Farrokhru Parsa was a doctor, an educator, a women’s rights activist and the first female cabinet minister in Iran, an achievement for which she was executed by the Islamic Republic.

Fakhr Afagh Parsa, a women’s rights activist and the editor of Women’s World magazine, gave birth to Farrokhru in Qom in February 1922. At the time she was living in exile, punished for writing an article that defended gender equality in education. The article sparked protests from the clergy.

Farrokhru Parsa's father, Farrokhdin Parsa, worked at the Ministry of Commerce and was the editor of two magazines about industry and commerce.

Shortly after Farrokhru’s birth, her mother was released from exile with the help of Mirza Hassan Khan Mostofi, the prime minister at the time, and the family returned to Tehran.

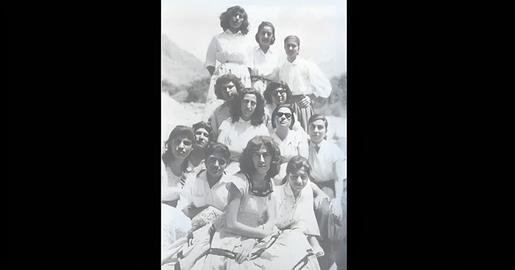

Farrokhru Parsa received her high school diploma from the Junior Teacher’s College in Tehran and, when she was 20, a degree in biology from the Senior Teacher’s College. She then studied medicine at the University of Tehran. Farrokhru Parsa received her medical degree in 1950 and continued her studies in the field of children and newly-born babies. While at university, she also had a keen interest in culture. Together with her colleagues, she founded the Women of Culture Society in 1954.

Both during her medical studies and after receiving her medical degree, Farrokhru taught biology at Tehran high schools, including Jeanne d'Arc School, a French institution for girls founded by Catholic missionaries in 1900. One of her students at this school was Farah Diba who would later marry Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi.

Six years after she started teaching at Jeanne d'Arc School, Farrokhru was appointed as the principal of the girls’ Valiollah Nasr High School. A year later, in 1957, she was chosen as the principal of Noorbakhsh High School and remained at this job until she was elected to the parliament. She said that when she took over the management of this school it had only 110 students but when she left 1,850 girls were studying at Noorbakhsh High School.

In 1960, when the National University of Iran (renamed Shahid Beheshti University by the Islamic Republic) was founded, Farrokhru Parsa was appointed as its secretary-general. She was the first woman in the history of Iran to occupy such a high position in the field of education.

In 1963, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi decided to launch a “White Revolution” and a referendum was held. For the first time, women were allowed to vote.

“When I heard that there was going to be a referendum, I said to myself that women must also participate in this referendum,” she said. “Every day, with a group of women, we went everywhere to get women the right to vote in the referendum.”

In the same year, she was elected to the parliament and became very active in pushing legislation to amend existing laws concerning women and family, something that aroused the enmity of the hardline clergy.

In 1965 Farrokhru Parsa was appointed as deputy education minister and, in 1968, Prime Minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda picked her as education minister. She became the first woman in Iran to become a member of the cabinet.

“I want to put great responsibility on a mother’s shoulder,” Abbas Hoveyda told her. ”I want to put the task of educating the country’s children in a mother’s hand. I want our minister of education to consider other people’s children as her own.”

According to her friends and relatives, Farrokhru Parsa’s only two concerns in life were her family and her struggle for gender equality.

Writing about schoolgirl uniforms, Parsa wrote: “They’re not allowed to wear anything except school uniforms, whether it be the chador or a miniskirt.” She said she wanted to separate “education and progress” from “outfits.” Even Hoveyda’s critics believe that she played a significant role in advancing education for girls in Iran.

Parsa also financially sponsored the Islamic Center in Hamburg. Its director was Seyed Mohammad Beheshti, the first chairman of Iran’s Supreme Court following the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Beheshti was assassinated on June 28, 1981.

Before the revolution, Beheshti and Mohammad Javad Bahonar, the second post-revolutionary president, advised Parsa on how to compile school textbooks. Under Parsa, Bahonar secured a permit to open several religious schools in Tehran.

Following the revolution, Parsa stayed in Iran, and lived in hiding for some time. According to Kayhan Newspaper, she was arrested on February 16, 1979, at her son’s house in Farmanieh district, together with her husband, General Ahmad Shirin Sokhan. At the time, she believed her innocence would be proven during what she was told would be a “fair” trial.

But upon entering the courtroom in a gray uniform and wearing a headscarf, those in the audience booed and cursed her. Her response was: “I believe in the justice of my country.”

Her trial lasted nine sessions. The judge overseeing the case, Sadeq Khalkhali, known as the “Hanging Judge,” sentenced her to death and confiscated her property. She was charged with “wasting and plundering public properties, propagating corruption and prostitution in the domain of culture, appointing pervert individuals to important ministry positions, organizing mixed outdoor camps and violating Islamic morality.”

Parsa rejected the charges of being a Baha’i, having an illegitimate relationship and cooperating with Savak, the Shah’s secret service.

In her last message from her prison cell, Farrokhru Parsa addressed her children: “I am a doctor so I have no fear of death. Death is only a moment and no more. I am prepared to receive death with open arms rather than live in shame by being forced to be veiled. I am not going to bow to those who expect me to express regret for 50 years of efforts for equality between men and women. I am not prepared to wear the chador and step back in history.”

On May 8, 1980, the prosecutor-general of the Islamic Revolutionary Court announced that Farokhru Parsa had been hanged.

The following day, her body was buried at Tehran’s Behesht Zahra Cemetery but, a short while later, her grave was leveled by bulldozers. When her children put another gravestone with the word “Mother” inscribed, the bulldozers came once again and, this time, nobody could find her last resting place.

In his book Mrs. Minister, Mansoureh Pirnia gives a detailed account of Parsa’s final minutes: “They put her in a sack, wrapped ropes around her and dragged her to the gallows. The ropes were torn. Once she regained consciousness, she was once again taken to the gallows, but this time they wrapped wires around her. Apparently, she hadn’t died the second time either. The three holes in the dead body of one of the most influential Iranian women is a testimony of her most painful death.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments