deteriorated there and she was banned from phone contact with her family. It wasn’t until 11 years later that her children would hear her voice again.

Taghi Rahmani told IranWire that one the most damaging actions taken by the Islamic Republic against Mohammadi had been taking her job away from her. From 2002 onward she had been an inspector for the Iran Construction Engineering Organization, an NGO that provides engineering services to the public. After she was arrested she was given a choice: keep your job or continue your civic activities. Mohammadi, of course, chose the latter.

“Even the Shah didn’t do this,” Rahmani said. “If somebody was sent to prison then, he could have his job back after he was released. The law wouldn’t permit otherwise. Even the reformists who were imprisoned [under the Islamic Republic] could have their jobs back after their release. But they took away our livelihood for fighting. They never allowed me to have a job. Before the revolution, the Bazaar helped the activists; now it provides no help. An activist can only get money from the Islamic Republic, or from America.

“I’ve not seen Narges for 10 years and the children have not seen her for seven. A family means being together. The Islamic Republic is making an example of us.”

In 2018, Mohammadi wrote that in four years, she’d heard her children’s voices 114 times without being able to see them. Later, after they joined their father in France, she said that she fondly remembered their last meeting. Then the Iranian judiciary cut off her access to the phone.

“The children are denied events like having a meal together, conversing, or sharing their problems with their mother,” Rahmani said. “Their mother isn’t beside them. One tries to cope, but the harm can’t fully be repaired. The time for many of these events is gone and it isn’t coming back.

“I don’t know how it will affect the children’s future. I can only mitigate the harm by constantly talking to them and explaining the situation. I can only hope that when they grow up, the children can understand. Right now, they accept it. We’re lucky they are like this.” The twins, he says, have told him: “When Mom is here, Dad is not. When Mom is not here, Dad is.”

Now, he says, “Narges has to go back to prison and won’t be allowed to speak with them again. Why this double punishment? They aren’t allowing it in order to put more pressure on her, them and me.”

While she was outside, Narges Mohammadi refused to leave Iran illegally. She sought official permission to leave, but to no avail. “I have been on the same path since 1992,” she told IranWire in 2020. For me, struggle and resistance are defined as my course in life, and this is the course I have chosen.”

Narges Mohammadi’s Awards and Accolades

2021: Nomination for Nobel Peace Prizeby Amnesty International and two members of the Norwegian parliament

2021: Winner of Grand Reportage Competitionat the International Film Festival and Forum on Human Rights (FIFDH) for White Torture

2018: Andrei Sakharov Prizefrom the American Physical Society "for leadership in campaigning for peace, justice, and the abolition of the death penalty and for her unwavering efforts to promote the human rights and freedoms of the Iranian people, despite persecution that has forced her to suspend her scientific pursuits and endure lengthy incarceration."

2016: “City of Paris” Awardby the Mayor of Paris and Reporters without Borders (RSF)

2016: Human Rights Award of the German city of Weimar

2015: Italy’s Galileo 2000 Foundationprize for contributing to peace

2011: Per Anger Prize, the Swedish government’s international award for human rights, for her publicly struggle for human rights and the freedom of women in Iran

2009: Alexander Langer Award, named after the Italian peace activist Alexander Langer

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments