The fact that Iran is rushing to execute even more of its citizens than usual under the watch of President Hassan Rouhani inevitably gives rise in the Western media to questions about his reliability as a partner in nuclear diplomacy. Does the fact that people are being executed at rate of five human beings per week mean that Rouhani is more or less poised to deliver on the promises made in Geneva? Is he deftly giving the hardliners room so that he is empowered on the diplomatic front, or is he vulnerable before a violent campaign that seeks to undermine those same ambitions?

To Iranians living in the shadow of public executions, these are hardly the most pressing questions. For those who live in towns or areas where drug smugglers are hung by cranes, for those who later see such images on news websites or the morning papers, there are other concerns, such as why the state wants us to watch, why some oblige, and what that watching does to us as a society.

When judiciary officials preside over public executions, they claim Iranians support such spectacles as a means of deterrence. The parents who take their children to watch hangings can only have this in mind, unaware that rather than imparting a lesson they are inflicting profound psychological harm. The civic activist Kaveh Ahangari recalls witnessing a public execution where children were present. He had not planned to attend, but found himself passing near a square where authorities were executing five men. He tried to hurry past though he admits to being curious as to what the men had done. “They're murderers and rapists,” people said. But for Ahangari, the worst part was seeing parents hoist their children above their shoulders to give them a better view. “They must know this is not a circus or a puppet show, what is this going to do to a child's spirit?” he says.

Cultures of violence are partly cultivated by states, such as the United States of America, which permits society liberal access to guns and stomachs the killing that ensues. But in some cases they result from a collusion between state and society itself; the Islamic Republic, for example, energetically applies the death penalty and desensitizes its citizens to violence by conducting executions in public. But deep-seated cultural tendencies such as a high tolerance for domestic abuse create fertile ground for state-sanctioned violence. The state, in a way, is an extreme and grotesque extension of society's worst characteristics, legitimizing violence rather than mandating laws against it.

For an Iranian middle class that is consuming more popular psychology than ever before and eagerly embracing the parental over-attentiveness that is now endemic in the West, the state's promotion of violence in public space raises deep concerns about how to protect children from witnessing or hearing about public executions. “Being exposed to violence, even something like an auto accident, can have lasting traumatic effects on psyche and ability to function,” says Payam Akhavan, a prominent human rights lawyer who has worked extensively on Iran. “A child that witnesses not just an accident but an act of deliberate violence sanctioned by the government becomes deeply scarred, an abnormal child.”

The question that arises for many is whether there is also psychological fallout for those who hear and watch from a distance. Children who overhear reports on the news, catch glimpses of photos in newspapers, hear from passersby about a nearby execution. Though they do not witness the killing directly, it enters their consciousness as something that happens in their town and community, something that is tolerated and enacted by the same government that appoints the local traffic cop and registers baby names. “We have to understand that cumulative exposure to violence creates emotionally dysfunctional people, and earlier the exposure the more profound that trauma will be,” says Akhavan.

For children, the worry is that witnessing violence will create lasting trauma, but for adults, mental health practitioners say, the concern is that violence is more easily enacted at home, in people's living rooms. Shahla Ezazi, a professor at Alamah Tabatabai University whose researches domestic violence, says that public, state-sanctioned violence has a desensitizing effect that aggravates abuse in the home. “Rather than showing violence to be vile, the state uses violence to further its own goals, and this intensifies the cycle of violence in society.”

But while the cultural fallout of public violence seems self-evident, some argue that it is problematic to draw societal conclusions about spectators themselves. That those who attend hangings are ordinary citizens caught up in a frenzied moment, and do not reflect anything exceptional about Iranian society. “What can we expect from the masses? When there's an execution being held in public, it inevitably inflames people,” says the activist Mazdak Abdipour. “Even here in Europe if there was to be a scene of great violence in public, people would be drawn to watch.”

Abdipour says he once attended a public hanging in Iran. “I saw people pressing forward, I saw the corpse hanging afterward,” he says. “But I couldn't bring myself to watch the moment of death.”

The problem in Iran, he believes is that the state and media have colluded to smother society's collective conscience, leading to an ethical impunity between Iranians that is also on display in individual, daily interactions.

He cites a now widely discussed killing in 2010, when a man killed his wife's lover in north Tehran's Taj Square, in the neighborhood of Saadat Abad. One or two people on the scene tried unsuccessfully to intervene, but the majority of passersby gathered around to watch and film the attack on their mobile phone cameras. The wounded man was finally transported nearly 30 minutes after the attack to a hospital and died shortly later.

What public executions have done in Iran is to push capital punishment into the public eye, as a drawn out spectacle of anguish that citizens are meant to take lessons from, perhaps in avoiding a life of crime, perhaps in blind obedience. While it may well be that most Iranians support capital punishment, there is little space for debate about that question while authorities are conducting hangings in public squares. Iranians must first think about, and perhaps one day organize collectively around, whether they oppose the medieval practice of public killing, and then only later consider what they think about capital punishment itself.

* * * * * * * *

Starting today and continuing throughout the week, IranWire is publishing a collection of articles and films that deal with public executions and Iran's application of the death penalty.

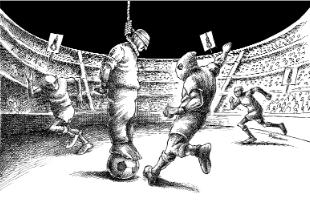

On Monday, we begin with the piece above, which explores the psychological damage and social fragmentation that is wrought by public hangings. A second piece uses interviews with several Iranians who have watched executions to examine people's disparate motivations for attendance and the lingering pain of having borne witness. We also debut on Monday the short film clip “The End of Iran,” contributed by an Iranian inside the country that sets disturbing images of large crowds gathered before hanging to The Doors' The End and darkly raises the question of whether the damage that has been done by such encounters is now irreparable, a part of who we have come to be as Iranians.

Tuesday will feature an extended report by Mahrokh Gholamhosseinpour on Iran's track record of executing minors, and what executed children's family's say is a culture of judicial laxness in investigating crimes that involve the underage. We also include another film clip from Iran, “Morning Circus,” which challenges the conventional reasons Iranians who attend executions offer – from instilling deterrence in children, to wishing to see justice enacted – by setting their attendance to circus music and suggesting they are motivated by a near sadistic prurience.

Wednesday sees the inclusion of a piece by Emadden Baghi, a longtime reformist activist, on his decade-long reflections on prisoner's rights when condemned to death, along with “Along Came a Spider,” Maziar Bahari's remarkable 2002 documentary on the serial killer Saeed Hanaei, who killed 16 prostitutes in Mashad because he was convinced Islamic justice legitimized their deaths.

On Thursday, Confessions of a Hanging Judge powerfully recounts the experiences of a death row judge who meted out execution sentences despite deep reservations, and ultimately retired from his work under the strain.

Friday we end with an extended piece by Mohammad Mostafaei, a prominent Iranian defense lawyer who had handled numerous death row cases and discusses the challenges of defending clients up against such a grave sentence.

Why Would You Attend a Hanging?

Put Death Penalty to a Referendum: an Interview with Emadeddin Baghi

"Since I resigned, I sleep better.”

The Value of Human Life: An Interview With Mohammad Mostafaei

The Most Disadvantaged Groups at Risk of Execution

Mohammad Mostafaei’s 10 Steps For Abolishing The Death Penalty

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments