As part of our ongoing commitment to promote and disseminate Holocaust education to new audiences, IranWire hosted a panel discussion last month with Andrea Gittleman, the policy director of the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide, within the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

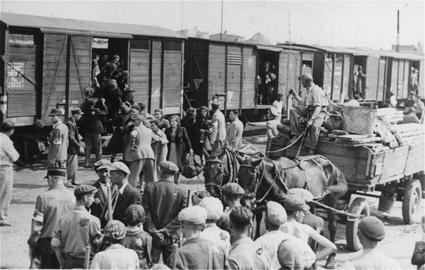

After 1945, as the world recognized the full horror and magnitude of the Holocaust—the systematic attempt to murder every Jew in Europe. The term genocide was coined; the Genocide Convention was adopted; and new norms for international justice and accountability were established.

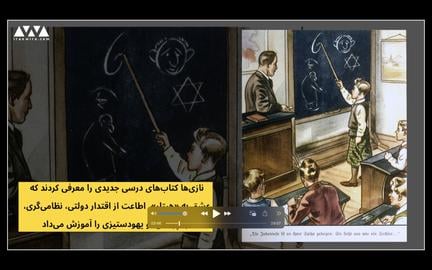

The world’s response to the horrors of the Holocaust has led to a new understanding of international justice and human rights. Islamic Republic officials regularly deny the Holocaust and produce antisemitic and Holocaust denial books, cartoons, films, and other media products. Yet, as Iran goes through one of its most turbulent periods in its modern history and as many Iranians discuss the mechanisms for transitional justice in their country, the lessons of the Holocaust and transitional justice in post-WWII Europe can help them to have a better understanding of the concept.

Since 2021 IranWire has been working with the USHMM in Washington D.C. to counter the effects of distorted public information campaigns by Iran’s current government and to promote Holocaust education - to young Iranians in particular. This has resulted in our joint endeavor The Sardari Project: Iran and the Holocaust.

For the panel discussion, Gittleman was joined by Pegah Banihashemi, a legal scholar and senior researcher at University of Chicago Law School, Ladan Boroumand, a human rights activist and co-founder of the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for the Promotion of Human Rights and Democracy in Iran, Azadeh Pourzand, a human rights activist and founder of the Siamak Pourzand Foundation, Omid Shams, an IranWire contributor and PhD candidate in human rights at the University of Portsmouth, and Arash Azizi, a historian at New York University and a writer. IranWire founder Maziar Bahari chaired the discussion.

The main questions we wanted to explore: What is transitional justice and is there a recommended process for it? If so, what are its key components and principles?

1. Transitional justice means different things to different people

Gittleman defined transitional justice as “the processes and the responses that societies might have to recover from mass atrocities or mass violence or conflict or other serious human rights violations. The question that transitional justice seeks to answer is how do societies come together? How do they rebuild after extreme violence and trauma and harm?”

But there is no one-size-fits-all approach to transitional justice. Depending on the context, it may involve documenting and understanding past events, holding perpetrators to account, offering reparations and restitution to victims, taking steps to prevent future crimes, or reforming institutions which were complicit in past crimes. For some victims, finding out and publicizing the truth might be central, while other victims might be seeking formal prosecutions for perpetrators.

Ultimately, people might disagree about when justice has been achieved. For Gittleman, it is about matching personal demands and expectations with what is realistic and politically feasible.

Although transitional justice is always context-specific, there are general principles that can be helpful. Gittleman said, “You want to solemnly reflect on what has happened, find a way to restore victims and then find a peaceful future.”

As Gittleman explained, every context is unique and transitional justice is most effective when communities chart their own path. Justice is more likely to lead to the long term goal of rebuilding a society and preventing recurrence of crimes, “if victims feel like their demands are being adequately addressed – and they'll be adequately addressed if they are helping to determine what justice looks like.”

2. Preparing for justice starts now

One topic touched on by the panel was what “transitional justice” looks like before any “transition” has taken place.

In Iran the oppressive regime remains in power. Crimes are being committed in the present moment. But what work can be done? How can we start the conversation? And how can we prepare now for transitional justice in the future?

Azadeh Pourzand said Iran has a past, “but we haven't yet had the privilege of calling all of that the past because we still have a mass violator ruling the country. In a way, transitional justice seems like a luxurious beautiful future to imagine.” She added, “At the same time, we have to start the conversation somewhere.”

Gittleman responded that “even when the transition or evolution seems far away, there's still a lot of work that can be done to advance transitional justice.” Sometimes the work can start even if there hasn’t been a significant change or transition. This might involve documenting what is happening, fundraising and organizing.

She gave the example of Burma, where “even when there was no transition, even when the crimes were very much present ... civil society groups were still coming together to organize, to document and do all of that hard work that did help them years, years down the road.”

3. Victims have to become their own advocates

There is a weight on victims not only to know what they need, but then to advocate for it. While coming to terms with what has happened to them, they have to answer challenging questions about what justice means and what it looks like, such as what will enable healing for individuals or for a community? What is the most important thing here? And what is actually achievable?

Azadeh Pourzand described how even when trauma is very fresh for victims, they face the “burden of all these big concepts – rule of law, transitional justice, democracy” and are forced to become grassroots leaders overnight. Gittleman agreed there is an “inherent unfairness” to the hard work being placed on victims.

Bahari suggested that, as well as the ethical issues of putting victims and survivors in charge of the transitional justice process, it might not be practical either. “We are talking about certain procedures that ordinary people don't understand and don't know that much about.”

But working actively towards justice can be profoundly healing. Omid Shams emphasised how important it is for people to be heard and to come together with a mission to give them meaning, “not only in terms of healing the society, but also for the victims as well.”

This kind of work can give victims an agency which they have been denied. Ladan Boroumand agreed that it can turn “passive victims of an unspeakable crime” into “agents of history”, and “that changes their approach completely.”

“What dictatorships usually deny from people is empathy and agency,” Bahari said. “And what transitional justice does is that it allows two people to empathize with each other, and it gives victims agency.”

4. Justice is not the same thing as democracy

The panel discussed whether transitional justice is possible outside of a democracy, a particularly relevant question for Iranians pursuing justice in their own country.

While transitional justice is a necessary step towards democracy in a country, Bahari noted that democracy is not “a panacea” and “it's not going to solve all the problems”.

Gittleman suggested justice can be found even in countries that aren’t democracies, and equally democracy alone is no guarantee of justice. She gave the example of the democracy of the United States, noting that “we have had transitional justice efforts within the United States” and this hasn’t prevented the country’s “longstanding problems with racism and discrimination”.

In contrast, the African country of Chad, despite not being a democracy, is often considered a success case because of the way victim groups came together after the fall of President Hissène Habré in 1990. Their work resulted in Habré’s prosecution for human rights abuses twenty-five years later in 2015.

5. Justice takes time

Like the example in Chad shows, justice cannot be achieved overnight. Successful transitional justice demands a long-term and holistic perspective, and requires a lot of political will at every stage of the process.

“It's not always the immediate justice process or the procedures that are being followed… but it's what happens next,” Gittleman said. “It's really hard to keep the pressure on and the interest you have built up for so long.” She believes it’s important to have this long-term perspective to manage expectations and prepare people for the work required.

The justice process following the Holocaust has been decades long and is still ongoing. Redressing and reckoning with the Holocaust is a process that has spanned many decades and continues to this day. Given that the Holocaust affected millions of people in multiple countries, reconciliation is a transnational endeavor that involves various initiatives in several countries. Survivors of the Holocaust experienced processes of redress and reckoning differently; there was not a single common experience of post-Holocaust justice.

Boroumand said, “We need to conceive of transitional justice in a structural relation with political and judicial institutional reforms and on a long term basis.” She added that we need a holistic approach “if we are to plan the transition of justice for the future of Iran”.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments