Back in March, I took part in a webinar on propaganda in Nazi Germany, in which we talked about youth as a target group for the Nazis’ political indoctrination. During the webinar, I kept thinking about how the Nazi propaganda machine was in some ways comparable to, and in others different from, that of the Islamic Republic of Iran. At the end of the discussion, I briefly addressed what I saw as the primary difference between the two states. I didn’t have much time to explain my ideas, so I want to expend some words here on doing so.

Looking at the Nazis’ propaganda architecture, and then that of the Iranian regime, it becomes apparent that they diverge in terms of what we might call “channeling emotions”, and in their presentation of a utopian future.

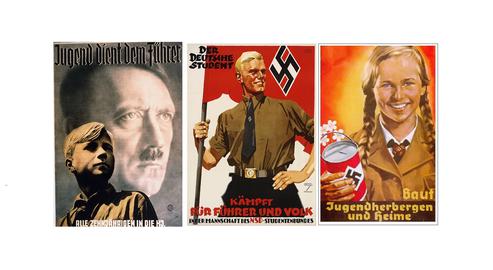

In the Nazis’ political and ideological propaganda, the youth were posited as the driving force behind the movement, and the Nazis as reliant on youth and vigor to achieve their goals. From the 1920s onward, young people were therefore the principal target audience. Youth-centred propaganda depicted Nazi Germany as fresh and hopeful, a dynamic society on an irrepressible forward march.

Children and young people were introduced to this idea through play, in extracurricular activities and sports competitions. By 1936, membership of Nazi indoctrination groups such as the Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls was mandatory. Youngsters were invited to weekend activities, post-school meetings, excursions and weekend hikes. In so doing they would gain a sense of independence from their families and personal agency. But they were also trained to be obedient to the Nazi Party.

In propaganda content, too, the Nazis prioritized youth, and directing the passion and force of the new generation toward an engineered future and an ideological goal. Back in the 1920s, Hitler had infamously written in Mein Kampf: “Whoever has the youth has the future.” The content of Nazi propaganda, concurrent with the re-shaping of the national curriculum, focused on the future of German society and the emphasis on the role that the “right” sort of young people would play in shaping it.

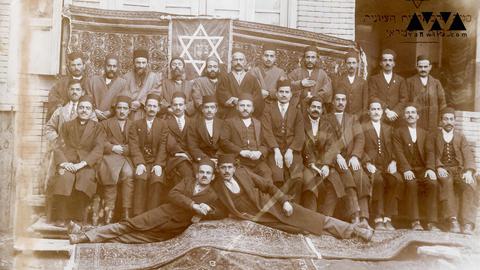

By contrast, in today’s Iran, the Islamic Republic’s propaganda machine has by and large failed to articulate a future that might come about as a result of passion, motivation and hope. In the first decade after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the state exerted great effort on involving young people: first via the revolutionary committees, then the paramilitary Basij, then as recruits in the Iran-Iraq War from 1980 to 1988.

But then and in the decades that followed, the effectiveness of Iranian state propaganda rapidly dwindled. Today, it manifestly fails to attract or mobilise the youth, at least at the national level. With the memory of the 1979 revolution now overshadowed by recent events, and the growth of disillusionment with the utopia promised by Ruhollah Khomeini, the Islamic Republic can no longer offer a realistic, imminent or widely desirable vision of the future.

Official studies and statistics betray a growing sense of hopelessness and desperation among young Iranians. A poll from 2018 assessed young people’s hope for the future as being at a historic low. More than 64 percent of respondents agreed that life in the country was getting worse by the day. In such conditions, what propaganda successes can the Islamic Republic claim?

Here, then, we observe a major difference between the propaganda drives of Nazi Germany and the Islamic Republic of Iran: where one broadly succeeded, the other failed to attract and keep the loyalty and buy-in of the next generation.

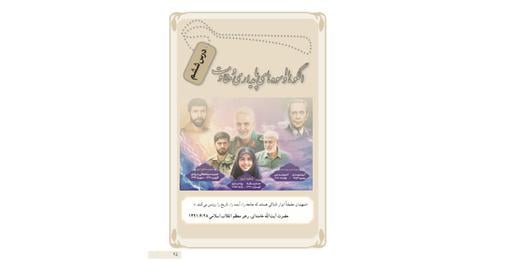

The propaganda architecture of the Islamic Republic is old. That is to say, it was formed in the absence of youth. Passion, zeal, energy and happiness have long been viewed with suspicion and pessimism by the dominant, Islamist cohort. The way the Iranian regime regards the “ideal” religious, pro-regime young person is betrayed in TV serials, movies, media and government discourse, and by contrast, the widely-promoted image of the ideal young Basiji Shia is quiet, dispassionate and static.

In a political culture built on notions of martyrdom, oppression, resistance and passive heroism, but dominated in reality by ranks of decrepit clerics, it’s no surprise that youthful enthusiasm is in short supply today. Passion is repressed, desire straitjacketed, young bodies constrained and/or symbolically punished in religious and funereal rites. With so much of the youth propaganda themed around death and martyrdom, it often appears as though the sole approved channel for youthful zeal in Iran is the so-called Passion of Imam Hossein: inward-facing, focused on the hereafter, otherworldly and immaterial.

There are undeniable similarities between the propaganda regimes of Nazi Germany and the Islamic Republic. Among others, we can name the restriction and destruction of alternative media, portraying divergent or opponent messaging as lies, using school textbooks and educational programs to indoctrinate children, and using statues, murals and public spaces to emphasize both the role of a given leader and his inaccessibility.

But there are also fundamental differences in their content and behavior. These are rooted in the two states’ divergent approach to humanity, life, and the wider world in which they operate.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments