Iranian-American Bahiyyih Grant remembers her grandfather's stories of his childhood in Iran, where his family faced discrimination because they were Baha'is. These stories, and those of Mona Mahmoudinejad and others who were killed because of their faith, have meant that she never takes her right to free speech and religion for granted.

“Read my book if you want to hear more stories,” my maternal grandfather tells me after recounting a story from his childhood in Iran. We always beg him to tell another, and eventually, he will give in.

“When I was growing up in Iran,” he says, “my family was always targeted by the other villagers of Nayriz because we were Baha’is. I remember every year during the month of Muharram, the Shia Muslims of my village would beat themselves with chains as they walked through the dirt streets of the town on their way to the mosque. On those days, my family would huddle up together in our small home in the Baha’i section of the village. With our furniture pushed against the door, we would sit in silence, listening to the moans and cries of our fellow Nayrizis outside of our door. They would try to break into our home, pushing their bodies against the door, calling us dirty. On one occasion, we barricaded ourselves inside our home but realized that our dog was still outside. The next day, we found our dog killed.

“The hatred against the Baha’i community was not only manifested in violence and slurs. I remember going to the bathhouse with my mother every Sunday. The bath was refilled every Monday, and the officials of Nayriz did not want the other villagers to have to bathe in water that had been dirtied by the Baha’is.”

Throughout my whole life, I have heard stories and read news about the plight of the Baha’is of Iran. I know the story of Mona, who was only 17 years old when she was martyred by the government of Iran for refusing to recant her faith and teaching children’s classes, which I teach here in America as well. I hear the news about Baha’is, such as my cousin who recently got a graduate degree in music at the University of Georgia after being denied admission at Iranian universities just because of his beliefs. I am all too aware of the arrests, the interrogations, the imprisonments, the ransacking of homes, and the countless other microaggressions that my Baha’i brothers and sisters and blood relatives in Iran face on a day to day basis.

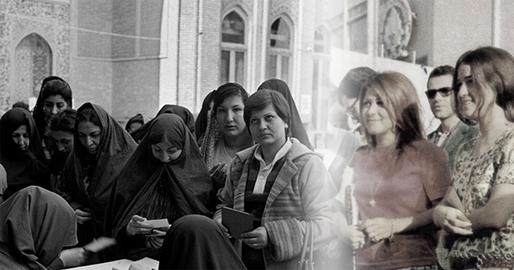

My maternal grandparents both immigrated from Iran to America in order to escape persecution and receive a higher education. My grandmother later told her father that she was never going back to her homeland now that she had tasted freedom. My grandfather is not all that keen on returning either. Since they came to America, they have been given freedom of speech and religion. They have made deep connections with people of every religion, class, and race. My grandfather can write and publish his books about the history of the Baha’i faith and my grandmother can go to her favorite coffee shop every day and talk to the other customers about any topic, including religion. For my grandparents, America is a land of freedom. They are constantly telling me how Americans take their First Amendment rights of freedom for granted. This deeply resonates with me, especially when I compare myself to Mona, who taught children’s classes about the Baha’i faith and spiritual virtues, just like I do on a weekly basis. The only real difference between us is that she was in a country in which she was martyred for her actions. Because of this, I feel the obligation to take every opportunity I can to be confident and steadfast in my faith.

Hearing the stories of my grandparents and the countless other Baha’is who are persecuted have changed the relationship that I have with my religion greatly. My grandfather was my age when he had to take shelter behind the barricaded door of his home. Mona was my age when she kissed the rope that was destined to end her life. So surely I can take pride in my religion. Surely I can have the courage to mention that I am part of the Baha’i community. I have the freedom to practice my religion in America, and this is a freedom that I cannot take for granted. Because of this, I try my best to bring up the Baha’i faith and incorporate its teachings into my life as much as possible, even though it can be scary to be different sometimes. When I integrate my religion with my day-to-day life, I feel a connection with my ancestors and relatives in a way that provides me with a greater steadfastness and confidence in my faith.

Bahiyyih Grant lives in Atlanta, Georgia, where she attends school and teaches the values of the Baha’i faith to children. Foreigner: From an Iranian village to New York City, and the lights that led the way, by her grandfather Hussein Ahdieh and Hillary Chapman, tells one man’s personal story of the Bahai’s of Iran

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments