Much has been written and said about domestic violence against women around the globe. It has pressured policymakers and other stakeholders to pass laws in various countries, and to create support networks in an attempt to control this widespread problem. However, less emphasis is given to the various aspects of state-sponsored violence against women. The problem is rife in my home country of Iran.

In Iran, ever since the early days of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which resulted in the establishment of the Islamic Republic, revolutionary leaders have turned to Islam to impose various forms of violence against women, and to justify the legalization and institutionalization of it. These revolutionary leaders began such efforts against women primarily through issuing fatwas (Islamic orders), and later by legislation.

For many years now, Iranian women’s rights advocates have struggled to persuade the Islamic Republic to reform these discriminatory laws. Many of these advocates have paid a high price for their activism.

The Mandatory Islamic Veil

A few days after the victory of the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s clerical leader, made it compulsory for women to wear the Islamic veil or hijab.

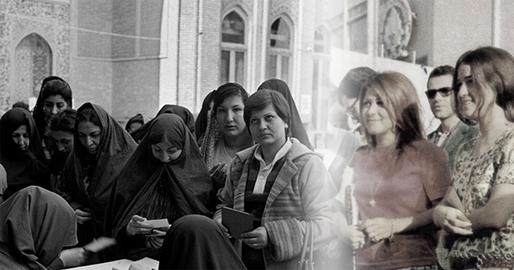

For the first few years following the decree, Iranian women publicly staged their objection to and resistance against the new law. They organized protests and used other peaceful means to reject this form of repression. However, given the institutionalized and violent enforcement of the mandatory veil, ultimately, Iranian women had to submit to this state-sponsored form of discrimination.

Before the Islamic Revolution, a large number of Iranian women used to wear the Islamic veil through choice, while many others did not. Regardless, women had the right to choose, and the government did not interfere.

However, under the Islamic Penal Code that was passed after the Islamic Revolution, not wearing the mandatory veil became a crime punishable by law. Punishment initially meant flogging or a financial penalty, and later, two months of imprisonment or a financial penalty.

Special police forces enforce mandatory Islamic veils, patrolling the streets, and stopping and often detaining women who do not wear the veil according to the guidelines issued by the state (this violation is also termed as wearing “loose” or “bad hijab”). Despite all these efforts on behalf of the state, 37 years on, the Islamic Republic and its repressive affiliated entities have not yet managed to make Iranian women completely adhere to the mandatory veil law as Khomeini had wished. While women do wear the mandatory veil, many of them have added fashion elements to the veil in ways that the state cannot control no matter how hard it tries. While all women wear the veil in public venues, many of them wear “bad hijab” — fashionable, loose-fitting, and/or colorful veils, as well as wearing various and often extreme or dramatic makeup, have gradually evolved as a way to peacefully resist against the repressive nature of the mandatory veil. Furthermore, facial plastic surgery has become extremely popular in Iran — it has one of the highest numbers of cosmetic surgeries in the world. Nose jobs are particularly popular, and the surgery has emerged as a way of resisting state efforts to repress women’s appearance in the name of Islamic chastity and modesty.

Gender Segregation

Under Iran’s Islamic Penal Code, police can arrest men and women who are not mahram (family) if they appear in public together, including traveling in cars together, dining together in restaurants and attending public events together. Punishment for gender intermingling between non-family members can include flogging.

Nevertheless, Iranian men and women, who have studied together in universities for around 100 years, refuse to let these laws get in the way of their peer-to-peer interactions. Similarly, men and women socialize and spend time together in private spaces such as homes, or in public venues. Meanwhile, the Islamic Republic has stepped up its efforts, even going as far as sending its moral police into people’s homes to interrupt gatherings and parties, and often detaining hosts and guests.

Despite all its efforts over the last few decades, the state cannot claim to have succeeded in its goal to prevent men and women from interacting and socializing. The Islamic Republic’s moral police forces seem only able to identify and repress case-by-case co-ed gatherings and parties, or to arbitrarily arrest people in the streets — most of which can actually often be resolved through bribery. The Islamic Republic has simply failed to segregate men and women in public and private spaces as defined in the Islamic Penal Code.

Restrictions in the Arts

Since the early days of the Islamic Revolution, women have been forbidden from singing solo or playing instruments. Iranian society has responded to these limitations by hiring private music teachers for their daughters whenever possible. In fact, before the revolution, when there were no such limitations, many families paid little attention to their daughters’ musical education. But now they do. When the Islamic Republic came face to face with this sudden rising desire for music education, it began to issue licenses for music institutions. Most of these music institutions were allowed to accept female students, as long as they abided by Islamic rules and conditions. These included a requirement for female students and teachers to keep their Islamic veil on at all times, and for female and male students not to mingle while engaged in musical lessons.

Decades after the revolution, the Islamic Republic still resists women’s presence as musicians in concerts, and some hardliner groups — some of which may even be connected to the state in an official capacity — physically attack such events, instilling fear among the public.

Similarly, in other areas of the arts, including the theater and cinema, state-sponsored restrictions are rife. Nevertheless, against the odds, artists have succeeded in highlighting the role women role play in these creative areas. As such, the government has not reached its ideal of eliminating women from the performing arts in the name of Islam. Women continue to work as directors, actors, and musicians, and in other arts. Their persistence against the censorship meted out by the Islamic Republic is truly exemplary and admirable. In fact, these women’s ongoing resistance has made the government back off in many instances.

Professional Limitations

Immediately following the victory of the Islamic Revolution and the establishment of the republic, it became forbidden for women to serve as judges. Islamic Republic officials announced that, according to Islamic orders (fatwas) and Sharia law, women do not have the right to become judges. Ten years before the revolution, during the time of the shah, women were given the right to become judges. By the time the revolution took place, more than 100 women were serving as judges in different courts holding various ranks and positions, and at the time of the revolution, there were others who were receiving education to serve as judges in the future.

When the state barred women from serving as judges and this limitation was legally institutionalized, women responded vigorously. Women who had been studying and training to become judges organized a sit-in outside the main court in Tehran. One week into the protest, revolutionary police forces attacked the protesters, kicked them out and added their names to a blacklist, creating further limitations for them as “anti-revolutionaries” for many years to come.

Women could not stop this form of repression from becoming the law. However, women’s rights activists did not remain silent. They continued to object in a variety of ways, including speaking to and writing for the media, and participating in events and conferences. These efforts continued so persistently that finally, after 14 years, some aspects of the limitation were removed. A law was passed that allowed women to serve as judicial advisers in courts, though not as judges. Women still do not have the right to issue and sign the final verdict. It is worth pointing out that Iranian women are particularly interested in pursuing legal and judicial professions in today’s Iran. Their thirst to study law and to become lawyers and legal advisers has consciously put pressure on the Islamic Republic to reconsider some of the limitations against them, even if these reconsiderations have been minimal and gradual.

Limitations in Diplomatic Positions

After the Islamic Revolution, women were forbidden from pursuing certain diplomatic careers, including consular and ambassadorial positions. Furthermore, a school that the shah’s External Affairs Ministry had started for those interested in diplomatic careers closed its doors to women. Thirty seven years later, the Islamic Republic now appoints a handful number of women, who must meet its highly ideological selection criteria for these positions.

Limitations in Sports

Women’s participation in sports has for the most part been forbidden since the Islamic Revolution. However, even though they are still quite restricted, nowadays women can participate in certain sports as long as they adhere to the rule of the compulsory Islamic veil. Women have much fewer facilities for athletic practice and sports events than men do. Additionally, women are forbidden from entering sport stadiums to watch men’s games.

Despite these limitations and against all the odds, women have managed to succeed internationally in a variety of sports. Women’s rights advocates have also worked hard and have paid a high price to push the Islamic Republic toward less discriminatory policies for women in sports. In particular, there has been much civic activism to battle the limitations on women watching men’s sports live at stadiums.

State Violence in the Context of the Family

The laws of the Islamic Republic discriminate against women within the context of the family in many ways. For example, girls bear full judicial responsibility once they turn nine years old (according to the lunar calendar). It is legal for girls to be married at age 13. Unlike women, men have the absolute right to divorce. Men can have up to four permanent wives, and several so-called “temporary” wives. Girls receive half of what boys receive from their parents as inheritance. For their first marriage, girls must have the official consent of their father or their grandfather. If a husband sees his wife making love to another man, it is possible that he can kill both his wife and the man she was having relations with without there being any repercussions. There are no corresponding laws for women. These are just a few examples.

Some of Iran’s family laws were reformed before the Islamic Revolution and became less discriminatory against women. However, after the Islamic Revolution, officials revoked those reforms, as they considered them to be in contradiction with Islam and Sharia.

With the help of discriminatory laws and policies, state violence against women has become institutionalized and enforced in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The current constitution does not allow legal reforms that are not in line with Sharia and Islamic principles as they are defined and interpreted by the leaders of the Islamic Republic.

Therefore, eliminating state violence against women is not really possible as long as a religious government is in place. Many Iranians object to these forms of discrimination and violence, risking their freedom and safety by doing so.

Ultimately, the precondition for the removal of of such legal and institutionalized forms of violence against women in Iran relies on the separation of religion and state. In other words, gender equality is not really possible in the current circumstances of the country, as the legislative structure of the Islamic Republic prevents the introduction of democratic laws.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments

http://dubaiescortss.info/