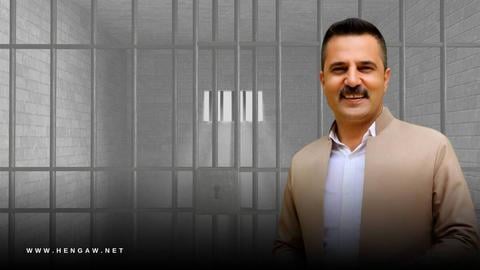

Ehsan Pirbornash, a sports reporter, Sports Bank website editor, and adept social satirist, was apprehended by intelligence operatives from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) on November 7, 2022.

Renowned for his poignant protest tweets and incisive political satires, he faced an 18-year prison sentence handed down by the Revolutionary Court of the northern city of Sari. Ten years of the sentence were enforced.

Behnaz Mirmotaharian, the wife of Pirbornash, revealed through her Twitter account that her husband regained his freedom on February 8 this year. His release was initially seen as part of a wider prisoner “amnesty” but later this turned out to be just a façade.

In recent months, security forces have once again detained numerous journalists, social activists, as well as participants in the Woman, Life, Freedom movement who were released under Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s prisoner amnesty.

Subsequently, this spring, Ehsan Pirbornash left Iran and now lives in Germany with his wife and child.

In an exclusive interview with IranWire, he offers an insight into the circumstances surrounding his arrest and subsequent experiences.

"I asked, 'Where are you taking me?' To which he answered, 'Shut up!'"

In the interview, Ehsan Pirbornash reflects on the protests last year and his eventual arrest, saying, "About a month prior to my arrest, I had already left my own home. Even when in Tehran, I sought refuge in the homes of my relatives. Anonymous calls kept pouring in, to which I never responded. Those were exhausting times, set against a backdrop of revolutionary fervor, both in the streets and in the digital realm.

“The weariness of bouncing between people's residences had settled in. I retreated to Sawadekoh to unwind at our villa. I spent roughly 10 days in my father's village. Upon planning my return, I entered my cousin's car only to have two vehicles abruptly halt ahead, right within the village.

“A young lad extended his hand and announced my arrest, sanctioned by the Sawadekoh prosecutor. I peered at his hand, half-expecting some inscription, but it was an unmarked, blank palm. Yet, showing no warrant, they took me into custody alongside my cousins accompanying me. Their demeanor during the arrest was sour."

Detailing the manner of his transfer to the IRGC detention center, Ehsan Pirbornash recalled, "The initial encounter was marked by a jarring blow from behind as I sat in the car.

“One of them exclaimed, 'Did you believe the nation does not have an owner?' It's in moments like this that the true absence of governance becomes apparent. Had the country been overseen by an authority, individuals lacking both a warrant and proper police attire wouldn't have conducted such an arrest. When I inquired about our destination, their retort was a curt; ‘Shut up.'

"Observing these sorts of arrests and the subsequent declarations from the deputy human rights officer of the judiciary, one can only deem such statements utterly 'absurd'."

“The interrogators' relentless pursuit of a fresh charge: Assault on IRGC personnel”

Ehsan Pirbornash recounts his encounters with IRGC agents: “During the journey, I confronted the IRGC agents, stating that they hadn't apprehended a murderer but rather a writer whose perspectives and inclinations diverged from their own.

“Initially, they conveyed me to a detention center in Zir-Ab city. From there, the forces of the Sari Corps of IRGC arrived to transfer me to their detention center. A displeased reaction met my sight—there I sat, bound with my hands in front, on a chair.

“They [IRGC agents, different form the arresting officers] inquired about the manner of handcuffing, swiftly maneuvering me to position one hand above my waist, the other below, and then shackling me. My physique engaged in contortions akin to a gymnast's routine.

“Presently, I recount these anecdotes with a touch of humor, as those days have receded into history, and we find amusement in reminiscence. Truly, we humorists possess a filter that transmutes even somber occurrences into comical anecdotes.

“Within the confines of the IRGC detention center, I faced the imminent introduction of a new charge: ‘Mr. Pirbornash, are you aware of the accusation for which we apprehended you?’ I responded that it pertained to my content. He chuckled, inquiring, 'This? For your content?' I discerned then that the matter exceeded the scope of my content alone. Swiftly, he exhibited a video on his phone. The footage depicted a robust, robust fellow, who, apart from our shared baldness, resembled me in no other way, assailing a uniformed agent's vehicle in Qaimshahr. Whether this encounter resulted in any casualties remains unknown to me. As I watched the recording, I commented, ‘This guy is handsome. But how am I involved in this?'

“Their persistence betrayed their intent to fold this accusation into my dossier. Subsequently, during further interrogations with the IRGC, I pointed out, 'You previously asserted that my mobile phone was surveilled via telecommunications towers from Tehran to Sawadkoh. Yet, how could you remain oblivious to the fact that I was never in Qaimshahr? Was my phone registered there?'"

‘Let’s stop the car and finish him right here’

Ehsan Pirbornash recounts the experience of IRGC agents conveyed him from the Zir-Ab detention center to the IRGC detention center in Sari: "I was uncertain of our destination. En route, the barrage of blows persisted. A man occupied the seat to my right, another to my left. The individual seated ahead, addressed as Haji, exhibited no passivity; he would frequently pivot back and strike me with his fist.

“Strangely, even the driver occasionally diverted his attention and would beat me. With my head lowered, I discerned that the driver's arm was responsible for these strikes.

Amid the tumult of these beatings, I found myself uttering, 'Please, there are youngsters present; they've subjected me to quite a thrashing already.' My remark triggered a volley of expletives. An agent among them proposed, 'Hajji, why don't we simply finish him, amidst this woodland expanse?' The dynamics of who addressed whom were convoluted. An air of frustration loomed. 'Why waste further time? Where shall we transport him? Let's finish this right here and bury him here.’”

"When I experienced a nervous breakdown, my fellow detainees hesitated to alert the officers"

Ehsan Pirbornash discloses his anticipation of enduring "beatings" from the very moment of his arrest: "From the instant of my arrest, I encountered physical violence, enduring strikes from the Zir-Ab to Sari.

“My forehead swelled under the assault of blows, and my neck was pressed down so forcefully that it remained stiff for several days. However, I continued to brace for more blows. Comparatively speaking, I endured far less than some young individuals who suffered near-fatal beatings.”

He recounts that upon his transfer to the Sari Detention Center, physical torture ceased: "While beatings occurred during my apprehension and initial detention, they ceased during the interrogation phase. Each day brought new rounds of questioning, and I braced for further blows.

“Although none were dealt within the confines of the center, the palpable tension was so immense that it no longer necessitated physical beatings. Once, an agent questioned if I had been subjected to beatings within the detention center. I responded in the negative, elucidating that the severe treatment upon my arrest had created a psychological anticipation of beatings each time they summoned me."

One early piece of news during Pirbornash's incarceration centered on his nervous breakdown within the detention center: "On the fifth day, I experienced a nervous breakdown.

“Oddly, during this episode, I implored three fellow detainees in my cell to summon the guard as I felt unwell. However, the weight of fear upon them was so heavy that they hesitated, suggesting we wait, hopeful the situation would not deteriorate. Astonishingly, even contacting the security guard was a cause for apprehension. Among my cellmates was a 65-year-old man, who also refrained from making the call, cowed by fear.”

Pirbornash reveals that his 13-day confinement and interrogations within the IRGC detention center passed without his captors revealing the location to him: "Throughout my 13-day tenure within the IRGC's Sari Tirkala detention center, its location remained undisclosed.

“I was left pondering my whereabouts. It was fellow detainees who had already ascertained that our confinement was at the Tirkala detention center, a piece of information I learned from them. They informed me that it was the intelligence detention center of the Sari Corps."

Contacting his family via phone was restricted until the third day, and he notes that certain detainees were denied familial communication for up to 15 days: "Variability marked the conditions within the IRGC detention center. In my case, daily interrogations were conducted. However, there were instances where detainees went without interrogations for up to 15 days.

“The reason? They were instructed on the initial day to confess and document as dictated. If these directives weren't complied with, interrogations were withheld. In our scenario, circumstances diverged. My contentions were clear, leaving little room for denial, except for the Qaimshahr IRGC agent's incident, which genuinely bore no connection to me."

Coverage of the Arrest in the Media

When questioned about his concerns regarding being forgotten during his days of confinement and imprisonment, Pirbornash responded, "The fear of being forgotten never crossed my mind, even for an instant. My sole apprehension centered around the anxiety and unawareness of those outside my immediate surroundings.

“Furthermore, I picked up from their conversations that news regarding my situation had reached beyond Iran's borders, and this external coverage proved immensely beneficial. Subsequently, I noticed a change in their approach, as they [agents] encouraged me to use the phone and call outside. They learned that there was someone beyond these walls concerned for my well-being."

The initial charge often leveled against detained journalists during IRGC interrogations pertains to their alleged communication with foreign media outlets.

Ehsan Pirbornash shared, "Thankfully, my financial records were available to me within the detention center. My financial situation was so empty that they remarked said it seemed I did not even have contact with my family let alone engage with foreign media.

“Initially, the accusation centered on my supposed collaboration with opposition media platforms. However, this narrative eventually crumbled when they recognized the absence of any business affiliations. They inquired extensively about my interactions with foreign journalists. My response clarified that we shared friendships and exchanged greetings, but our engagement never extended to collaboration."

"The prison feels like a hotel compared to the IRGC detention center"

Pirbornash is not the first detainee of the 2022 protests to express that upon entering prison, a sense of safety and relief comes to their mind. He shared with IranWire, "Every detainee transitioning from the detention center to the prison feels as though they've entered a hotel.

“In the IRGC detention centers, you're confined to cramped 2 x 3 rooms with three or four others, barely able to take a couple of steps. I endured such conditions for thirteen days.

“Then, I arrived at the prison. Suddenly, we were allowed visits, phone calls, access to a buffet, and numerous new acquaintances to engage with. Contrast this to the IRGC detention center, where you're required to sit blindfolded, facing the phone, granted a mere 30 seconds to speak to your mother, wife, or child through a speaker. The frequency of these calls depends on the prosecutor’s disposition—perhaps once a week or every fortnight. Can you imagine a child understanding that the call is severed after just 30 seconds? This is why I say, transitioning from the IRGC detention center to the prison feels like stepping into a hotel."

Regarding some of the news that circulated during his Qaimshahr prison detention, he commented, "While in prison, there were reports abroad claiming that Ehsan Pirbornash was undergoing torture. This is inaccurate; at least not in Shahi prison (the former name for Qaimshahr). We've heard about torture occurring in Ward 209 of Evin Prison, but such instances didn't occur in our facility."

When these reports surfaced, the prison guards confronted him, asking, "Ehsan, are you being tortured here?" Pirbornash responded in the negative. The guard proceeded, revealing that Pirbornash’s wife had tweeted that he was being tortured in prison. The guard believed Behnaz (Pirbornash’s wife) had authored this claim.

Pirbornash sought clarification from Behnaz, who confirmed she had no knowledge of such a statement. Ultimately, it was discovered that the news was posted by an overseas activist on their Twitter account.

Pirbornash asserts that the publication of such news inadvertently favors the Islamic Republic's narrative: "Consider this perspective: even in our struggle, we should exercise wisdom. I've reiterated multiple times that every stage of my detention and interrogation was unlawful.

“My arrest felt tantamount to abduction. I was subjected to blindfolded interrogations, facing a wall—an approach that is in direct contradiction to the Islamic Republic's legal stipulation against citing confessions obtained under blindfolded conditions.

“Our opposing party [the Islamic Republic] is an entity involved in killings and abductions. In dealing with such a regime, we don't need to amplify the narrative with embellishments.

“When inaccurate information is disseminated, it emboldens the government to disregard actual events like the deaths of Mahsa, Nika, and Kian Pirfalak.”

They asked, "Whom do you imply when you mention 'Dictator'? I replied, “Mr. Jannati”

Pirbornash underwent days of exhaustive interrogations, spanning hours, all centered around the content he shared on his Twitter and Instagram accounts. He recounts, "I explained the context behind each and every tweet I posted. They meticulously printed over 200 pages, encompassing the entirety of my tweets, instructing me to provide explanations.

“Sometimes, they managed to fit four tweets onto a single page. For instance, there was an occasion when they inquired, 'Whom do you mean by the assertion that dictators fail to comprehend?' I casually replied, 'Don't concern yourself with this now.' In response, they asserted, 'No, write!' I wrote 'Mr. Jannati.' To my surprise, the interrogator queried, 'You mean Mr. Jannati?' I assured him, acknowledging its weightiness. He further urged, 'Write, Mr. Jannati.'"

(Ahmad Jannati is a prominent cleric who serves as chairman for both the Assembly of Experts and the Guardian Council.)

“Subsequently, they inquired about the target of my renowned tweet, ‘Until the Internet is cut off...’ I offered a straightforward response, ‘It's quite evident; Minister of Communications, Mr. Azari Jahromi.’ The interrogator burst into laughter, exclaiming, ‘You're even implicating the current Minister of Communications? That's acceptable to write.’”

Pirbornash reveals that at times, the interrogators found his answers amusing, sharing, "Though I was blindfolded, seated with my back to them, incapable of witnessing their reactions, I could sense from the demeanor of their voices that they were stifling laughter in response to my explanations.”

“I recognized that the crux of this situation was an eventual arrest, but what is the cost of life?”

Pirbornash reflects on one of the pivotal inquiries directed his way prior to his arrest, namely, the question of why the government hadn't detained him earlier. He recounts, "Throughout the years of my endeavors in both the digital realm and media, I received numerous messages from individuals wondering, 'Why haven't they apprehended you yet? Don't they understand?' Well, they indeed apprehended me; does that grant you solace? Have I truly burdened your shoulders all this while? [He laughs.] They appeared to find relief, launching hashtags advocating for my release.

“Over the years, I always harbored the notion that one day, my capture would materialize—particularly after the events commenced on September 16, heralding the dawn of revolutionary days. Candidly, I was among the earliest casualties of the Mahsa revolution. I often jest that I suffered a torn cruciate ligament before the season's commencement—akin to a football analogy.

On the very first evening, my forehead was split, necessitating a visit to the hospital. Coincidentally, in the days concurrent with my arrest, I remarked to the IRGC intelligence personnel that if the individual they attributed to me in Qaimshahr was indeed me, he should bear a forehead bandage; why then does his head exhibit no injuries? In any case, I perpetually possessed an understanding of the unfolding events, yet what options lay before me? Should I refrain from writing? Should I suppress my voice? Must I cower in fear? At what cost do I determine our existence?"

“According to some, the street or protests aren't the journalist's domain”

Pirbornash's written output accelerated notably from the beginning of nationwide protests until his eventual arrest.

He reflects that his content shifted away from humor, mentioning, "They informed me that my writing had taken an obscene tone, lacking in politeness. Yet, this didn't faze me; it was my chosen instrument. Just as someone wielded a firearm, inflicting harm and death upon the streets, my tool remained my pen, conveyed through the same style of expression.

“I recollect the year 2009, marked by protests against the presidential elections. Amidst the demonstrations, a fellow journalist opined, 'The street isn't where a journalist belongs.' In response, I countered, 'Likewise, your perspective might find revolutionary articles unsuitable for newspapers.' I consistently urged such individuals to embrace governmental stipends and paper quotas, abstaining from protests."

Exercising democracy within prison walls

When IranWire asked Pirbornash about his experiences inside prison, he shared his endeavor to practice "democracy" within the Qaimshahr prison facility.

He recounts, "For instance, we initiated elections to appoint a 'vakeelband' (representative of the ward from among prisoners) among us. This position was particularly pertinent as some prisoners were either released or transferred to different facilities.

“Certain detainees encouraged me to stand for the role of a vakeelband, and Saeed Rouzbeh and I decided to conduct an election to democratically elect a vakeelband. Subsequently, some individuals jestingly remarked that we had managed to disrupt the prison's grim environment.

“Upon being elected as the prison vakeelband, I donned a t-shirt and proceeded to sweep the prison corridor's floor. A few individuals commented, 'Mr. Pirbornash, you hold the position of a vakeelband; this isn't necessary.' In response, I queried, 'Don't I possess hands?' The image of the respect emanating from our fellow inmates, as they strolled past the bars of neighboring cells, remains indelibly etched in my memory.

“I miss you, but only for an hour”

As he recounts memories from his time in prison, IranWire asks Ehsan Pirbornash if he ever longs for those days. He responds, "There are moments when I do miss those days and the camaraderie of fellow inmates, but not to the extent that I desire to return. Perhaps, if they could assure me that I'd spend merely an hour with those same individuals, I'd be willing to leave for that brief duration. However, I would require an assurance of a swift return."

He reflects on the many Iranian prison experiences that have been shared online, , "At times, individuals recount positive aspects of their time in prison, evoking attacks from certain quarters. These critics claim that such stories are an attempt to gloss over the Islamic Republic's actions. Personally, I've never encountered such attacks, but I've observed many young individuals being subjected to such backlash for sharing their prison narratives."

On the flip side, some individuals detail the harsh conditions of prison life, leading to accusations that they aim to deter people from participating in protests. "So, what's the appropriate course of action?” Pirbornash asks. “If you speak positively about your experiences, you're targeted. If you highlight the harshness, you're accused of fearmongering."

"Both sides reflect the reality of our prison experiences. We endured days when duelling siblings, overwhelmed by the stress, resorted to physical altercations. Conversely, we had moments of laughter so profound that we felt guilty for finding joy amidst such adversity. I often chastised myself, thinking, 'How can you be laughing while your family is grieving outside?'"

Pirbornash recounts a poignant incident when he conversed with his wife and learned that their son, Kian, had been taken to a child psychiatrist and consultant: "Behnaz informed me that our son wasn't well; he had rubbed his lips against his sleeve to the point of injuring himself.

“He needed guidance. I broke down at that moment, openly crying in the presence of fellow prisoners and guards. The atmosphere during those times was far from humane; the news we received was anything but normal.

“When you realize that your child, who eagerly awaited your return just two hours later, continues to talk to you on the phone two months later, you feel an overwhelming sense of distress. How could I not cry when I found myself facing an 18-year prison sentence, with the knowledge that I'd have to serve a decade of that term?"

Leaving Iran: “It's as if I've left my ailing mother alone”

Pirbornash has now left his homeland to emigrate abroad. He reflects that in recent years, he contemplated a short-term move, but the trajectory shifted after the protests: "Here, on one hand, you have newfound freedoms for your family, yet on the other, you're in exile. The day I made the decision to depart Iran, I still believed I was banned from leaving. The lawyer had informed me that my two-year travel restriction, along with the concurrent 18-year prison sentence, had been lifted. In all honesty, upon leaving the country, I realized that they would rather have us exit and not linger within the nation at all.

“The day I resolved to depart Iran, I talked with a close friend. I expressed my intention to leave; we shared tears. He advised me to seize the opportunity abroad and pursue endeavors I couldn't fulfil here. In response, I bared my soul, admitting, ‘It feels like I'm abandoning my ailing mother to fend for herself.'"

"Truly, if the matter solely pertained to myself, I wouldn't have chosen emigration at all. I reached a juncture where I recognized a dual responsibility: one towards my nation and the other towards raising a healthy individual. My son encountered psychological challenges following my arrest.

“There were days when each morning, upon awakening, I found myself answering my son's inquiries about Khamenei, the IRGC, the government, and the Islamic Republic.

“I reiterated to Kian on numerous occasions that these matters were beyond his scope. I maintained that these are affairs for adults to tackle. Witnessing a child of his age grappling with such weighty subjects deeply unsettled me. The fact that a 7-year-old child should bear the burden of understanding that a figure named Ali Khamenei shoulders the misfortunes of our country deeply troubled me.

“I was once advocating for 'staying and reclaiming,' but I left.' The day has come when I feel compelled to shield this child from the struggle and continue my advocacy in a new phase."

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments