On July 3, Iran and the French oil company Total signed a contract to develop Phase 11 of Iran's South Pars, which, together with Qatar’s North Dome, is the world's largest gas field. This is the first major Western energy investment in Iran since the lifting of sanctions over the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program.

The Persian Gulf gas field of South Pars holds 8 percent of the world’s known gas reserves and borders on the Qatari field North Dome. According to the contract, the project will start producing gas in 40 months and will add 56 million cubic meters to the Iranian daily gas production capacity.

Total’s share is 50.1 percent of the contract. Of the remaining shares, 30 percent goes to the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) and 19.9 percent to PetroPars Oilfield Services Company, a subsidiary of the Naftiran Intertrade Company (NICO) which, in turn, is fully owned by the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC).

The minority share of PetroPars has provided critics of Rouhani’s government with a starting point for non-stop attacks on the government and on the Total deal. They even tried to derail the agreement in the parliament on constitutional grounds but did not succeed.

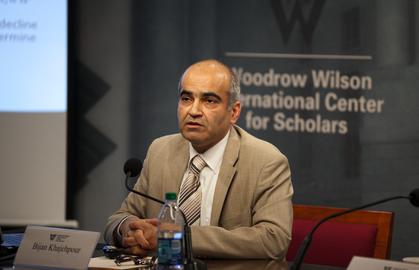

In the fourth article in our series on the Total deal, we talked with Bijan Khajehpour, founder and managing partner of Vienna-based Atieh International, a firm specializing in consulting services to international investors in West Asia, and asked him about the merits of the critics’ claims.

Read part one, part two and part three in the series.

The first and foremost criticism against the Total contract is about Iran’s share of the deal, and that of PetroPars. Why is Iran’s share below 20 percent, the critics ask?

In the new Iran Petroleum Contract (IPC) model, the investment partner enters into a partnership with the NIOC to develop and exploit an oil or gas field. That means that the NIOC and the investment partner agree to share the profits of the project. In the case of the recent contract, the NIOC has signed a contract with a consortium consisting of three companies: Total, the CNPC and PetroPars. It means that in this case we have two Iranian partners: First, the National Iranian Oil Company that owns the project, and then PetroPars, which is a partner in the consortium.

These two roles must not be confused. PetroPars, an Iranian company, must contribute to the investment according to its 19.9 percent share of the project. It must work with the consortium to develop the project until it reaches production and then the entire consortium gets a share of the production to pay for the costs of its investment, plus profits, fees and bonuses that had been agreed upon. Therefore, the claim that Iran receives only a 19.9 percent share of the profits is completely baseless because the initial investment and all the expenses that have been agreed upon will be amortised by the output from South Pars field (for example by the sale of the field’s condensate) in the first seven to 10 years depending on the price of condensate. After that, all proceeds from the project will belong to Iran. Of course, if the consortium continues to manage the field’s production, then there will be a compensation as a “production management fee.”

The deals based on the old contract model — called “buyback” — provide good examples. All buyback investments that were initiated in the late 1990s and early 2000s are now completely at Iran’s disposal. Iran receives one hundred percent of their proceeds. This means that the costs of all primary investments have been paid off and they are now run by companies that belong to the NIOC family of companies.

The important point is that Iran’s real share of a project can only be determined once we know how much of the oil or gas in place can be recovered. This is called the recovery rate and the level of recovery rate depends on technology used, the project and also production management. For example, it has been estimated that, in the case of Phase 11 of South Pars, 15 percent of the value of the total gas and condensate recovery will cover investments and necessary expenses. In other words, 85 percent of the field’s recoverable reserves will be Iran’s.

The other criticism is about Total’s control of the project. In a letter to President Rouhani, the Basiji Students Organization [an affiliate of the Revolutionary Guards] argues that the contract “gives Total complete control not only in the exploration and the development but also in production and utilization.” And the newspaper Kayhan published an article that said the contract was illegal because, according to the Guardian Council’s interpretation of Article 81 of the constitution, foreign companies must own less than a 50 percent share in any project.

[Article 81 of Iran’s constitution states: “Granting of concessions to foreigners for the formation of companies or institutions dealing with commerce, industry, agriculture, services or mineral extraction is absolutely forbidden.”]

It is true that Article 81 forbids granting concessions to foreigners, but the IPC is in no way like a concession. In the oil sector, “concession” in the old sense means that the control of a field is given in its entirety to a foreign entity. The state, or the host government, receives only royalties. As I mentioned, the partner who invests in Iranian projects receives profits from the project for a limited period of time (i.e. for as long as its share of the proceeds covers the principal investment and agreed fees), and then manages the project within a specific framework.

In fact, one of the criticisms international oil companies have against Iranian contracts is that the profits — or what in this industry is known as the “upside” — are very limited. I must point out that in this industry a prevalent framework for contracts is “production sharing,” meaning that the investor develops the field and gets a predefined share of the production during the lifetime of the project.

So we can see that the IPC has no resemblance to concessions nor to profit sharing agreements. On the other hand, without the necessary incentives, the consortium won’t be motivated to use the latest technologies which, in turn, would dampen the recovery rates and be to the detriment of Iran as the host country. This is why the IPC has provided for a series of bonuses to give necessary incentives to the investor/operator of the project.

Another issue is technology transfer. Critics say that Total has no obligations in this area. Some say that the process of technology transfer might take 15 years. They say that because PetroPars is a non-operating partner and will not play a big enough role in the implementation of the project to benefit from technology transfer.

Technology transfer takes place at three levels. First, PetroPars, as the partner in the project, must learn new things and improve its capabilities. A fair assessment shows that a considerable part of current technological capabilities of PetroPars and companies like it come from their past partnerships with foreign companies, especially with European ones.

The second level of technology transfer happens through domestic subcontractors. Iranian laws require that project implementers carry out a considerable volume of their work through domestic subcontractors. Such subcontracts are a good opportunity for Iranian companies to learn new things about oil management and especially about project management.

The third level of knowledge transfer is that these contracts contain a training component. The Petroleum Ministry and other ministries and organizations must take advantage of this opportunity and learn new methods and approaches. So technology transfer takes place at different levels.

Critics have also complained that the contract is confidential. What is your view on this?

The confidentiality of contracts is both customary and logical. Neither the NIOC nor Total (or the consortium partners) want their competitors to learn what has been agreed upon so they can negotiate other contracts independently.

For political stakeholders such as the Iranian parliament, this contract is not confidential. In the past, parliament has had a three-member committee that supervised such contracts. Ayatollah Khamenei himself has a representative at the Petroleum Ministry who supervises contracts like this. So the confidentiality of the contract has two aspects. The first is a business aspect that is customary for such contracts. The second is the political aspect, and the power structure in Iran has its own ways of dealing with this.

Some people have claimed that Total would provide Qatar with secrets about the South Pars gas field. This claim is baseless because geological and technical data about oil and gas fields are too well known for a foreign company to bother with providing them to a neighboring country.

Some members of parliament say that entering into contracts like the one with Total means ignoring domestic capabilities. Do you think this will be the case?

Those who come up with such objections must know that our domestic capability in implementing complex oil and gas projects is limited. The best indicator for evaluating capabilities is the recovery rate in our oil fields. Until now, Iran’s highest recovery rate in oil fields has been around 26 percent, while at this moment, advanced western companies achieve an average of 50 percent. A one percent increase in the rate means 5 billion barrels more oil wealth for Iran (at a price of $50 per barrel, it would translate to $250 billion).

To achieve this goal, our companies must reach a technological and management level that enables them to perform better. This will be done through joint ventures between Iranian and foreign companies. I, too would like to give the projects to Iranian companies when domestic companies achieve this capability level. Meanwhile, as I said, all investment and consortium partners in these contracts are committed to use Iranian subcontractors in these projects. This law is called the “Maximization of Local Content” and its aim is that at least 51 percent of the value of the project be spent inside Iran. But there have even been projects where 60 percent of the investments has been spent within Iran. So the bigger aim — i.e. empowering the Iranian economy and its oil and gas industry — is achieved through such contracts.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments