Holocaust Memorial Day takes place on 27 January each year. It’s a time to remember six-million Jewish people and millions of other people who were killed by the Nazi regime and its allies. For this reason, we are re-publishing a number of articles on Iran and the Holocaust on IranWire. This article was originally published in May 2016.

***

Claude Morady is an antique jewelry dealer in Los Angeles. One strange day in 2003, he got a call from a scholar in Vermont, asking about his father. “This gentleman calls and says, ‘This is Fariborz Mokhtari. Are you the son of Ibby Morady who helped save a few thousand people during the war?’ I go, ‘That's my dad, but he didn't do that.’” Mokhtari was researching the life of Abdol-Hossein Sardari, an Iranian diplomat who had served in occupied Paris during the Second World War, an investigation that would eventually form the basis of his book, In the Lion’s Shadow. Mokhtari was convinced he had found the right Morady family, and he was right. Claude’s father Ibrahim had been friends with Sardari in Paris, and together they had hatched a successful plot to fool the Nazis and protect Iranian Jews, and possibly Jews from other countries, in France.

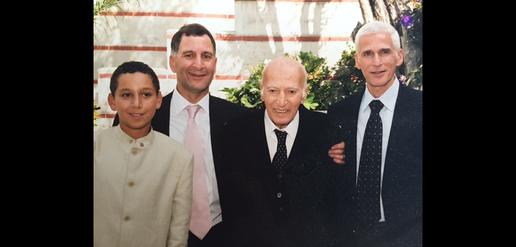

The next few days brought a whirlwind of revelation. “It's funny,” Claude says. “My father, rest his soul, lived to be 95. He never told us anything about anything. He was a very modest guy.” Soon, Mokhtari came to visit, and, with the help of the Moradys’ family friend George Haroonian, a Los Angeles-based carpet dealer and community activist, interviewed Ibrahim in depth. “Then a week and half later, it's Yom Hashoah -- Holocaust Remembrance Day -- and we go to the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, our big Holocaust Museum here in LA, and there are 700 people. My Dad gets up with Sardari's nephew and they honor both of them. I never knew any of this had happened! Amazing! Just like that!”

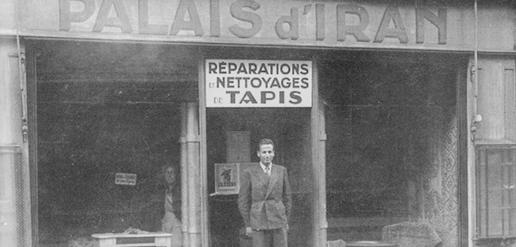

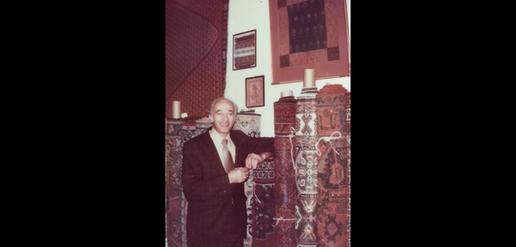

Before moving to the United States in 1952, Ibrahim had worked in Paris as a carpet dealer. He had moved there with his father in 1920, and together they ran two Persian carpet stores near the Paris Opera House. “Paris was a mecca for Iranians at that time, and there were at least a few hundred Iranian Jews in France,” says Haroonian, who met Ibrahim through his own father’s work in the carpet trade. This, Haroonian says, was partly because of the influence of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a Paris-based Jewish organization that had provided education to Jewish Children in Iran and other Middle Eastern countries.

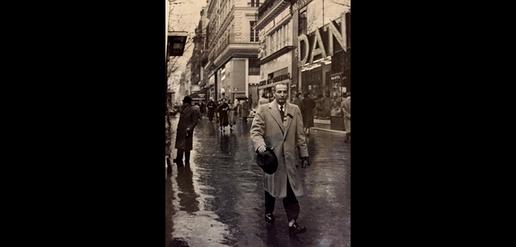

Ibrahim, a gregarious man by all accounts, had a great life as a young man in Paris in the 1930s. But in 1940, Germany invaded France, dividing it into an occupied north, and a compliant but nominally sovereign French state in the south, with its capital in Vichy. The Nazis imposed their racial laws across the country, and French authorities demanded that all Jews register with the police. While Iran and Germany had a diplomatic agreement protecting Iranian citizens in Europe, Ibrahim knew his family -- his three brothers and three sisters -- were at risk. “They were in trouble,” his son, Claude says. “The Gestapo would turn up at their house. They had to leave their doors open, and the Gestapo would just walk in. A few times my dad was going to get grabbed. He mentioned that there were some close calls.”

The Gestapo built a network of informants in France, creating a spectacle of treachery that Ibrahim, then in his mid-twenties, would never forget. “He was just so disillusioned when he saw people lying and turning in their friends for money,” Claude says. “The Germans would pay people to turn in their neighbors. He ended up so disappointed with the French.” But the Iranian community in Paris was more close-knit, and Ibrahim, being a prominent merchant, was especially well connected. Among his friends was Abdol-Hossein Sardari, a young Iranian diplomat in his twenties, who had been left in charge of the Iranian legation’s consular office -- and a safe full of blank passports -- when Ambassador Anoshiravan Sepahbody had fled for Vichy.

When Ibrahim learned that Sardari had been ordered to return to Iran, he implored him to stay. Sardari, already troubled by the orders, agreed. “My dad knew Sardari had these papers and passports, and had the ability to write fake papers and make fake passports to help people,” Claude says. Ibrahim, Sardari, and four friendly Iranian businessmen held a secret meeting at Ibrahim’s rug store. “My dad said, ‘Let's pool our own money, and make all these papers up.’” They drew up a list of Iranian Jewish families, and prepared documents for them. Claude discovered late in life that his father had kept some of these papers. “My father never told us about this, but we have some classic family albums, and one of them has some of these papers in them. He saved lots of things, thank God.”

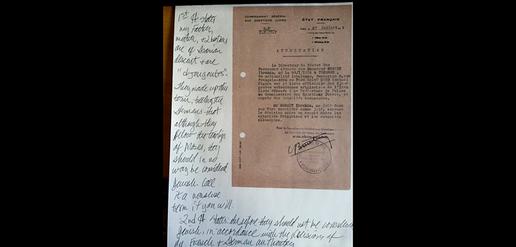

Sardari got around Nazi race laws by drawing on his skills as a lawyer to present a historical-theological premise that would confound the Nazi conception of race. Sardari argued that Iranian Jews were not really Jews but members of an arcane minority called Djougoutes. “Call it a nonsense term,” Claude says. “They told the Germans that although the Djougoutes follow the teachings of Moses, they should in no way be considered Jewish.” He then prepared official documents identifying Iranian Jews, as well as some non-Iranians, as members of the minority. Haroonian has a theory about where the term came from. “In Farsi the derogatory word that is used by non-Jews is ‘Juhud,’” he says. “The Germans say ‘Juden.’ So he made it ‘Djougouten.’”

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC identifies Djougoutes, or “Jugutis” in English, as descendants of Persian Jews forced to convert to Islam in 1838, who continued to observe Judaism privately. “Sardari argued that the Jugutis should not be considered racially Jewish,” says Susan Bachrach of the Holocaust Museum. “He reported that they were a largely assimilated minority whose members frequently intermarried with non-Jews and spoke [Persian], and that Jugutis had ‘all the civil, legal, and military rights and responsibilities as Muslims.’”

In any case, the ruse bought perhaps more than two thousand people protection throughout the war. While the Nazis debated Sardari’s novel theory among themselves (Adolf Eichmann, one of the chief organizers of the Holocaust, dismissed them as early as 1942), Sardari launched an eloquent campaign of subterfuge on the Djougoutes’ behalf, creating enough confusion to protect Iranian Jews from anti-Jewish measures, and effectively allowing Iranian Jews in France to run out the Nazi clock.

For Sardari it was all a matter of duty. “The most important thing I can tell you,” Haroonian says, “is that the Iranian Jews of Paris invited Mr. Sardari so that they could thank him.” This was in 1947. “They wanted to say that they appreciated what he did, and that they wanted to prepare the silver plates and this and that. He said, ‘I just did what I was supposed to do.’”

The Morady family was able to stay below the Nazis’ radar throughout the war. Neither Claude nor Haroonian knows whether Ibrahim stayed in touch with his old friend. When Sardari returned to Iran, he faced accusations of misconduct over his wartime actions, though he later cleared his name. He emigrated to England and died in Nottingham in 1981. Ibrahim died in 2006. Claude wishes he had asked his father more. “There were so many things that I wanted to know about my dad that he never told me. My advice is talk to your parents, get as much information as you can, because they are walking history.”

But at the very least, Fariborz Mokhtari has preserved the story of Ibrahim’s fateful friendship with Sardari in his 2011 book, In the Lion's Shadow. Now that Iran is synonymous for many outsiders with Holocaust denial, Haroonian thinks it’s a story more people -- Iranian and non-Iranian -- should know about. “Iran has two faces,” he says. “On the one hand, Iranians are very hospitable, friendly, kind people, and on the other hand, there is this idea that whoever is not like us is not good. People like Sardari, who was not told too much about Jews, just knew that they were the same people, that they speak the same language and they belong to the same land, so he treated them kindly.”

Also in this series:

Menashe Ezrapour: The Iranian Who Survived the Nazi Work Camps

From Krakow to Tehran to Jerusalem: One Jewish Family's Story

Read more about Iran and the Holocaust:

Ibrahim Morady: The Carpet Dealer who Helped Fool the Nazis

Sardari, the Iranian Muslim Who Saved Jews from the Holocaust

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments