Israeli-Iranian folk singer Maureen Nehedar not only challenges the ongoing practice of child marriage in Iran, she helps give a voice to its damaging legacy, writes Marjan Keypour Greenblatt

I recently came across a TV series in the Islamic Republic called “Little Engineer.” Javad, the protagonist, appears in the luxurious home of Mojgan Abbasi, where he takes part in an uncomfortable tea ceremony and asks Mrs. Abbasi for her daughter’s hand in marriage. What is most uncomfortable about the scene is not the mere request for permission, but rather the reality that Javad and Mojgan both appear to be under the age of 15 — as well as the tears that stream from Javad’s hairless cheeks when Mrs. Abbasi rejects his request to marry her daughter. Later in the series, a transformed Mrs. Abbasi has submitted to the children’s decision to be together, accompanies them on an outing and gives them time alone.

The TV series is no accident. It is consistent with the message conveyed by Dr. Hassan Rahimpour Azghadi, a member of the Islamic Republic’s High Council for Cultural Revolution. Azghadi recently stated publicly that there should be no age restrictions on marriage, an explicit endorsement of the anachronistic practice of child marriage. And so the prime-time portrayal of a romanticized union between two adolescents is not some coincidence. It is the deliberate implementation of government policy as the regime seeks to socialize and normalize this antiquated convention, despite the fact that it clearly violates the basic rights of children, sacrificing their adolescence and stifling their development.

But before this television series and the regime’s explicit policies, there were already bedtime stories and folk songs that planted the idea of these practices in the collective culture and subconscious. I was reminded of this connection not long ago at a most unexpected time and place: the solo musical debut of Israeli-Iranian folk singer Maureen Nehedar in New York.

Lullabies, History and Women's Lives

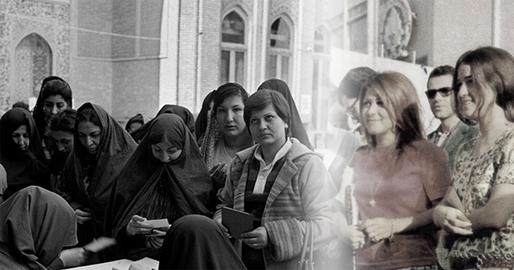

When a group of over 300 mostly Iranian-Americans appeared at a local venue to hear the singer, they didn’t know what to expect. Perhaps some people were expecting a night of carefree dancing and gher, the signature hip movement of Persian dancing, enjoyed and practiced equally by both men and women. But Nehedar offered something totally different.

She arrived without bells and whistles. There were no electric instruments. Her accompanist was reportedly refused a visa. It was just Nehedar, modestly dressed in a long floral tunic, bearing an acoustic guitar and a sazboosh — a traditional string instrument also known as a cumbus.

Nehedar assured the audience that, if the song is good, that’s all you need. And she quickly seized the crowd with her captivating voice, roaring with a sound rarely heard. It was a simple, unadorned but extraordinary voice that transformed the audience before my eyes.

Nehedar is an impressive woman on many levels. Not only does she possess a powerful voice, the singer has a deep understanding of what she is singing and the weight that her music carries. Trained as a professional musician, she has dedicated herself to preserving Iranian folk music and its rapidly disappearing Judeo-Persian variant. And she is doing so with the highest standards, so that her music feels like reading a history book that must be written even if it is not referenced until it’s needed. Her authenticity is so powerful; few musicians in the modern world can boast such power and richness.

Halfway through the concert, Nehedar introduced a traditional Iranian lullaby. Persian lullabies or lalaee are perhaps the saddest category of the Iranian musical tradition. Many lyrics depict lonesome mothers lamenting their traveling or working spouse and babies who refuse to give their mothers a quiet respite.

But Nehedar described these tragic figures not as adults but as young mothers, perhaps 12 or 13 years of age — essentially children raising children. She characterized lullabies as possible moments of solace and self-expression, moments when these adolescent moms could grieve for their vanished hopes and interrupted lives. These were possibly the only permitted form of expression for calming the children and placating the mother’s soul.

And so Nehedar continued, talking about her beloved grandmother, Homayoon, a quiet and traditional lady who was forbidden from singing in public despite her beautiful voice. She talked about how she recorded her grandmother’s voice in one of her albums and then delivered her own rendition of the lullaby, a song that Nehedar described as “the soundtrack of our lives.” It was emotional, powerful and profoundly tragic.

A Shared Sorrow and a “Cruel Culture”

As Nehedar sang the lullaby, she unlocked emotions that had been lodged in the subconscious of so many people in the room. There was no chatter in the audience, no errant cell phone rings. Tears streamed down faces of women and men alike. And yet it wasn’t all nostalgia, but rather a cathartic release of pent up sorrow that had been held in the hearts of mothers and their sons and daughters for generations. It was as if a combination of deep trauma – untreated postpartum pain, social isolation, marital abuse, domestic violence – which mothers had inadvertently passed on to their children over generations was suddenly alleviated.

At a private gathering of local women organized the next day, Nehedar opened up about her journey. She explained how she discovered and reinterpreted Iranian folk music even as she developed an increasing degree of skepticism for the lyrics. She recited the words of a traditional wedding song:

the bride’s neck is white as crystal... the groom wants to visit her... 40 camels are carrying her dowry... she’s walking delicately.

Nehedar acknowledged that these are beautiful words, but also said that beneath them lies a “cruel culture.” Everyone sings about how beautiful the bride is, but has “anyone sung about her soul? How old even is this bride?”

Hearkening back to her comments at the concert that preceded the lullaby, Nehedar shared that her own mother was married off at 15 and her grandmother at nine. These revelations prompted a spontaneous wave of confessions from the glamorous women at the exclusive gathering. They all suddenly shouted out the ages of their mothers, or about their own marriages.

“Is this really a happy occasion? Isn’t this just a business transaction?” asked Nehedar, recognizing that poverty was a cause for early marriage in certain communities.

Indeed, in the last century, many Iranians have tried to correct the social demons that once repressed women and girls from a young age. Many chose the path of literacy. Other families who had suffered from the damages of child marriage resolved to protect their children by delaying the union. Others pursued their financial independence, such as Nehedar herself, earning a living and standing on her own.

At a time when the Islamic Republic is encouraging a revival of child marriage, Nehedar’s music is an antidote that reminds us of the perils of this practice. Her songs move the listener, not as entertainment, but as a moment for introspection. They provide a remarkable journey to the past that underscores the peril of the present. Her music evokes the precious cultural heritage of our past even as it reminds us of the humanity and justice that we must seek in our future.

Born and raised in Iran, Marjan Keypour Greenblatt is a human rights activist who advocates for women and minorities

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments